VANCOUVER -- B.C.’s better-than-average performance relative to other provinces during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic is largely tied to its response to hotspots, which other regions addressed with mixed results, according to a Vancouver infectious disease specialist.

Canadian provinces’ pandemic curves vary widely. Second waves tend to be considerably worse than the first ones, and third waves chart even more infections, except in Quebec, which had the worst infections and death tolls at the start of the pandemic, but a significantly lower third wave compared to other areas.

Dr. Brian Conway, president of the Vancouver Infectious Disease Centre, says Quebec used the tools at its disposal the best to counter the unique challenges of the third wave.

“It really is the rise of the variants and the rise of the hotspots,” said Conway. “That's why we're seeing Nova Scotia, Alberta, Manitoba setting records and we're seeing certain parts of British Columbia being severely affected and other parts like Vancouver Island being almost completely spared.”

He identified three key strategies that control viral spread as determining how each province eked its way out of the third wave.

- Public health measures – Restrictions, guidelines and other instructions that limited interpersonal contact. Quebec instituted curfews and restrictions on a regional basis, while B.C. eventually closed indoor dining and limited intraprovincial travel with an ongoing “circuit-breaker.”

- Testing and contact tracing – The more aggressive and thorough, the greater the ability to spot transmission networks and shut them down. B.C. health officials have repeatedly come under fire for low testing rates relative to the rest of the country.

- Strategic vaccinations – Provinces that prioritized some of their vaccine doses in hotspots saw smaller flare-ups because they reduced the number of people the virus could jump to. This is something B.C. has done since supplies first arrived, but Alberta failed to do; that province now has the highest infection rate in North America.

"If you put all of that together and do it exactly right, you put out the hotspots, and if you don't, then spread continues,” said Conway. “So it turns out that Quebec, for a number of reasons, did all of these things right, probably across the entire (country) and it's led to the results we're seeing today."

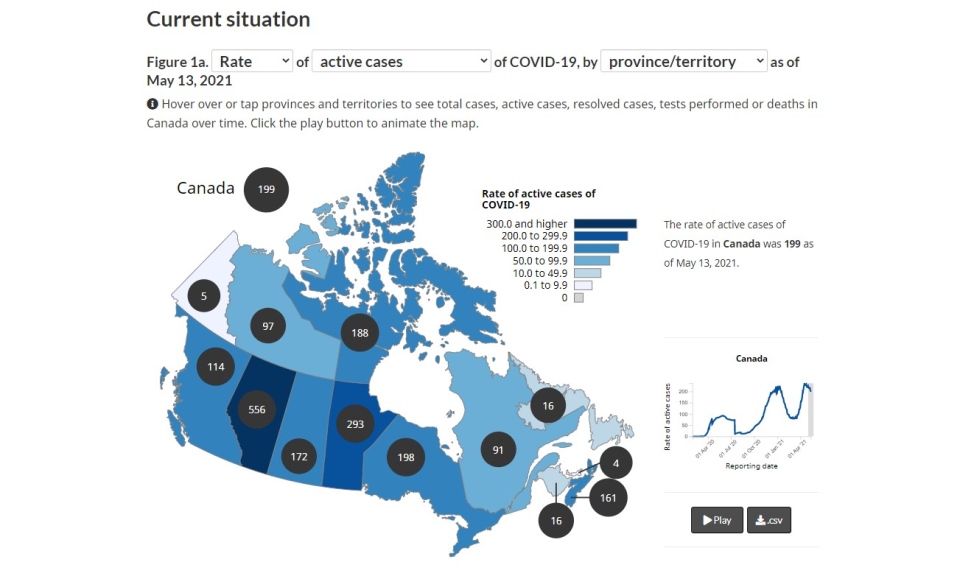

When it comes to active cases as of Friday afternoon, B.C.’s per capita caseload sits at 114 per 100,000 residents, with Ontario at 198 and Alberta at 556. Quebec only has 91, while the national average is 199.

BCCDC warns of Alberta spread

While British Columbia saw reasonable success using the three pillars of viral control, Alberta floundered and for at least two weeks the B.C. Centre for Disease Control has warned public health officials of the potential consequences.

“Alberta’s case rate continues to be the highest of all jurisdictions in Canada and the U.S. (~3.3x the B.C. rate),” reads an internal BCCDC report that was made public in the wake of intense backlash.

“Potential for importation into B.C. is high.”

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said she’s been discussing the issue with Northern Health officials, but it’s not easy to stop interprovincial travel.

“There’s a number of reasons people go back and forth, particularly in the Peace Region, and it is challenging,” said Henry on Thursday. “We know that a lot of it is work travel, so we have done a concerted effort working with some of the industrial camps and mines in those areas to immunize workers, particularly the rotation workers who are coming through.”

Dr. Leyla Asadi, an infectious disease specialist in Edmonton noted that while Alberta’s premier tried to model the “soft hands” approach of B.C. with few restrictions and reluctance to enforce or ticket, the slow response to the rising infections of the second wave made it hard to start bringing infections under control.

“Earlier action allows you to both take more limited action and to see the effects more quickly, and I think that the biggest distinction between British Columbia and Alberta was B.C. acted a few weeks faster, a few weeks earlier and didn't have the same number of cases to climb down from," said Asadi. “We were weeks behind and those weeks matter. The sooner you act, the sooner you can see your places come down. I would say that's the single biggest thing."

Alberta neither shut down workplaces nor targeted hotspots for vaccinations, opting to largely follow an age-based vaccination rollout. B.C. has had several parallel streams, but devoted considerable resources to workplace and community outbreaks and has lowered the age threshold in hotspot neighbourhoods.

Asadi points out that Alberta Premier Jason Kenney also faced a revolt from more than a dozen MLAs who wrote a letter opposing more restrictions in the third wave, and did little top stop the “No More Lockdown Rodeo Ralley” in Bowden as infections sored to 2,433 new cases in a single day.

"I think it's important to not lay the blame on Albertans,” said Asadi. “This is a leadership issue and that means it's an issue we can solve."

Surrey a bellwether for reopening

With hotspots driving the third wave, Conway says Surrey will be the key to determining when and how B.C. will end its current restrictions.

"In British Columbia, we've made a decision that we're not going to have an regional public health measures, so we're either opening things across the entire province, or not,” he said. ”We need to help the people that are living in Surrey. We need to be a whole, all-of-province team and try and figure out together how we're going to get Surrey to not be a hotspot so we can all reopen."