More than five patients a day are left waiting more than 40 minutes for an ambulance in high-priority cases in Metro Vancouver, as the province’s emergency response system scrambles to catch up to increasing demand, according to documents obtained by CTV News.

Last winter, that number rose to almost 11 patients a day for emergency “Code 3” calls that require a lights-and-sirens response, according to individual records of calls provided after a freedom of information request.

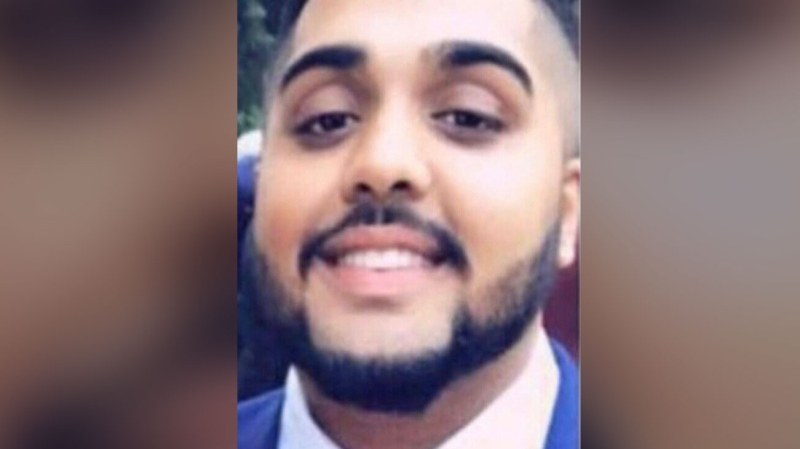

One of those cases was Andrew Cho, who was suddenly paralyzed in his Vancouver apartment in January when a blood vessel burst in his spine.

He fell to the ground, and his iPhone bounced a short distance away.

“My arms and legs weren’t moving,” said Cho. “The only thing I had moving at the time was my neck and chin. So I crawled using my chin. I unlocked the phone with my tongue and used Siri to call 911.”

Firefighters were dispatched ten minutes after the call started as a lower-priority call, and arrived 12 minutes after that to break down Cho’s door and check on him.

They found his case was much more serious and he needed paramedics – but when they called for help, it took the ambulance a further 55 minutes to arrive, even though his apartment is just blocks from St. Paul’s Hospital.

“One ambulance was headed my way, but it was rerouted,” Cho recalled. “It’s a terrifying feeling to be in that position when you need help to be sitting there waiting.”

Cho’s case isn’t the only one – nor was it the only one that night. Records show on January 6, 11 other lights and sirens calls in Metro Vancouver took more than 40 minutes, just higher than the January average.

That was when Metro Vancouver was reeling from snowstorms, seasonal flus, and overdoses in a opioid crisis that is taxing resources of BC Ambulance Service.

In a 12 month period, from October 2016 to October 2017, the documents show 2,056 patients waited more than 40 minutes in Code 3 calls. That is a small fraction of total calls – some 850 a day in the Lower Mainland – but they are coded highest priority, which can include a stroke, cardiac arrest, chest pain, or uncontrollable bleeding.

About two thirds of those calls are like Cho’s: lower-priority calls that are eventually upgraded when dispatchers realize the case is more serious. For example, this can happen when a passerby calls in on a cellphone with limited information, the call is given code 2 priority, but then another 9-1-1 call can upgrade the call.

Each call is handled individually by dispatchers who can dispatch local fire departments to arrive more quickly, and who can prioritize which of the high-priority calls need attention first.

BC Emergency Health Services head of dispatch Neil Lilly says the service has been working on catching up to demand that’s increasing some 6 per cent a year.

He says BCAS did an external review of its service and is now injecting $91 million into the service.

“We had a really bad winter last year with increased snow in the Lower Mainland. We had the opioid crisis. When you put in those added extras into it which have really impacted us, we’ve responded quickly to those difficult situations to add extra resources,” he said.

“You’re going to see steady improvements in our response times for all patients. We’re making sure that we do everything that we can to make sure we reduce those response times,” he said.

Lilly said the service is changing deployment plans, adding paramedics, and putting paramedic specialists into the dispatch centres to keep a watch out for unusual cases like Cho’s. He said dispatchers are also taking some low-priority calls and rerouting them to different services, such as the nurses line.

The union of paramedics, the Ambulance Paramedics of B.C., says the measures are good – but they may not be enough to catch up.

Dave Deines pointed to a 2012 study that said the Lower Mainland still needs 22 more ambulances. “We don’t have 22 yet, that’s for sure,” he said.

“Eventually this is going to cause a serious medical problem,” he said. “Could be life or death.”

When Cho was brought to an emergency room he was in surgery quickly to relieve the pressure on his nerve. He was still paralyzed, but feeling slowly returned to his body, and with extensive physiotherapy at GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre, he learned to walk and then to run.

He completed a half-marathon this summer.

“Obviously I’ve had an incredible outcome,” Cho said. “Honestly it’s upsetting of course because I don’t know if all of those people have had as positive outcomes as I have,” he said.