Sanctuary and torment: The complex history of Riverview Hospital

Content warning: Some of the details in this story are disturbing.

Set on the slopes overlooking the Coquitlam River, the psychiatric institution still widely known as Riverview was established to treat British Columbians with the most severe mental illnesses in a relaxing setting.

In the end, it would prove to be both a sanctuary and a place of torment for its patients.

The complex history of the site spans more than 100 years, and is casting a long shadow over the future planning for the site, which was quietly halted earlier this year.

What was originally called The Hospital for the Mind on Mount Coquitlam was named Essondale when it fully opened in 1913, and initially housed only men. Women were later included and all patients were compelled to undertake manual labour described as “occupational therapy,” which purportedly helped manage their symptoms but also supported the facility’s operations and financial position, according to a history compiled by the City of Coquitlam.

The grounds were intended as a therapeutic sanctuary and the calm, pastoral setting provided respite and relief for some patients, with the population steadily growing over the years. Many lived their entire life there.

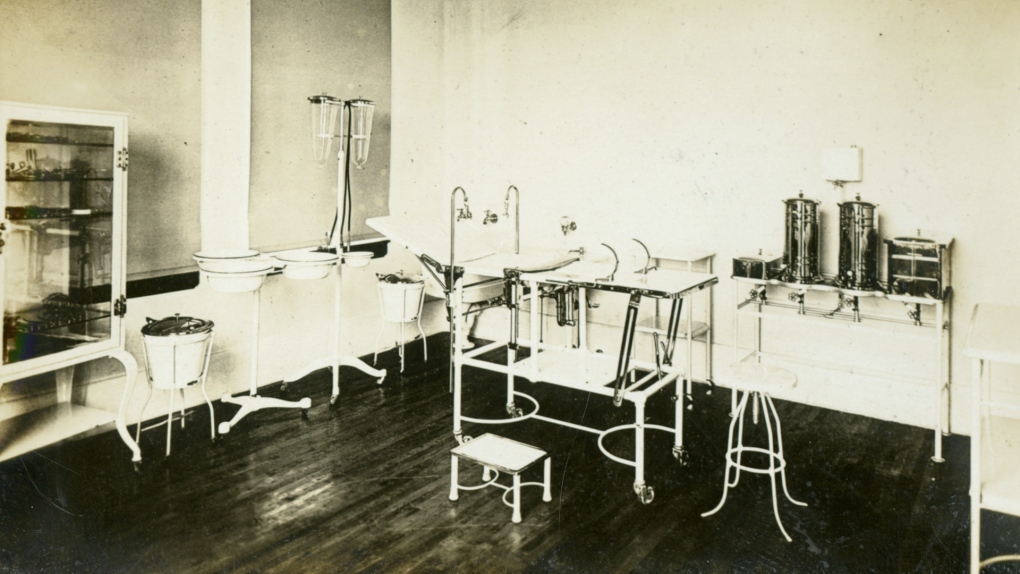

Some patients were subjected to treatments and therapies unconscionable by today’s medical standards: shock therapy, insulin-induced comars, and “hydrotherapy” that included hours exposed to or blasted with hot or cold water. Hundreds of patients were sterilized against their will and were awarded compensation decades later.

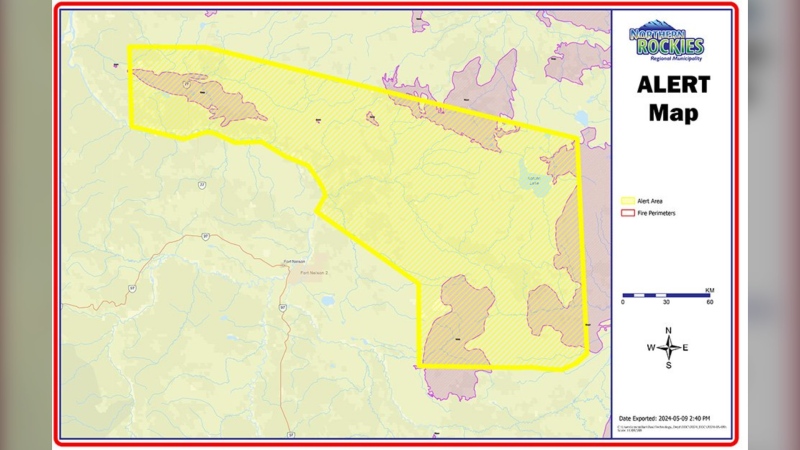

(City of Coquitlam)

(City of Coquitlam)

“Many people who were detained at Riverview in the past identify as survivors – they were there against their will and they were not allowed to leave,” said Laura Johnston, legal director of Health Justice. “Riverview used mechanical and chemical restraints and many other practices that were considered controversial and criticized even at the time they were being used.”

A post-war surge driven by traumatized soldiers saw a peak population of approximately 4,700 resident patients by the 1950s.

A NEW NAME AND OUTLOOK

Advances in understanding of mental illness and breakthroughs in pharmacology saw a massive shift in the facility’s approach: psychotherapy and powerful anti-psychotic drugs saw the first wave of patients sent to live their lives as they wished.

“We have discharged more patients to the community than ever before; public understanding and acceptance of mental illness is improving,” wrote Medical Director F.E. McNair in March of 1956.

By 1965, the recreational facilities were set up for patients, they were allowed to visit friends and family, and the facility was renamed again: it was now Riverview Hospital.

(City of Coquitlam)

(City of Coquitlam)

“(Up to then) they were treated horrid, horrible, the people who were mentally ill,” said veteran journalist and historian, Mike McCardell. “But by the 1970s when I got to know it really well, there was kindness, love, understanding at Riverview. There were baseball teams – I played on one!” https://www.facebook.com/MikeMcCardellCTV/

The first building closed permanently on the site in the 1970s as the population continued to decline and more people went for housing and treatment, but ultimately left. This challenges the common perception the hospital was rapidly emptied in the 1990s alone, but also foreshadowed future issues.

“There’s been several waves of transferring people out of Riverview,” said Marina Morrow, a York University professor who studied B.C.’s mental health landscape in her years teaching at Simon Fraser University. “In the ‘70s when people left Riverview, we didn’t have community-based mental services yet. There wasn’t infrastructure like that in Canada.”

THE FULL CLOSURE OF RIVERVIEW

By the 1980s, the hospital was actively being downsized for two reasons: a belief patients belonged in community rather than warehoused and out of sight, and the government deciding it was financially better as well.

“Government policy at the time was to have psychiatric services developed in the acute care hospitals like Vancouver General and St. Paul’s (hospitals),” said Dr. John Higenbottam, a clinical professor of psychiatry at UBC who was vice president of clinical programs at Riverview Hospital from 1980 to 1992.

He described orders from the then-NDP government in Victoria where “they actually gave the hospital quotas on the numbers of patients to discharge to the community, so it didn’t matter what they’re needs were – basically, get ’em out.”

Both Higenbottam and Morrow said there were insufficient supports at the time, backed up by a 1994 Ombudsman’s office report noting “transition issues around discharge planning.”

Increasingly, many of those people wound up on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where accommodation was cheap and patients were often preyed upon by drug dealers.

(City of Coquitlam)

(City of Coquitlam)

“I saw it hundreds and hundreds of times,” said McCardell. “The government said ‘We have all these places set up for them.’ They lied. They didn’t have all these places set up for them.”

Despite that, plans continued to wind down the hospital and discharge patients through the 1990s, and the BC Liberals carried on closure plans when they came into power. Morrow tracked bed-to-bed transfers of the final wave of patients to other facilities leading to Riverview’s full closure in 2012.

While the province has been providing some supportive housing options for those who no longer need in-patient care, it hasn’t been enough and some patients continue to find themselves in a loop of involuntary treatment to discharge and back again.

The medical consensus is supportive housing, rather than long-term or permanent institutionalization.

“That shouldn’t be someone’s home,” emphasized Higenbottam.

The history of the Riverview lands began much earlier than the well-known psychiatric hospital. The Kwikwetlem First Nation’s stories and legacy at the site span thousands of years and will be the focus of Thursday’s instalment of our Riverview: In Focus series.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Prince William says wife Kate is 'doing well'

Prince William said on Friday his wife Kate was 'doing well' in a rare public comment about the Princess of Wales as she undergoes preventative chemotherapy for cancer.

BREAKING Toronto mayor hints that WNBA team is coming to the city, marking the first franchise in Canada

Toronto Mayor Olivia Chow says that she is hopeful an announcement could be made soon amid multiple reports that a WNBA team is coming to Toronto in 2026.

Magnitude 4.2 earthquake reported off Vancouver Island's west coast

A 4.2-magnitude earthquake was recorded west of Vancouver Island early Friday morning.

Ontario coroner to investigate death of man who suffered cardiac arrest while waiting in ER

A provincial coroner will be investigating the death of 68-year-old David Lippert, who suffered a cardiac arrest while waiting in a crowded emergency room in Kitchener, Ont.

Average hourly wage in Canada now $34.95: StatCan

Average hourly wages among Canadian employees rose to $34.95 on a year-over-year basis in April, a 4.7 per cent increase, according to a Statistics Canada report released Friday morning.

This iconic Canadian song is turning 50

Andy Kim's 'Rock Me Gently' is marking a major milestone, as it celebrates its 50th anniversary.

From outer space? Sask. farmers baffled after discovering strange wreckage in field

A family of fifth generation farmers from Ituna, Sask. are trying to find answers after discovering several strange objects lying on their land.

Federal government bans watercraft from Manitoba lake popular with tourists

The threat of zebra mussels has prompted the federal government to temporarily ban watercraft from a Manitoba lake popular with tourists.

Her SUV was stolen in Montreal. A Good Samaritan on Facebook helped her get it back

Just as she had feared, a restaurant owner from eastern Quebec who visited Montreal had her SUV stolen, but says it was all thanks to the kindness of strangers on the internet — not the police — that she got it back.