VANCOUVER -- Thirty-two years ago, a petite woman with blue eyes and brown frizzy hair packed all she could fit inside a suitcase and set off to find a haven after being kicked out of a low-rent Vancouver apartment building in the middle of the night.

She didn't get far. Kristin Gurholt's body, naked with her skull fractured, was found nearby in a dirty alleyway on Sept. 4, 1981. Police have never made an arrest.

Moving details of Gurholt's 34-year life and her ghastly death, some never revealed publicly before, are now posted on a new website that the Vancouver Police Department hopes will shut the file. It joins seven other historic murders, found at vpdcoldcases.ca, that remain shrouded in mystery while family members still look for answers.

"For them, the memories of the sweet little girl who filled their house with music have been forever tainted," says the case overview for Gurholt, describing the woman who grew up in Dartmouth, N.S., where she loved to read and play piano.

Without justice, the site says, the family holds only "the painful knowledge of how her life ended and the fact that no one has been held accountable."

The website was launched Tuesday as an additional effort by the force to crack 113 unsolved homicides that have stacked up over the past 40 years. The eight cases online span between 1981 and 2008, while the force plans to add more over time.

"We just want to breathe some life back into these cases," Deputy Chief Adam Palmer told reporters, explaining he hopes the clickable files, maps and photographs refresh memories.

"Get them to recall things they may have been uncomfortable talking about at the time -- either witnesses who may have seen something or heard something ... but now with the passage of time, they realize they may not be in any peril or it may be the time to step forward and do the right thing."

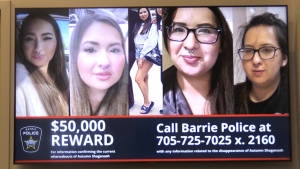

The other cases involve six women and two men, and include details about the death of 61-year-old Cathy Berard, who was assaulted and left on the grounds of an east Vancouver high school in 1996. Another reveals that an anonymous letter was sent to police confessing to the killing of Danielle Larue in 2002. Her body has never been found.

Families of the victims support the website approach, said Palmer, which the force believes could garner tips from a large public audience. Often a small lead, perhaps chatter along the grapevine, could be all that's necessary to re-activate a case, he said.

"Armchair detectives" are encouraged to scroll through the files, he said.

"We're happy to hear from people, as well, if they have any information or leads or theories or anything that comes to light that they may dig up. Any information is good."

The concept already exists. The Toronto Police Service and national RCMP also post cases, as do many forces in the U.S., though most are not nearly as interactive or visually appealing as the site that cost the Vancouver force less than $10,000.

The San Diego Police Department began posting its cold case homicide information online within the past 10 years as a supplement to other lead generators like Crime Stoppers, said Det. Sgt. Frank Hoerman.

The 32-year police veteran, who keeps track of the historic files, said the force does receive tips from the site. Every year his team closes a couple among the thousand-or-so unsolved cases dating back to the late 1800s.

He believes the Internet's vast reach, along with other technological advances like DNA testing, are driving new momentum in solving crime.

"They've gone cold for a reason, either for a lack of evidence or a lack of information," Hoerman said. "The most daunting issue is just looking for that one piece of physical evidence, witness evidence or some other type of information that can move the investigation forward."

But whether high-tech methods or good old fashioned sleuthing is involved doesn't really matter, so long as the job gets done.

"They feel very successful. Because they are so few and far in between," Hoerman said of investigators. "(But) the bigger issue is for the families of the victims, getting closure.

"That's what it really comes down to."