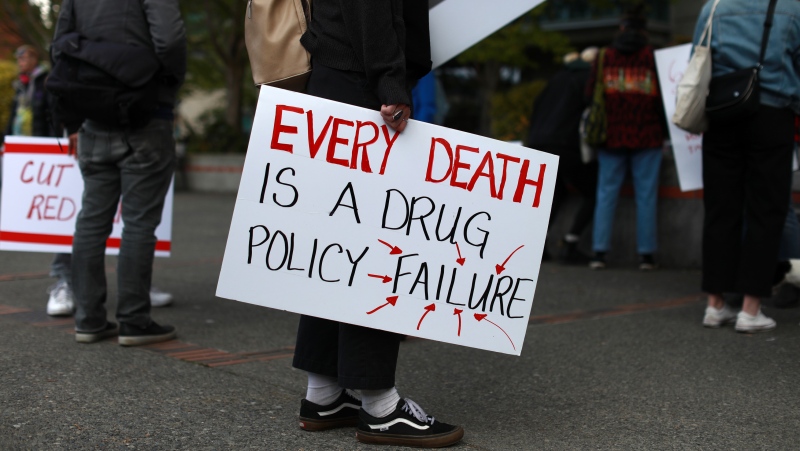

The First United Church in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside says it was forced to turn away dozens of desperate people overnight because the city ordered them not to exceed their occupancy limit for the first time in three years.

The building is allowed to hold 240 people at any given time, including staff and volunteers, but Rev. Ric Matthews says the shelter has frequently surpassed that number because there's nowhere else for clients to go.

At least 27 people were turned away on Wednesday night, he said.

"[They] were met and face-to-face were told that, despite the fact that we know you and care about you and relate to you and understand that you have nowhere else to go, you cannot come into this building," Matthews said.

Jason Watt, who has worked at the shelter for two years, described rejecting regulars who were begging him to come in from the cold as a devastating experience.

"I just tried to keep a straight face until the morning time," Watt said. "It wasn't until 8 a.m. when my shift replacement came that I finally got choked up about it.

"Last night was probably the worst shift I've ever had to work."

Matthews said authorities have been well aware of the shelter exceeding its occupancy, particularly during the Olympics when organizers were urged to keep people off the streets.

The shelter regularly accommodated more than 300 people per night during that time, he claims.

But Mayor Gregor Robertson says that increasing demand for shelter space means it's time for strict enforcement of fire regulations.

"They've worked within a margin of being slightly over, slightly under based on their funding and the needs of the community, What's clear now is we don't have capacity in our shelter system and they're getting more people coming to their door -- way more than can fit in that building," he told reporters.

The city says it can provide buildings that that house 160 beds, but needs provincial funding to run those shelters.

"It's just deplorable that the B.C. government isn't responding more proactively on this, and that we end up in crisis yet again," Robertson said.

For months, the housing minister has said not to expect funding for cold-weather housing, arguing that a blend of permanent and temporary homes is the way to end homelessness.

With a report from CTV British Columbia's Bhinder Sajan