VANCOUVER -- A leaked presentation from the province’s biggest health authority contains details that have the BC Teachers' Federation calling for a switch to hybrid learning in COVID-19 hot spots, while an infectious disease expert says the province is trying to demonstrate schools are safe rather than asking if they actually are.

A 37-page presentation titled “COVID-19 school cluster and transmission analysis” dated May 7, was conducted by a team of medical health officers and epidemiologists in Fraser Health from Jan. 1 to March 7, and includes public and private schools.

It’s a more detailed description of the high-level information Dr. Bonnie Henry presented during her monthly modelling presentation in mid-April and includes critical new information: not only were 52.5 per cent of transmissions between students (9.7 per cent were staff-to-staff, 21.4 per cent staff to student), but a map outlines the fact 35 per cent of Surrey schools had confirmed clusters or outbreaks during the nine-week period.

“It’s the opposite of what we were told earlier on and it really does spell out the need for physical distance and mask wearing — for a long time it was only the adults in the building wearing masks and we really had to fight for that policy,” said BC Teachers Federation president, Teri Mooring.

She also pointed out the study was done at a time variants accounted for a small number of cases and were not yet the majority as they are now. She's is calling for a change in the learning plan for hot spots through the end of the school year.

“We would like to see in those hard-hit regions, especially Surrey and the Peace River Region, where there could be a hybrid model put in place for a few weeks even,” she said. “It would not be difficult, it would mean that students would still go to school every day, just not all day and they would be in smaller classes so they could physically distance.”

But the public health officer who oversees schools in Surrey and the Fraser Valley insisted the study shows schools are safe.

“There are 315,000 staff and K-through-12 students and of them only a fraction, less than one per cent during our study period, actually developed COVID and the majority came from outside the school, so it was from the community,” said Fraser Health’s Dr. Ariella Zbar, who insisted the contact tracing and testing system can determine whether students brought COVID-19 to school or the other way around. “We found that about a third transmitted it onwards outside of the school and it was mostly within the household setting.”

Zbar pointed out there are considerably more students in schools than staff, so she would expect the highest transmission rates would be between them. She is also opposed to closing schools or moving to a hybrid model as the BCTF urges.

“There are schools in hot-spot areas that aren’t affected at all, and it’s not just the education that’s impacted when schools are closed — it can be a child’s place to get a meal, a safe place for them a place of interaction, so there are tremendous impacts,” she said.

Zbar also insisted the report was always intended to be released to “school partners” and the public, but the report was leaked to reporters late Monday afternoon and Fraser Health didn’t have it on its website until late Tuesday morning; Henry had presented the broad strokes from the report four weeks earlier.

Scant information from Fraser Health, Vancouver Coastal

The study only looked at specific criteria. A single case of an infected staff member or student prompts an exposure notice to the school community, but a cluster isn’t declared until there’s one more case that can be definitively linked to the first one.

An outbreak is only declared when there’s more widespread transmission and isolating the cases isn’t sufficient; that determination is made at the medical health officer’s discretion. Hundreds of cases were excluded because they were “not included in confirmed clusters as additional analysis is warranted to determine if linked or not to in-school acquisition”

CTV News asked Vancouver Coastal Health for a report it conducted with similar findings from September to December, which was also cited in Henry’s April presentation, but the health authority would not provide it. Instead, they pointed us to an old summary of the information and one newly updated chart showing emphasizing community infections outstripping school infections by a wide margin.

B.C. barely looking at school transmission: expert

Experts have long-since argued B.C. doesn’t do enough testing, particularly in schools, and that the long-delayed requirement for masks for Grades 4 to 12 meant the province could’ve done a lot more to curb infections in school settings.

The April 15 modelling presentation came under heavy criticism by teachers and parents, who alleged the information was selected to put the best face forward on school transmissions.

“It seems that B.C. has been on a mission to demonstrate that schools are safe — that’s very different than asking the question ‘Are schools safe?’” said University of Toronto Institute of Health Policy assistant professor of public health, Colin Furness.

The infection control epidemiologist pointed out that Fraser Health’s document doesn’t make it clear whether transmission in a school bus, for example, is considered a school or community setting. He described that as problematic because the enclosed spaces have students at close quarters and at high risk of transmission.

“The elephant in the room here is neither of these studies have considered asymptomatic transmission among kids and yet there is a whole tonne of evidence from a lot of different places that maybe half of all child cases are asymptomatic — and so if you’re missing half the iceberg I think it’s difficult to say you understand the iceberg,” said Furness.

His comments come as the province makes a paradoxical claim: that they don’t have detailed information around schools, but are making decisions based on data.

“I've said many times, we don't have the type of information that I think everybody would like to have which is exactly who transmitted to who and every school and every day care,” said Henry on Monday. “We do have some higher level information and we've had some deep dives that have been done in both Vancouver Coastal and Fraser Health in particular that we've presented to people.”

But Furness points out it may be more accurate for health officials to say they’re not looking for the information, rather than insisting they simply don’t have it or that it’s unavailable when other provinces are doing much more to track and document infections and COVID-19 behaviour in schools.

“If you’re not going and prospectively looking for cases in schools, if you’re not going and doing systematic sampling — and there’s a number of different ways to do that — but if you’re not doing that, you cannot make claims you understand transmission in schools,” he said. “British Columbia cannot make valid claims that it understands transmission in schools based on the measurement that it’s done.”

Zbar said that there are some take-home tests to collect mouth-rinse or gargle samples being distributed in the Surrey School District for families that may have trouble accessing testing, and points out anyone ordered to isolate gets a handout instructing them to go for testing seven days after the possible school exposure, whether they have symptoms or not.

What comes next?

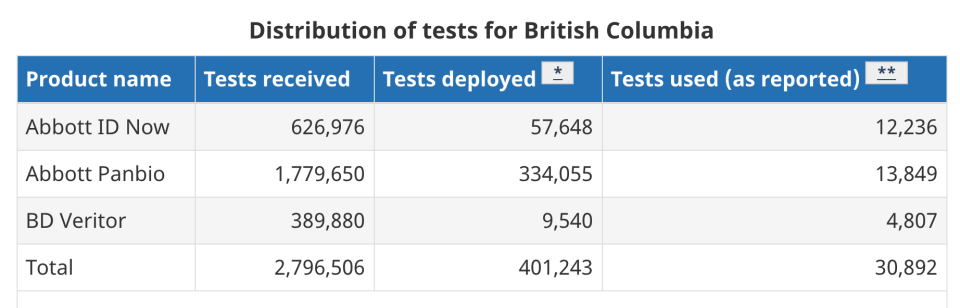

Furness is urging the province to deploy its massive stockpile of unused rapid tests to schools. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, the federal government has sent 2,796,506 rapid tests to British Columbia, which has only distributed 401,243 from provincial warehouses; only 30,892 are reported used.

At the same time, Mooring is pushing for the latest analysis and information about who’s transmitting COVID-19 and in which schools so families, schools and administrators can respond accordingly.

“It feels like information gets hidden when it’s leaked to reporters and that does not instil confidence — especially when this is information we’ve been asking for all along,” she said. “We have an informed public and so this nonsense around presenting data the public doesn’t understand is just insulting and it’s a paternalistic approach that is very frustrating.”

Zbar said Fraser Health intends to look at how both variants and staff vaccinations have affected the situation in schools, but gave the impression it was unlikely that information would be available before the end of the school year.

Henry has often raised legal and privacy issues around her resistance to release more information, citing concerns about stigma. But BIPOC doctors and community advocates have joined academics and other community leaders urging more detailed information.

The high-level, province-wide or regional information provided by health officials undoubtedly has value and is important, but it also overlooks the impression that students in the same city are facing the same risk of exposure.

When CTV News asked Furness whether socioeconomic factors contributing to risk of exposure to COVID and getting sick he agreed, and said that was a key consideration. For example, a student living in a neighbourhood with low transmission rates and parents working from home in a spacious house is at considerably different risk than a student whose parents are both essential workers and living in a multi-generational household in a COVID hotspot.

“We’ve got to understand that asymptomatic transmission in kids is real,” said Furness, highlighting a much-discussed weakness in B.C.’s testing approach. “It happens a lot and kids may not get very sick and that’s a blessing — but that doesn’t mean they’re not getting their grandparents sick and that’s a very different story.”