A new concussion-fighting cap developed by B.C. researchers may help prevent head injury in sport by reducing sharp twisting of the brain during impact.

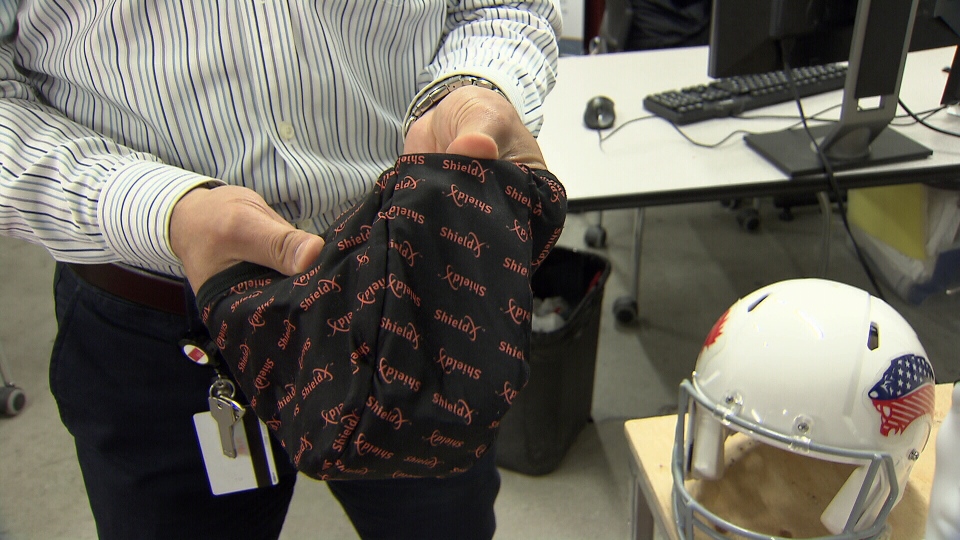

The cap is worn under the helmet and is made of a micro-engineered fibre that can slide on itself, meaning that when a helmet twists upon impact that force won’t be transferred to a wearer’s brain. It allows the head to stay more still and avoid being dragged along with the rotating helmet.

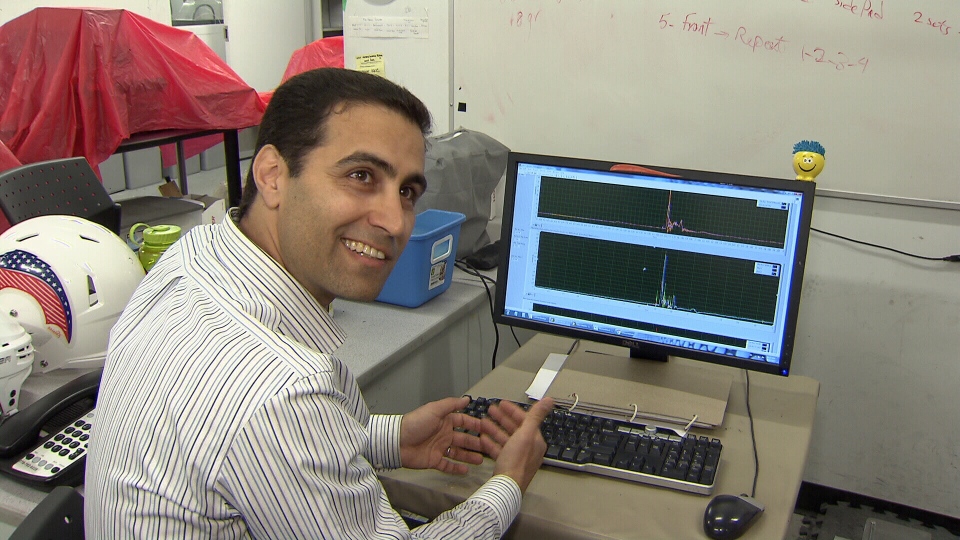

Daniel Abram, a post-doctoral fellow at Simon Fraser University who helped develop the cap for Shield-X Technologies, says the new cap addresses what has been a blind spot for helmets.

“Helmets are designed and certified for compression force only,” he told CTV News. “That’s just one part of the equation. The other part, which is increasingly more important, is called rotational acceleration or sharp twisting of the brain.”

Abram explained that rotation doesn’t have to be big to cause damage—the acceleration during contact is so high that a tiny movement could cause diffuse axonal injury or subdural hematoma. That’s because the brain is floating in the skull, and when the skull rotates the brain will often lag behind—stretching its anchoring axons or even causing it to hit the skull.

Abram and his team have been testing their technology using dummy heads in their SFU lab. He said he’s seen up to 45 per cent reduction in sharp twisting by using the membranous cap.

He says he hopes to eventually work with helmet manufactures to have a membrane like this incorporated into helmet design. He says it could help all kinds of athletes, including cyclists, hockey players, skiers and football players.

Cheryl Wellington, an expert on neurodegenerative disorders and brain injuries at the University of British Columbia, says she likes that Abram is looking at technologies that handle angular acceleration—an area where she sees a gap in research. But evaluating whether a technology is effective at preventing concussions is tough, she says, because so many of the tests rely on kids reporting their symptoms.

“There’s a big difference between clinical and physiological recovery,” she said. “We know… that the brain can still be showing detrimental changes even though the kid is saying they’re just great."

She added that awareness of concussions in sport and how long kids need to recover from them is something people are just beginning to appreciate.

Meanwhile, a Vancouver football coach says he’s seen that awareness improve by leaps and bounds since he was playing football as a kid.

“Back in the day, it was like if I had a headache I’ll go use smelling salts,” Clint Uttley, defensive coordinator for the New Westminster Hyacks, told CTV News.

Now, kids he coaches have to go through graduated steps before playing again after a head injury. They also use protective padded shells on top of their helmets.

“It allows contact to ricochet a bit more and it pads it, so there’s no more direct contact,” Uttley said. “It allows the padded part of the helmet to absorb the blow a bit.”

But technology isn’t the whole story—Uttley’s football team is also changing the style in which they play. He says they’ve switched to a rugby tackling style that protects the head more. They’ve also cut their contact practice days in half.

With a report from CTV Vancouver’s Shannon Paterson.