Record number of B.C. black bears killed by officers in 2023 – as calls to conservation reached all-time high

B.C. saw the highest number of black bears killed by conservation officers in a single year in 2023, leading experts and advocates to call for more action from communities.

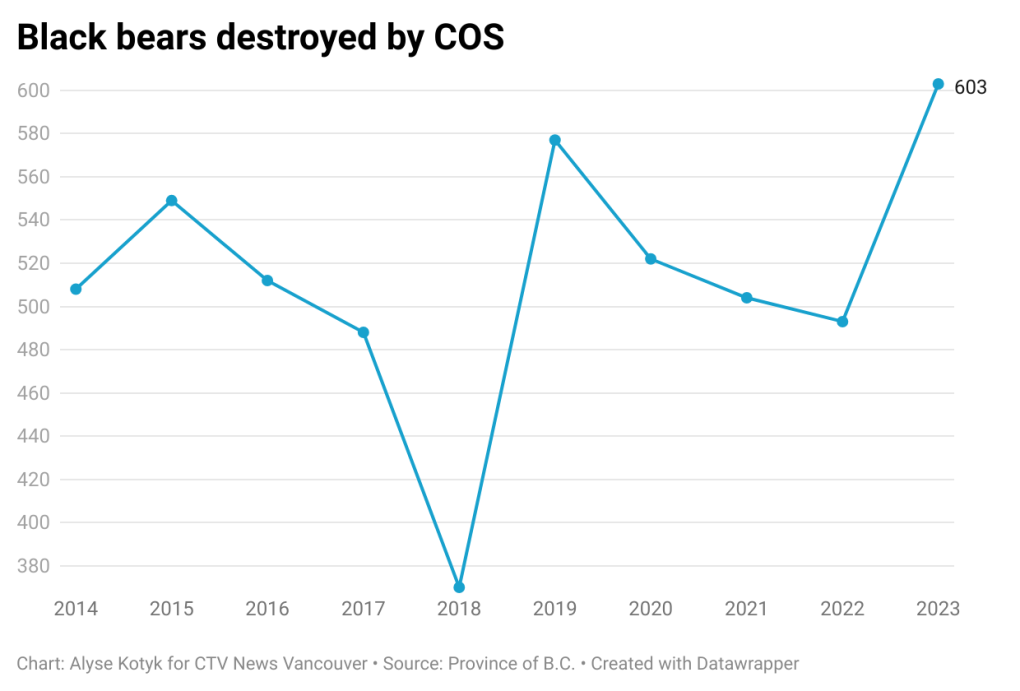

A total of 603 black bears were destroyed by members of the provincial Conservation Officer Service last year, up 22 per cent from 2022's total of 493, provincial data shows.

"It was a tough year to be a black bear in British Columbia," Holly Reisner, co-executive director of North Shore Black Bear Society told CTV News Vancouver. "We're looking at numbers destroyed by conservation, but there are certainly a lot of bears that lost their lives to different things – and we know that one of the big factors, too, is wildfires."

More than 2.84 million hectares of forest and land burned in 2023, making that wildfire season the most destructive in B.C.'s history.

Len Butler, deputy chief of provincial operations for COS, told CTV News Vancouver about 20 bears had to be euthanized in the Thompson-Shuswap region because they were severely burned from wildfires in that area. He also explained wildfires can play a role in displacing bears, pushing them into communities that are less familiar with wildlife management.

"The wildfires are going to move the bears, possibly into many of the smaller rural towns," he said. "We can't deny some of that happens and when you start moving bears into populated areas, we know we're going to have issues, we're going to have more calls."

Reisner echoed these concerns, saying some of these communities may not have public outreach programs in place if they previously didn't have encounters with bears.

"The whole public awareness of how to co-exist with the animals can make such a huge difference for their welfare," she said, adding that a lack of education and awareness could lead to more human-wildlife conflict.

Number of black bears destroyed by COS.

Number of black bears destroyed by COS.

Rise in calls from public

While a historical wildfire season may have played a role in last year's record-breaking statistics, officials say that's not the whole story. They noted the increase in black bear deaths corresponded with a surge in black bear calls from the public.

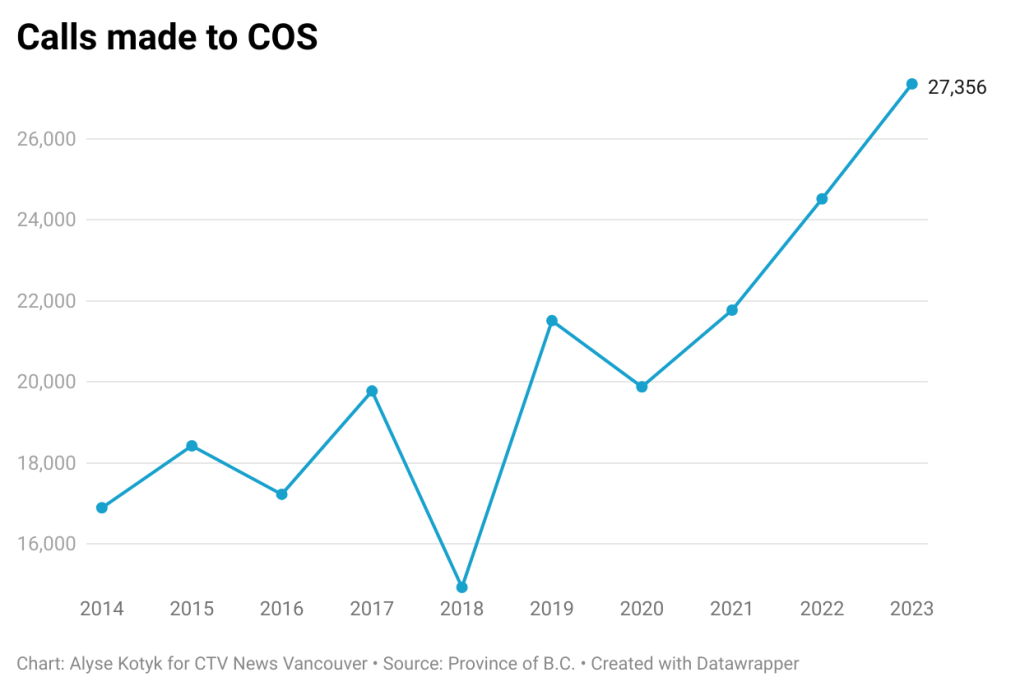

Reports to COS about black bears jumped by more than 2,800 year-over-year, continuing a trend the agency has seen over the last decade.

"There's no question the calls are going up. There's probably more people and … there's more black bears," Butler said. "That's always going to have an impact on our officers and probably lead to more contact with black bears."

Butler said the rise in calls is putting a significant amount of pressure on conservation officers, especially when their primary goals are enforcement and public safety.

"Working on these type of complaints … it takes away from the job of catching poachers and that's a challenge for all of us," he said. "Do officers enjoy destroying black bears? Absolutely not. They do not. But when it comes to public safety and that risk, that's our job. We have to make that risk assessment and do the best we can."

Provincial data shows calls to COS about black bears have risen dramatically over the past decade. Between 2014 and 2016, COS received an average of about 17,500 annually. But in the last three years, that average has risen to 24,500 annual calls.

Calls made to COS about black bears.Adam Ford, associate professor and Canada research chair in wildlife restoration ecology with the University of British Columbia, said there's a connection between the increase in calls and the rise in bears being destroyed. Ford explained the lethality of calls to COS has remained fairly steady in the last 10 years: between two and three per cent of them result in a black bear being destroyed.

Calls made to COS about black bears.Adam Ford, associate professor and Canada research chair in wildlife restoration ecology with the University of British Columbia, said there's a connection between the increase in calls and the rise in bears being destroyed. Ford explained the lethality of calls to COS has remained fairly steady in the last 10 years: between two and three per cent of them result in a black bear being destroyed.

With that in mind, Ford called it a "huge problem" that data isn't being collected on why calls to COS are increasing.

"We could use some more insights into why people are calling more," he said. "Is someone that saw a bear in 2012 less likely to call the conservation officer service than they are now? I don’t know. That's kind of a social science question. But there are more calls being made. We've got to figure out why."

Attractants key concern

One brown bear that was destroyed by COS last year was nicknamed by the North Shore Black Bear Society "Skinny Brown Bear." The organization said the bear was spotted in the community several times and appeared to be "extremely undernourished." He eventually began sleeping near homes, prompting the organization to call COS for an assessment. Officers determined the most humane course of action was to euthanize the bear.

In a social media post, NSBBS said it believes the bear hadn't fed for weeks due to "a partial blockage in his digestive tract," which is often caused by bears eating garbage. Bears are driven by smell, the organization explained, and may swallow packaging that has food odours on it.

NSBBS says most bears are killed for finding food around homes or for entering a confined space. Reisner said more work needs to be done to reduce attractants and unnatural food sources like garbage, compost, bird feeders and untended fruit trees.

Skinny Brown Bear is seen in this photo shared by North Shore Black Bear Society. (Craig Devisser)

Skinny Brown Bear is seen in this photo shared by North Shore Black Bear Society. (Craig Devisser)

"It's really our responsibility as residents of bear country to really understand how to manage those attractants and what we should be doing to prevent that sort of thing from happening," she said.

"When bears are coming in and accessing those unnatural food sources, sometimes what can happen is that can lead to a report (to COS) and it can lead to enforcement. So I view that as an unnecessary bear death because it's preventable."

Ford agreed the public plays a role in preventing the deaths of bears.

"It's not necessary for people to behave irresponsibly and lead to conflicts with black bears," he said. "It's a question of what are people doing to increase the interactions, certainly the negative interactions, between bears and people. How are they doing with respect to managing attractants and food conditioning or habituating black bears."

Ford said some municipalities are working hard to manage waste and reduce attractants, but just 10 have Bear Smart status within the province. That designation is awarded when a community fulfills a set of criteria including creating a bear-human conflict management plan, implementing ongoing education and developing a bear-proof waste management plan.

Butler explained when an officer is called about a black bear, they first try to assess what is bringing the animal to that area.

"They just don't generally walk around where there's a lot of people so we know there's generally an attractant. Then how are we going to deal with the bear safely? And that's huge," he said, adding that conservation officers' training is "constant" and includes predatory attacks, wildlife health and wildlife conflict.

While conservation officers are certainly concerned about 2023's record-breaking bear deaths, Butler believes not much can shift until attractants are better managed.

"Public safety is our utmost concern and that can't change," he said. "We're realizing until something changes in the public with the communities controlling attractants, we're still going to constantly have these issues. And just to say you can't destroy is not a solution."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

BREAKING Celine Dion performs at the 2024 Paris Olympics

Beloved Canadian icon Celine Dion made her much-anticipated appearance during the closing of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games opening ceremony.

Jasper wildfire: 'Several weeks' before Jasper can return, premier says

Premier Danielle Smith said Friday afternoon in Hinton while weather conditions are cooler, the Jasper fire is still considered out of control and that Jasper residents can expect to be away from their homes "for several weeks."

'He was just gone': Police ramp up search for vulnerable 3-year-old boy in Mississauga, Ont.

Police in Mississauga are conducting a full-scale search of the city’s biggest park for a non-verbal toddler who went missing Thursday evening. Sgt. Jennifer Trimble told reporters Friday morning that there has been no trace of three-year-old Zaid Abdullah since 6:20 p.m., when he was last seen with his parents in Erindale Park, near Dundas Street West and Mississauga Road.

Driver charged after flashing high beams at approaching police

Orillia OPP arrested and charged a driver with impaired driving after flashing their high beams.

Canada's Christine Sinclair: 'We were never shown drone footage'

Canada soccer great Christine Sinclair said on Friday national team players were never shown drone footage during the more than two decades she was on the team, following a spying scandal that cast a shadow over the Canadians at the Paris Games.

Winnipeg senior's account overdrawn $146,000 for water bill

A Winnipeg senior is getting soaked with a six figure water bill.

Irish museum pulls Sinead O'Connor waxwork after just one day due to backlash

An Irish museum will withdraw a waxwork of singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor just one day after installing it, following a backlash from her family and the public, it told CNN in a statement on Friday.

At least 4 buildings burned at Jasper Park Lodge, others damaged: Fairmont memo

The Fairmont Jasper Park Lodge said Thursday afternoon most of its structures are 'standing and intact,' including its iconic main lodge.

She couldn't stop thinking about the guy she met at the Athens Olympics. Then a message from him changed her life

Omaira Gill grew up counting down the days to each Olympic Games. She wasn’t especially sporty, so she ruled out the prospect of competing pretty early on. But she still harboured Olympic dreams – even just spectating would do.