CTV News Reality Check: BC NDP fumbles ER closures, which will continue

A Vancouver-area emergency department has now turned away patients for a fifth time, showing how the New Democrats' fumbling of doctor shortages is impacting urban and rural British Columbia alike.

While the health minister is keen to recite statistics about net gains in recruitment of physicians and nurses, those gains are not keeping up with a booming population as emergency department closures become more common.

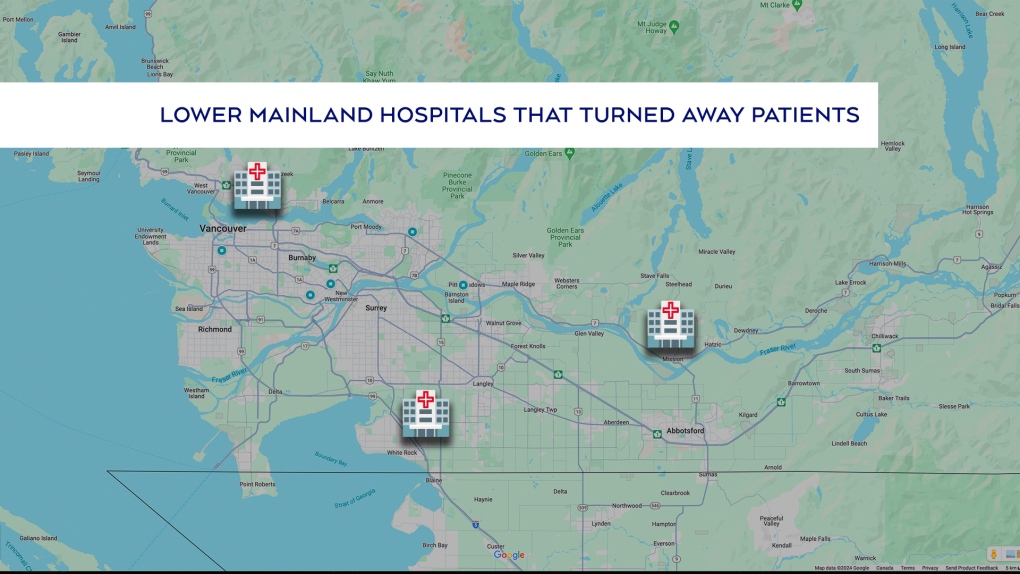

CTV News was first to report that emergency departments at three hospitals have quietly rejected patients at the doors, as the health authorities and provincial officials seek to minimize the “bad optics” of urban service failures.

“The problem will not go away after Labour Day; it won't go away in the fall,” acknowledged Fraser Health vice-president of medicine Dr. Ralph Belle. “I suspect this will be a little bit of a long-term problem.”

He emphasized that every health authority is dealing with a shortage of qualified emergency staff. On Tuesday, he said, officials were scrambling to find last-minute coverage for the emergency department at Mission Memorial Hospital and couldn’t. Fraser Health sent a notification of the overnight closure after the hospital had already stopped accepting patients.

On Wednesday, South Okanagan General Hospital in Oliver was closed midday; some rural and remote diversions last for hours, other communities see multiple overnight outages per week, while some have seen weekend-long closures.

Three hospitals in the Lower Mainland have turned away patients due to lack of staff this summer: Mission Memorial Hospital in Mission, Peace Arch Hospital in White Rock and Lions Gate Hospital in North Vancouver.

Three hospitals in the Lower Mainland have turned away patients due to lack of staff this summer: Mission Memorial Hospital in Mission, Peace Arch Hospital in White Rock and Lions Gate Hospital in North Vancouver.

No new strategies from health authorities or province

Health care may prove to be the Achilles heel for the New Democrats ahead of October’s provincial election.

Health Minister Adrian Dix has repeatedly insisted that they have a plan to recruit and retain doctors and nurses to meet demand, while downplaying staffing as being “a challenge every summer,” but British Columbia never saw patients diverted from emergency departments in pre-pandemic times.

The ministry has pointed out that twice as many health-care workers are calling sick now compared to 2019, and there’s a worldwide shortage of health-care workers as many walk away from the profession due to burnout.

But it’s also true that when John Horgan was leader of the NDP and running for re-election in 2020, he promised a new medical school that he said would accept its first students last fall. The three-year timeline was wildly unrealistic and the school at SFU's Surrey campus is now on track for a 2026 launch, exclusively training family doctors.

In the meantime, sources tell CTV News that doctors’ groups at various hospitals have proposed solutions and new strategies to stabilize the workforce, but that Fraser Health has only paid lip-service to those proposals, at best.

How does B.C. compare to other provinces?

On Wednesday, another email went out to doctors titled “URGENT – Please review.” It offered up to $4,125 to cover “critical to fill shifts” at Peace Arch, Delta, and Mission Memorial hospitals in the coming days.

“Emails go out on a regular basis across the province for help and I understand that other health authorities are struggling as well,” said Belle, who is hopeful an exodus of hospitalist doctors back in to family practice will see long-term reductions in emergency department visits as patients receive more longitudinal, preventative health care.

In the last several years, the NDP government has been at the helm as a Northern Health hospital planned to keep its ER open without a doctor at all, instructing nurses to call 911 in an emergency, while patients at Nanaimo Regional General Hospital received unsanctioned notices that they were being admitted without a doctor to oversee their care.

“These are challenges that are not unique to B.C.,” said Dr. Kathleen Ross, president of the Canadian Medical Association and a family physician in Coquitlam.

Her organization continues to advocate for more training positions, team-based care, and public pressure on policymakers, because “we're in a crisis, no one jurisdiction has this right and we should be looking at national solutions,” she said.

While every province is struggling to provide emergency health care to its residents, British Columbians are unlikely to find comfort in those statistics when they’ve been told by their government that it's working on the issue and has the right plan to keep hospitals open.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Mark Carney reaches out to dozens of Liberal MPs ahead of potential leadership campaign

Mark Carney, the former Bank of Canada and Bank of England governor, is actively considering running in a potential Liberal party leadership race should Justin Trudeau resign, sources tell CTV News.

'I gave them a call, they didn't pick up': Canadian furniture store appears to have gone out of business

Canadian furniture company Wazo Furniture, which has locations in Toronto and Montreal, appears to have gone out of business. CTV News Toronto has been hearing from customers who were shocked to find out after paying in advance for orders over the past few months.

WATCH Woman critically injured in explosive Ottawa crash caught on camera

Dashcam footage sent to CTV News shows a vehicle travelling at a high rate of speed in the wrong direction before striking and damaging a hydro pole.

A year after his son overdosed, a Montreal father feels more prevention work is needed

New data shows opioid-related deaths and hospitalizations are down in Canada, but provincial data paints a different picture. In Quebec, drug related deaths jumped 30 per cent in the first half of 2024, according to the public health institute (INSPQ).

Rideau Canal Skateway opening 'looking very positive'

As the first cold snap of 2025 settles in across Ottawa, there is optimism that the Rideau Canal Skateway will be able to open soon.

Much of Canada is under a weather alert this weekend: here's what to know

From snow, to high winds, to extreme cold, much of Canada is under a severe weather alert this weekend. Here's what to expect in your region.

Jimmy Carter's funeral begins by tracing 100 years from rural Georgia to the world stage

Jimmy Carter 's extended public farewell began Saturday in Georgia, with the 39th U.S. president’s flag-draped casket tracing his long arc from the Depression-era South and family farming business to the pinnacle of American political power and decades as a global humanitarian.

'A really powerful day': Commemorating National Ribbon Skirt Day in Winnipeg

Dozens donned colourful fabrics and patterns Saturday in honour of the third-annual National Ribbon Skirt Day celebrated across the country.

Jeff Baena, writer, director and husband of Aubrey Plaza, dead at 47

Jeff Baena, a writer and director whose credits include 'Life After Beth' and 'The Little Hours,' has died, according to the Los Angeles County Medical Examiner.