VANCOUVER -- Imagine one day going to the drugstore and picking up a rapid test for COVID-19 to use at home, or getting tested before attending a concert, hockey game, or other event, with results in 15 minutes.

A clinical trial now underway at UBC aims to determine whether it’s feasible for people to self-administer a rapid test for the virus.

UBC School of Nursing professor and lead researcher Sabrina Wong said depending on their findings, the test could go forward to seek approval to potentially allow use by the general public.

“We hope to get a total of about 550 volunteers for the clinical trial,” she said. “Some of them are going to do the self-administration of the test, and we’re going to test that against health care professional administered (tests).”

Wong said they’ll also be looking at the sensitivity of the testing compared to the “gold-standard” diagnostic PCR test.

People living and working ar UBC will be eligible to take part, and must not be experiencing any symptoms.

“PCR can catch an infection when it’s beginning, but also when it’s really old, and a person isn’t infectious,” she said. “The rapid test on the other hand, can really detect people who are in that infectious stage, so right at the very early beginning, so it can really break chains of transmission and particularly amongst people who are not attributing any of their symptoms to having COVID.”

A pilot project using rapid testing administered by health professionals that ran on campus from Feb. 9 to April 23 ended up identifying positive cases in 25 asymptomatic students, out of just over 1,000 people tested.

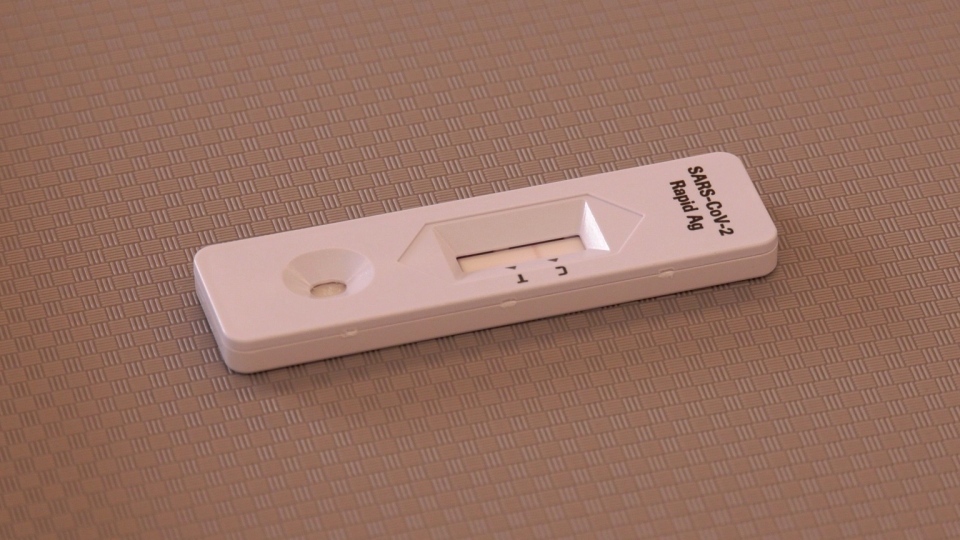

The rapid test which is being used in the clinical trial involves a swab inside each nostril, which doesn’t go as deep as the nasalpharyngeal swab used in the standard diagnostic test. The sample is then added to a liquid solution, which is dropped onto the test device. A line will appear in a window on the device to show the test is working. A second line will appear if COVID-19 is detected.

Wong said the price point for the test is about $5 to $10, compared to the PCR test’s cost of over $100.

“So it’s a lot cheaper, and it becomes more accessible for people to purchase it themselves,” she said.

While B.C.’s restart plan predicts by the fall we could see a return to normal social contact, large gatherings such as concerts and masking only as a personal choice, Wong said rapid testing could still play a role even as vaccination rates climb.

“Vaccination won’t be available for people under 12. So rapid testing could be useful in that population,” she said. “I think that also, as a parent, people would be interested in wanting to ensure when their kid go back to school, their kids can stay in school and they don’t get sent home because it possibly could be COVID.”

Wong added while vaccination will help prevent deaths and hospitalizations, there’s still a lot that’s unknown about the long-term effects of a covid infection, even if it’s a mild case.

“Some of the symptoms that people are experiencing right now with long-haul covid are much like a chronic disease,” she said. “We expect that COVID-19 will end up being like the flu season, or the cold season.”

She said rapid testing could also be useful when people start to take trips internationally again, and can also help with people who are looking for reassurance as health restrictions begin to loosen over time.

“They’re wanting to protect themselves, but also to protect others,” she said. “So it’s really the idea that they themselves may feel anxious about going into different situations that we haven’t been in in the past year. So large events, movies, sporting events, weddings...to help us get back to feeling like, ok, this is going to be OK.”

According to Health Canada, as of May 20 B.C. has received more than 2.7 million rapid tests. Just over 38,500 have been used in the province, with more than 411,000 deployed as of May 18.

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry said B.C. will continue to increase the use of rapid testing when it comes to getting people back to workplaces and communal living settings.

“We’ve been using them...very effectively in places like our correctional facilities,” she said. “The (B.C. Centre for Disease Control) is leading a group that’s been working with businesses as well, to see where these might be useful in businesses as they reopen in the coming weeks as well. So there’s many different settings where I can see them being of value.”

Henry added they’ve also been watching the use of self-testing in the United Kingdom.

“What we hear from our colleagues is that little limited usefulness, in certain situations,” she said.

In an email to CTV News, the Ministry of Health said the province is "using rapid tests more in British Columbia, and we will do more in the future to support our PCR testing program."

“B.C.’s Rapid Point-of-Care Testing Strategy released in March permits wider use in workplaces and settings where there is a higher risk of outbreak and/or transmission including, but not limited to, industrial camps, food processing plants and post-secondary residences,” the ministry said. “This program will continue to be guided by where there is interest and where public health experts deem the tests are most useful to complement PCR testing.”

The clinical trial at UBC is running until Aug. 20.