From kids stealing pads or tampons, to women working 12 hour shifts with no access, and grad students using toilet paper to deal with menstruation, Nikki Hill has heard a lot of examples of women dealing with what’s dubbed "period poverty."

Hill is the volunteer co-chair of the United Way’s campaign called Period Promise which aims to help those who may not be able to afford period products or have access to them when needed. Now, the organization will take $95,000 from the province to research where the need is, and how best to distribute products.

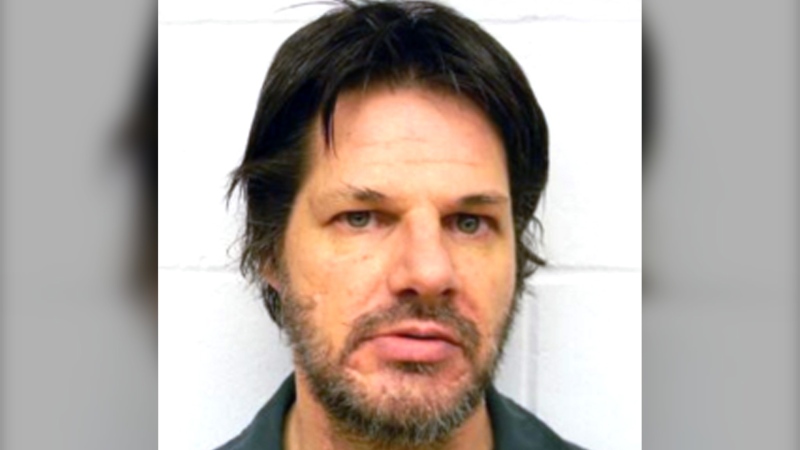

"This is just a basic equity issue for those who menstruate," said Hill at an event at Kiwassa Neighbourhood House to mark the launch of the project. "The work for the Period Promise campaign and this project will only continue to level the playing field."

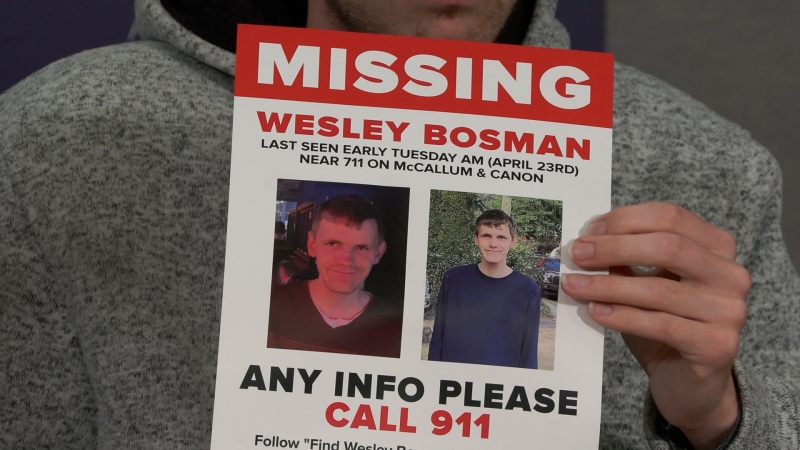

Always and Tampax are providing pads and tampons at a discount for the research project, which allowed the United Way to expand from eight sites to 12. The non-profits are located around the province will distribute the products for free (see table below), and collect data on how best to reach those who need them. The pilot project will run for a year with a final report going to the province in December 2020.

"No one knows really knows how big this is in British Columbia," explained Neil Adolph, who is the project lead for the period promise campaign. "Our central hypothesis is this is a bigger issue than we know, and this is going to be the first opportunity for us to get a sense of what that looks like."

In 2016, the United Way launched "Tampon Tuesday" to collect and distribute period products to those in need. The need was so overwhelming, said Hill, they knew immediately how big an issue it was.

She says they began hearing from agencies about the demand for period products, the same request came from teachers, and staff from social service delivery programs gave examples of having to pick up kids after they were caught stealing products.

"We hear from teachers that they have kids missing school here in B.C.," said Hill. She added addressing that issue alone means not only providing products in school but also in other places around the community.

In the first year, Tampon Tuesday collected about 30,000 products and Hill says they were gone almost immediately. In 2017, 100,000 products were again gone virtually immediately. In 2018, half a million products were collected and distributed. Along the way, organizers realized the need was so great they had to move beyond collection and distribution to advocacy. The United Way decided to pursue the Period Promise model that other countries had implemented. In 2018 the United Way also started working behind the scenes to urge the provincial government to address period poverty as part of its poverty reduction strategy.

In early 2019, the issue was picked up by the New Westminster School District, after hearing Vancouver mom, Selina Tribe talking about the issue of kids not being able to access period products in school washrooms. After the district voted to provide free products, discussions were already underway with the province.

In April the government, announced every school district in B.C. would need to provide period products in school bathrooms, meaning students could avoid making a trip to a school office to ask an adult for them.

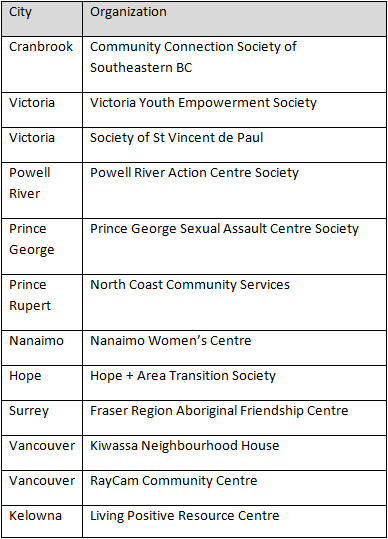

Social Development Minister Shane Simpson, said the insight gathered from the research project will help government come up with long term public policies. Simpson said the work fits in with the aim of reducing poverty in the province.

"Our expectation is that we’re going to learn a lot about what the impacts of period poverty are on inclusion, on creating opportunities for people to make changes in their lives," said Simpson.

Hill says the United Way has also looked at the impact on the Trans community as part of its efforts around inclusivity. She says more and more organizations are signing up as part of the Period Promise campaign to provide free access to products.

The next step she says may be post-secondary institutions.

As for those who suggest this isn’t a good use of taxpayer dollars, Hill said there are still a number of women’s health issues that are misunderstood, but she thinks when people understand the problem, they can see the need for it.

"It’s become a passion project, because it really was a big check on my own privilege to walk through my daily life and not think about just the extent of the project and the more we do, the more we find out," said Hill.