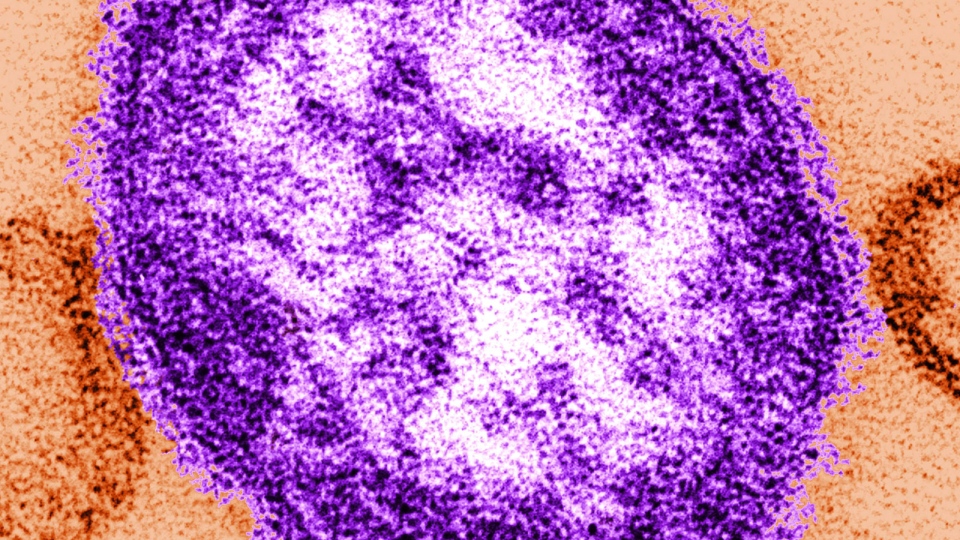

Despite a measles outbreak that infected more than 200 people this month, don’t look to the more religious Fraser Valley to find the lowest vaccination rates in the province.

Instead, in 2012 that dubious distinction belonged to a community known for its health-conscious, natural and organic outlook -- Vancouver’s North Shore.

Just 63.5 per cent of kindergarten-age children in North Vancouver and West Vancouver were vaccinated against diseases including polio, tetanus and whooping cough. That means about one in three children weren’t protected: the lowest rate in the province.

“That’s pretty low. It wasn’t good,” said Dr. Meena Dawar, the public health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health. “We were very concerned about it because it was not good enough.”

And with low vaccination rates, diseases like whooping cough were taking hold, with hundreds of infected people that year, she said. Whooping cough is a highly contagious bacterial disease that results in some six weeks of continued coughing, known for its high-pitched “whoop.”

The disease can be fatal, especially in young children, and hospitals on the North Shore were seeing severe cases.

“As expected the disease rates were highest where the coverage was lowest,” said Dr. Dawar.

There is a small portion of the community, between two and five per cent, who refuse to vaccinate because they object on philosophical grounds, said Nicole Roy, the immunization and communicable disease co-ordinator on the North Shore.

The measles outbreak in Chilliwack started in a community whose pastor has warned against the negative effects of vaccination.

But religious or philosophical objections alone couldn’t explain such low rates on the North Shore. One factor was the impression among the community that vaccines somehow weren’t “natural.”

“Definitely many of our parents are going the natural route and in some circumstances that’s okay. But when it comes to vaccines, there’s not a natural alternative to science,” Roy said.

Frustrating officials are the debunked myths that vaccines somehow cause autism. But those myths were pervasive enough online that some parents were convinced not to take what they saw as a risk.

“As a scientist the amount of disinformation out there is disheartening and as a parent it’s quite upsetting to see that out there,” said Dr. Dawar.

The health authority sprang into action, identifying other problems, including lack of availability of vaccination clinics, and a lack of data on some children who may have gotten vaccinated through a family physician who may not have updated records.

The authority created more accessible clinics, put posters and flyers out to educate the public, and got in direct contact with parents.

“We did a really big push last year. Our nurses called individual families that we knew were not protected, or that we didn’t have records for. The nurses had conversations with these families. That made a huge difference,” Roy said.

This year the vaccination rate for the five-in-one vaccine on the North Shore rose to 73.6 per cent, almost the provincial average. It has a long way to catch up to vaccine-friendly jurisdictions like Vancouver, at 81 per cent, or Richmond, at 93 per cent.

The next lowest area identified in the 2012 report was Kootenay Boundary, at 66.6 per cent vaccinated. The provincial average for the five-in-one vaccine is 75.5 per cent. The provincial average for the measles vaccine is 87.8 per cent.

Roy said the experience has prompted Vancouver Coastal Health to explore new ways to get in touch with families to remind them about their vaccination schedules.

“We’re really behind the times. We need to phone people, but if we could text them to remind them, that would be far more effective. Parents are using their mobile devices for everything. Leaving a message on their land line is a really archaic way to do it,” Roy said.

Public education is a huge component, said Dr. Dawar.

“Parents were getting busy, and the other thing is that we’ve lost our fear of these diseases. We don’t see them as often as we used to. We’ve become complacent. We really need to address that,” she said.