'Outraged and distraught': Reaction to disabled B.C. woman's approval for medically-assisted death

A B.C. woman speaking out about “death care” being easier to access than adequate health care is sending shockwaves throughout the country, with disabled advocates, doctors and observers holding up her experience as a potent example of the slippery slope of expanded dying with dignity legislation.

The topic of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) is in the spotlight and many experts, patients and advocates have testified at a special committee that the elderly, chronically ill and disabled are at risk of feeling pressured or cornered into choosing to die under expanded legislation – which is exactly what “Kat” described.

The woman in her late 30s asked to be referred to with a pseudonym and does not have a terminal diagnosis but is in constant pain and now experiencing organ failure due to complications from Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, so she applied to the Fraser Health Authority for assisted death in the hope it would lead to more medical or social supports.

“If I'm not able to access health care am I then able to access death care?” she said of her thought process. “My suffering was validated to the extent of being approved for MAID, but no additional resource has opened up.”

Disabled Canadians who have been holding marathon roundtable discussions on MAID and the implications for the vulnerable cited her situation the day after Kat spoke up.

“We are raising our voices because Kat and many others like Kat need us in their corner,” said Disability Filibuster participant, Catherine Frazee. “We are still outraged and distraught with every new report that one of our kinfolk have succumbed to a MAID application.”

Others are taking to social media voicing similar concern and dismay at the details.

GROWING NUMBERS TURNING TO MAID

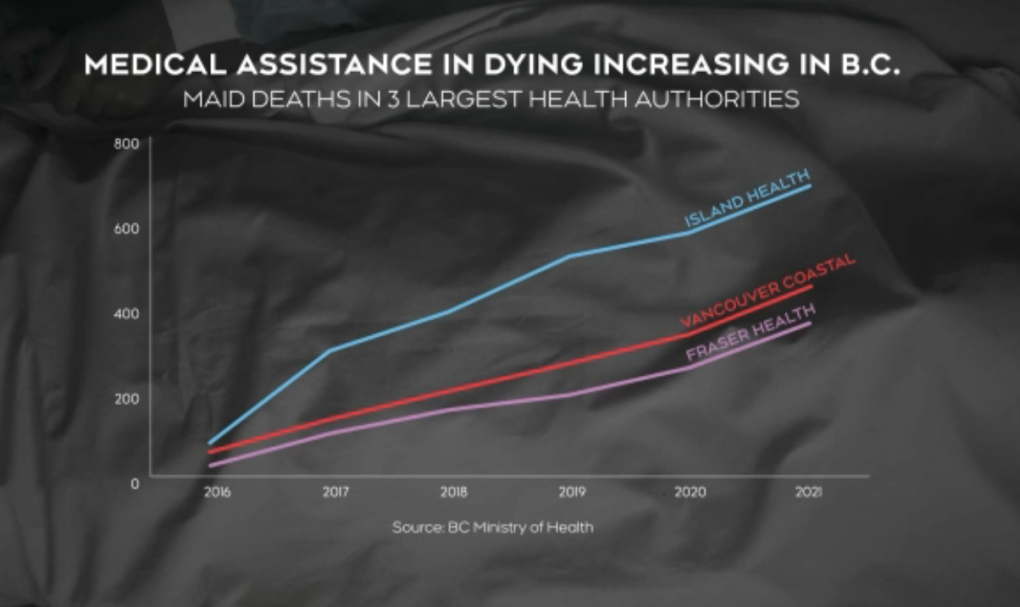

There is no doubt that since the laws changed to allow medical personnel to help suffering people end their lives, there’s been a steady increase in the number of people choosing to do so.

Of the three most populous health authorities, Island Health saw the most deaths per capita and has the highest rate of MAID in the country. The Ministry of Health says in 2016, 80 people had MAID compared to 683 in 2021. In Fraser Health, there were 26 and 361, while Vancouver Coastal Health had 57 and 445 in those years, despite much larger populations in those two regions.

CTV News asked the ministry for the number of applicants for each of those years, but a spokesperson claims they don’t collect that data.

A peer-support network that provides guidance and information to those considering MAID says they’ve seen a tripling of web traffic, engagement and registration since they established their volunteer service when MAID started in 2017.

“Every week we're getting more and more requests where people say 'I just need to talk to someone,'” said Bridge C-14 CEO Lauren Clark, who confirms that some of those people do not want to die but feel they have few other options amid poverty, disability and a lack of access to resources.

“There are individuals who this is their experience,” she said. “They're navigating this all on their own and they are trying to fight a system that hasn't been supportive of them."

WHAT COMES NEXT?

As the special committee of parliamentarians and senators begins writing its draft recommendations to government, observers say it may be public pressure that has the biggest result.

“My sense is that members of the public may not have appreciated how the legislation would impact people with disabilities living in poverty,” said Kerri Joffe, a lawyer with the ARCH Disability Law Centre in Ontario.

She pointed out that the expansion to include people suffering but without a reasonably foreseeable death happened during the pandemic, when COVID-19 was dominating everyone’s lives. Already, United Nations representatives have raised concerns about “ableist assumptions about the inherent 'quality of life' or 'worth' of the life of a person with a disability,” noting disability is not a burden or defect.

“Tragically those warnings have now become reality and that's what I think is really shocking,” said Joffe. “It really should give us all pause (before expanding further).”

For its part, Fraser Health insists it’s doing enough for the people with serious health issues living within its jurisdictional boundaries.

“Our role is to support people in accessing appropriate health resources and services that best meet their care needs,” wrote a spokesperson. “If a person is low-income and is experiencing financial barriers to accessing care, we will support them in understanding how they may access health supports or services not covered under MSP, if funding supports are available.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

BREAKING Police question man with gun, suppressor and fake IDs in Pennsylvania in connection with health care CEO killing, sources say

Police are questioning a man in Altoona, Pennsylvania, in connection with the shooting and killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, two law enforcement officials familiar with the matter tell CNN.

Family spokesman says slain Edmonton security guard had only been working 3 days

A spokesman for the family of a security guard who police say was murdered while patrolling an Edmonton apartment building last week says the man had only been on the job for three days.

Sask. hockey player recovering after near fatal skate accident during game

The Sask East Hockey League (SEHL) has released details of a near fatal accident at one of its games over the weekend – which saw a Churchbridge Imperials player suffer serious injuries after being struck with a skate.

GST break could cost Ottawa $2.7B if provinces don't waive compensation: PBO

The federal government's GST holiday would cost as much as $2.7 billion if provinces with a harmonized sales tax asked for compensation, the parliamentary budget officer said on Monday.

BREAKING Canadian government to table fall economic statement next Monday

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland is set to table the federal government’s fall economic statement next Monday, the government announced today.

Hazardous conditions expected in some parts of Canada with weather warnings in effect

Hazardous conditions are expected in some parts of Canada this week.

Police search for three men who escaped from immigration holding centre in Quebec

Authorities are searching for three Chilean nationals who escaped from the Laval Immigration Holding Centre north of Montreal.

Celebrities spotted at Taylor Swift's final Eras Tour performance in Vancouver

Taylor Swift fans from around the world gathered in Vancouver on Sunday to witness the final performance of her massively popular Eras Tour, including a few celebrities.

The Canada Post strike involving more than 55,000 has hit 25 days

The Canada Post strike involving more than 55,000 workers has hit 25 days.