Doctors speak up: What's behind waits and closures at B.C. emergency departments

Across the province, B.C.'s health authorities are pleading with doctors and offering hefty incentives to get them to pick up extra shifts, but emergency departments are facing increasing risk of closures, CTV News has learned.

It’s become common in rural and remote communities, but now even Lower Mainland hospitals could see “diversions” – with hospitals closing emergency departments and sending patients to other acute care facilities – in the next few weeks.

CTV News has obtained multiple memos from administrators containing dire language, and reviewed charts detailing unfilled shifts in emergency departments in multiple areas of the province.

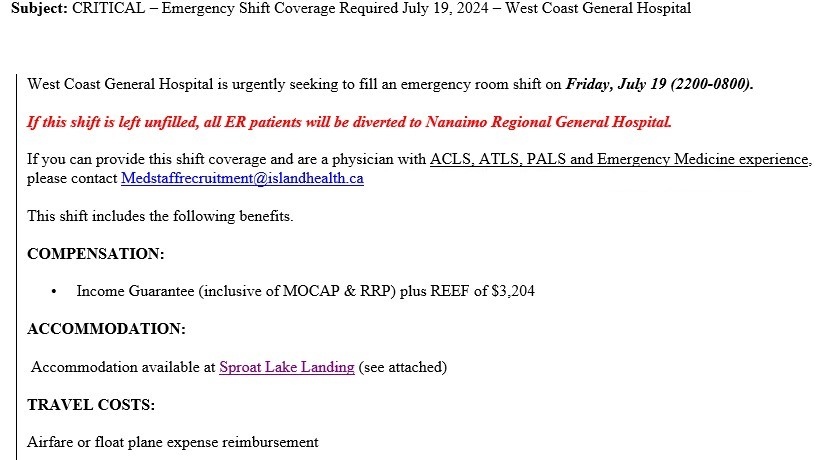

On Wednesday afternoon, Island Health sent an email titled “critical” and pleaded with physicians to work at West Coast General Hospital in Port Alberni overnight on Friday, writing, “If this shift is left unfilled, all ER patients will be diverted to Nanaimo Regional General Hospital.”

It has since been filled, with the health authority offering a guaranteed payment of $3,200 for the 10-hour shift, plus a room at the Sproat Lake Landing Resort and Lodge, meal allowances, and hundreds more dollars for the doctor's travel time and reimbursement of costs.

A memo offering compensation for doctors picking up shifts at West Coast General Hospital in Port Alberni was shared with CTV News.

A memo offering compensation for doctors picking up shifts at West Coast General Hospital in Port Alberni was shared with CTV News.

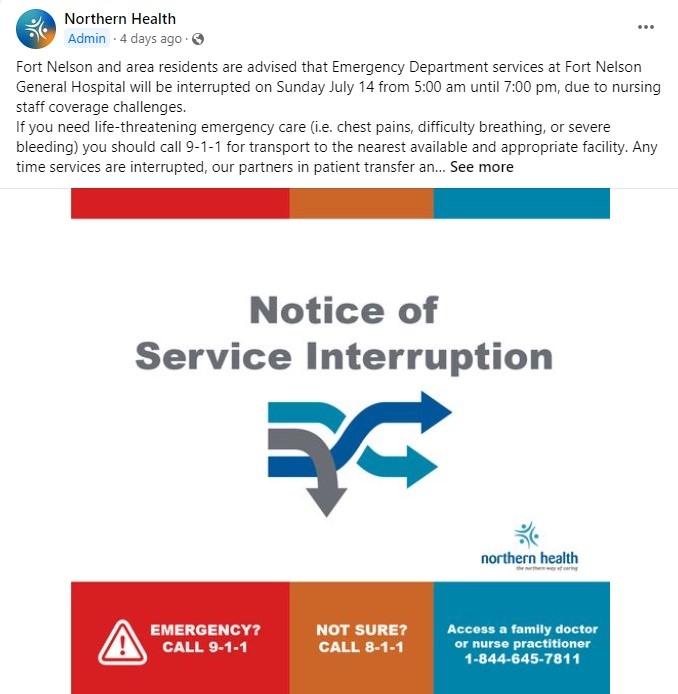

Northern Health is already seeing service disruptions, with multiple emergency department closures in the past two weeks due to doctor shortages, which the health authority has often posted to Facebook shortly before the doors are shut for the day.

Northern Health often posts about emergency department closures on its Facebook page shortly before they take effect.

Northern Health often posts about emergency department closures on its Facebook page shortly before they take effect.

Several front-line sources have expressed frustration that the provincial “Emergency Department Wait Times” website is outrageously out of sync with reality, with actual waits routinely double or triple what’s publicly posted.

Looming issues in Fraser Health

Fraser Health, the largest health authority in the province, serving at least 1.8 million residents, has challenges of its own, even though it’s home to many physicians, nurses, and other health-care professionals. Memos obtained by CTV News paint a dire picture of gaps in the schedule, which employees describe as stressful and demoralizing.

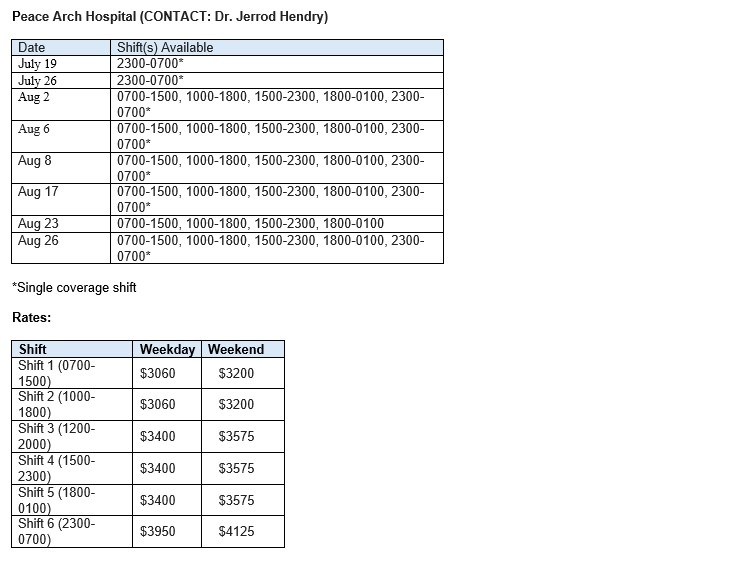

The hardest-hit hospital is Peace Arch in White Rock, where staff have warned administrators they are too short-handed to safely handle patient volume on several nights in July, and six full days in August do not have enough physicians to run the emergency department. Fraser Health is offering between $3,060 and $4,125 for an eight-hour shift, plus travel and accommodation reimbursement for “all critical to fill shifts.”

A table shared with CTV News shows available shifts at Peace Arch Hospital and the compensation being offered for physicians willing to fill them.

A table shared with CTV News shows available shifts at Peace Arch Hospital and the compensation being offered for physicians willing to fill them.

Langley Memorial Hospital is struggling to keep its emergency department open overnight in the first week of August, while Mission Memorial Hospital is critically short-staffed during the days and evenings for the entire month of August; both are officering the same incentives as Peace Arch.

Mission Memorial could see overnight closures as soon as Sunday.

In an email statement, Minister of Health Adrian Dix doubled down on the province's recruitment and incentive strategy as a way to avoid as many service disruptions as possible.

“(Emergency departments) are only ever put on diversion as a very last resort once all other options have been exhausted,” he wrote. “We are not alone in this challenge as Canada and countries around the world are also experiencing a shortage of health-care professionals.”

Doctors speak up

For months, front-line workers have expressed concerns about summer staffing levels on condition of anonymity, for fear there could be professional repercussions if health authorities identify them. Many said there have been repeated warnings not to speak to journalists, even about the impacts on patient safety and availability of medical care.

The president of the Doctors of BC’s Section of Emergency Medicine explained that the reasons for the shortages are complex, but boil down to several factors: lack of government planning and government downplaying of warnings that training space is insufficient; a new contract for family doctors that lured physicians away from hospitals and back into primary care; and a culture shift where doctors are backing away from gruelling 60-to-80-hour workweeks for better work-life balance.

“Now we're in this hole where we're trying to patch it and move forward,” said Dr. Gord McInnes. “It's led us to a point where it's really hard to provide the service we usually provide and it's inefficient and hence the waits increase, the frustration level increases.”

He pointed out that emergency medicine is among the lowest-paid physician specialties, and while more money can address some of the issues, working conditions and the team working around doctors have a major impact.

“Our number one concern is how can we make things better for patients that are sitting in our emergency departments,” said McInnes. “A lot of that comes down to making things better for the people that are showing up to work.”

What other health authorities are offering

An earlier Island Health memo for “Urgent Critical Emergency Department Shifts” at Port McNeill and Lady Minto hospitals warned, “These sites are at risk of closure and disruption if shifts are not filled,” with offers of up to $4,350 for weekend shifts, and indications that “additional incentives may be available.”

Depending on the hospital and the shift, doctors are expected to work anywhere from six hours to 24 hours, which is the requirement for the Merritt and Grand Forks hospitals. A month ago, Interior Health told locums summertime “means we have a higher number of vacancies we need help with filling,” and that, “Any help you are able to provide is helpful!!”

Vancouver Coastal Health appears to be fully staffed in all its acute-care facilities, which several sources describe as better-managed than the other health authorities, with enough support staff and resources to make the work more sustainable.

“It’s not worth it,” said several physicians when asked about the incentives at smaller hospitals, saying they don’t need to put up with the stress and anxiety of working in challenging conditions when larger, well-resourced facilities are also looking for staff.

“We all are overworked,” said McInnes. “But we're trying to do our best that we can and try to maintain the standards that we have for B.C. patients.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trudeau promoting backbenchers in sizable cabinet shuffle coming Friday: sources

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is planning a sizable cabinet shuffle on Friday, and it's shaping up to see several Liberal backbenchers promoted to ministerial posts, sources confirm to CTV News.

Prime minister's team blindsided by Freeland's resignation: source

The first time anyone in the senior ranks of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's office got any indication Chrystia Freeland was about to resign from cabinet was just two hours before she made the announcement on social media, a senior government source tells CTV News.

'Tragic and sudden loss': Toronto police ID officer who died after suspected medical episode while on duty

A police officer who died after having a suspected medical episode on duty was executing a search warrant in connection with an ongoing robbery investigation in North York, Toronto police confirmed Thursday.

Ontario town seeks judicial review after being fined $15K for refusing to observe Pride Month

An Ontario community fined $15,000 for not celebrating Pride Month is asking a judge to review the decision.

The Royal Family unveils new Christmas cards with heartwarming family photos

The Royal Family is spreading holiday cheer with newly released Christmas cards.

EXCLUSIVE Canada's immigration laws 'too lax,' Trump's border czar says

Amid a potential tariff threat that is one month away, U.S. president-elect Donald Trump's border czar Tom Homan is calling talks with Canada over border security 'positive' but says he is still waiting to hear details.

Who received the longest jail terms in the Gisele Pelicot rape trial?

A French court found all 51 defendants guilty on Thursday in a mass rape case including Dominique Pelicot, who repeatedly drugged his then wife, Gisele, and allowed dozens of strangers into the family home to rape her.

Crowd crush kills 35 children at funfair in Nigeria, police say

At least 35 children were killed and six others critically injured in a crowd crush at a funfair in southwest Nigeria on Wednesday, police said.

Scientists think they know why Stonehenge was rebuilt thousands of years ago

Scientists made a major discovery this year linked to Stonehenge — one of humanity’s biggest mysteries — and the revelations keep coming.