Residents of the Slocan Valley town of Krestova, B.C., want pulp mill waste that's been trucked onto three properties to be removed over fears their ground water could be contaminated.

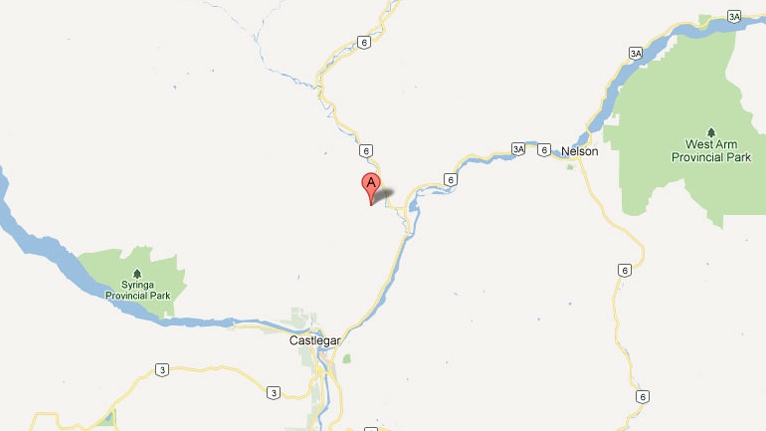

The Zellstoff Celgar pulp mill in neighbouring Castlegar is offering the so-called bio solids, which are created from wood waste, for free as a type of fertilizer that would otherwise be burned.

"I feel we're just being used as a dump site," said Nick Kootnikoff, whose well supplies water for eight properties and is within the 30-metre legal limit of an acreage containing the waste.

"If I knew what was in there I'd feel more comfortable, but from what I've heard it has sewage sludge in it," he said. "I'm uncomfortable with sludge that has human waste in it."

"We want it removed," said Alan Anton, who lives a few houses down from one property where the waste has gone. "There is a community hall and day care centre downhill of this field. If our water got contaminated that is our only water source and we're hooped for 25 years."

Anton said there are three properties containing bio solids in the community of 150 people that was settled by Doukhobors and is about 20 kilometres from Nelson.

Jim McLaren, a retired Celgar employee who now arranges the distribution of bio solids for the company, said the material contains mainly wood fibres, mixed with 40 per cent surplus bacteria, which aid in breaking down the wood fibres, and 10 per cent lime, grit, gravel and waste water.

McLaren said waste water from the sewage treatment plant is deposited on piles of bio solids and it's so safe that it's also dumped in the Columbia River.

He said Celgar delivers the fertilizer-like bio solids to property owners after a lengthy application process with the Environment Ministry.

"We don't think there is a biological risk to this material," said McLaren, who doesn't recommend people use the bio solids on land where food is grown.

He said 33 other properties in the Kootenay area contain the bio waste and that 27 applications for the material are pending with the Environment Ministry.

Krestova resident Joyce Van Bynen, who had 200 tonnes of bio solids applied to two acres in May, is sold on the product and said it helped revive her horse pasture within a short time.

The soil in the town is mainly sandy with little moisture retention and grows nothing but knapweed in the pastures. Van Bynen said that within two months of spreading the bio solids and grass seed, she has about 10 centimetres of lush grass for her horses to eat.

"There is nothing but good from this product. It's been tested seven ways from Sunday and has been proven to enhance the soil," said Van Bynen, who also works for Celgar, as an environmental technologist.

The bio solids are within six metres of her well and Van Bynen said she drinks from the same aquifer as the rest of the community.

"I am quite confident with what is in this material and that it is benign," she said, adding the bio solids have also been dumped on another property two kilometres from her own.

Before the bio solids are applied, the Environment Ministry requires Celgar to test the land and the bio solids for moisture content, trace metals such as arsenic, lead and mercury. It also tests for pathogens.

Chris Stroich of the Environment Ministry said there is no sewage sludge in the Celgar bio solids.

Trace metal values for bio solids delivered to Krestova "have been well below that specified in the ministry's (Soil Amendment Code of Practice)," he said in an email.

However, Walter Popoff, regional director of Area H for the central Kootenay district, said "Krestova residents are right to be concerned. Basically, the residents are concerned for their health."

The (Environment Ministry) tests that are done, in their opinion, are not sufficient enough to make them feel safe," he said. "If this was being done beside me, this would be my concern also and I would want reassurance."

"No amount (of bio solids) is safe as far as I'm concerned," Kootnikoff said. "If it is so safe, why doesn't Celgar bag and sell it?"

Popoff will be meeting with the Environment Ministry later this month to discuss the issue.

Krestova residents concerned about their health have the backing of Maureen Reilly, a director for the Ontario group Sludge Watch, which was involved in the Walkerton inquiry into the tainted water tragedy in 2000 that killed seven people.

Reilly is helping the B.C. residents research their concerns and said bio solids from pulp mills can be laced with chemicals and disease-causing bacteria.

"Beware of industrial mules bearing gifts," said Reilly, who called the bio solids a "waste product dodge" by pulp companies.

"I'm pretty familiar with what is in these wastes and have seen people who have become life-long ill from exposure to pulp mill sludge," she said. "I think the mill needs to find better ways to deal with its waste."

Krestova residents have dealt with bio solids concerns before, in 1996, when the material was applied to Van Bynen's property, which at the time was owned by another Celgar employee.

While the company had conducted a public consultation, the community appealed the decision to the Environmental Appeal Board, which dismissed the effort because the appeal wasn't filed within a 30-day time period.

The Environment Ministry did not notify Krestova residents before the bio solids were dumped on Van Bynen's property, despite assurances that would happen, say members of the community.

They didn't know the bio solids were coming until they saw the dump trucks loaded with the black, smelly compost-like material drive by their homes in early May, Kootnikoff said.