Vancouver’s police officers spend a mandatory minimum two days a year running training scenarios, and CTV News Vancouver reporter Allison Hurst got a chance to participate.

Here’s her account:

I put on a GoPro with a practice gun weighing heavily in one hand, and pepper spray in the other. Along with a partner we were about to respond to a call for a domestic incident.

"Hi, police," I yell as we enter the dark room. A woman was on a bed with blood on her face, and a man in the corner was holding a crowbar.

"He didn't take his meds," she said as we entered the room.

These training scenarios are called "reality based training" and are designed to prepare officers for a real life call.

"It allows what we call training blueprints to occur," said instructor Clive Milligan, who is also a retired sergeant from the Vancouver Police Department. "Although the environment might be a bit different, the counter attacks will probably be the same."

For me, doing something like this was a first. After learning the man was having a psychotic episode, we managed to talk him into dropping the crowbar and peacefully end the scenario without firing a single shot, much to my relief.

But then we started the second scenario.

I was with my partner sitting in a Starbucks, having coffee. There was a man on the phone who sounded upset, another one who didn't get what he ordered, and a third asking us questions about becoming a police officer.

"I'm going to kill you," a man yells as he enters the "coffee shop."

Shots were fired, and that time I discharged my firearm.

"There's a lot of emotional stress happening," said Milligan with physiological responses to rapidly unfolding encounters.

Milligan told us in the last decade these reality based training exercises are the best way to get officers ready for the field. They use actors instead of members of the police force.

"They're given reality based training equipment that acts and functions like the real pistol. Like the real pepper spray, like the real baton but it's relatively safe," he said.

The guns we were using fire blanks, but sound very real, and the pepper spray is filled with water.

There are times when use of force is necessary, said Mulligan.

They ran us through a scenario on that too, where a woman was refusing to be handcuffed, by lying on her hands. She yelled and screamed "don't touch me" while others pretending to be the public, filmed us on cell phones.

"Some of the techniques we do use are based on principals of human physio kinetics," said Mulligan, explaining how police use pressure points and range of motion to detain suspects.

We were never able to get the woman off the ground and into handcuffs. Instructors showed us how they would do it.

"We want the officers to recognize that you're not probably going to use force but if you have to you need to have that option open to you," said Milligan. But he explained, if an officer does, it has to be done for the right reasons.

"It has to be reasonable, it has to be justified, and it has to be for non-punitive purposes."

Force doesn't make up much of the job: VPD

According to numbers from the Vancouver Police, their officers use force on average 0.05 percent of the time, and respond to 240,000 calls a year.

In 2019 numbers provided to CTV News, Vancouver Police say none of their officers have discharged their hand gun so far, beanbag guns have been fired 18 times, and on 20 occasions, a Taser was deployed.

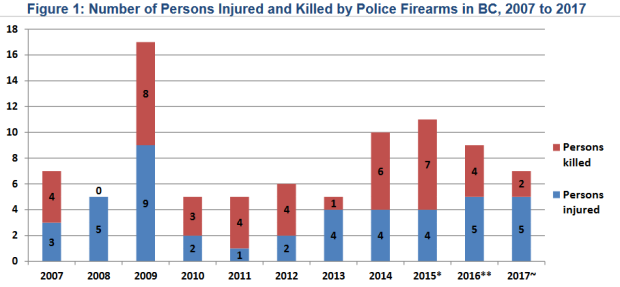

The Policing and Security Branch has data from 2007 to 2017 which breaks down provincial stats. Based on those numbers, on average each year, police discharge their fire arms 13 times. And they've found on average 4 people are killed by police firearms annually.