Exercise decreases risk

Researchers say young girls can help protect themselves from breast cancer later in life simply by exercising.

A recent study tracked 65,000 nurses and found those who began exercising when they were as young as 12 were more than 20 per cent less likely to develop pre-menopausal breast cancer than women who grew up not being active.

Women who ran three hours a week -- or walked 13 hours a week -- had the lowest risk. The study found the biggest impact was regular exercise between the ages of 12 to 22.

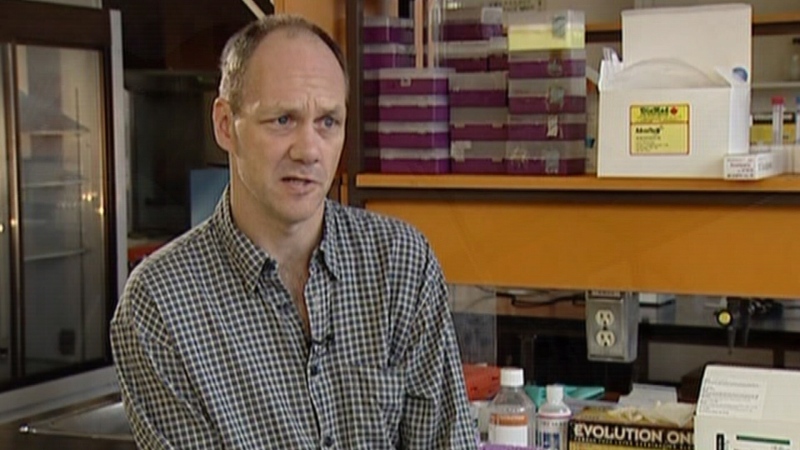

Vitamin D

In a preliminary study, University of Toronto researchers have found women with breast cancer who also have low levels of vitamin D had a greater chance of their cancer spreading.

Five-hundred women who were newly diagnosed with breast cancer were tested for vitamin D -- and only one in four had adequate amounts of the nutrient.

Those with low levels had a 94 per cent greater chance of their breast cancer spreading within 10 years -- and a 73 per cent increased risk of dying.

Screening embryos

And a woman in Britain conceived the first baby guaranteed to be free of the gene for hereditary breast cancer. Doctors are using the controversial testing -- called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis -- to screen embryos for certain diseases, including breast cancer.

The move is giving hope to families with a long history of diseases, like hereditary cancer, but some fear the practice could go too far -- using genetic selection for everything from beauty to intelligence.

In B.C., the survival rates of breast cancer are better than any other province in Canada.

We are now seeing the benefits of research where progress in the detection and treatment of the disease has reduced death rates by 30 per cent.

So that now one in every 100 Canadian women is a breast cancer survivor, we also know that breast cancer is not one disease but many diseases and that there is not one size fits all for treatment. The latest research is moving towards individualized care.

With a report from CTV British Columbia's Dr. Rhonda Low