A pilot project providing women with self-collection kits for cervical cancer screening is one part of a larger fight to eradicate the disease.

BC Women's Hospital is partnering with family doctors in Surrey and communities in northern B.C. to connect with women who may find it challenging to get routine screening done, according to Dr. Gina Ogilvie, the associate director of the Women's Health Research Institute.

"What we find in British Columbia is about 70 per cent of women are able to follow the recommended screening program, which is every three years, getting your Pap smear," Ogilvie said.

However, there are women who are not able to get regular screenings for a variety of reasons, and about 10 per cent of women have never been tested. Ogilvie said women may have diffculty accessing a doctor, or live in remote and rural areas.

The self-collection kit "allows us to the put the screening in the hands of women" she said.

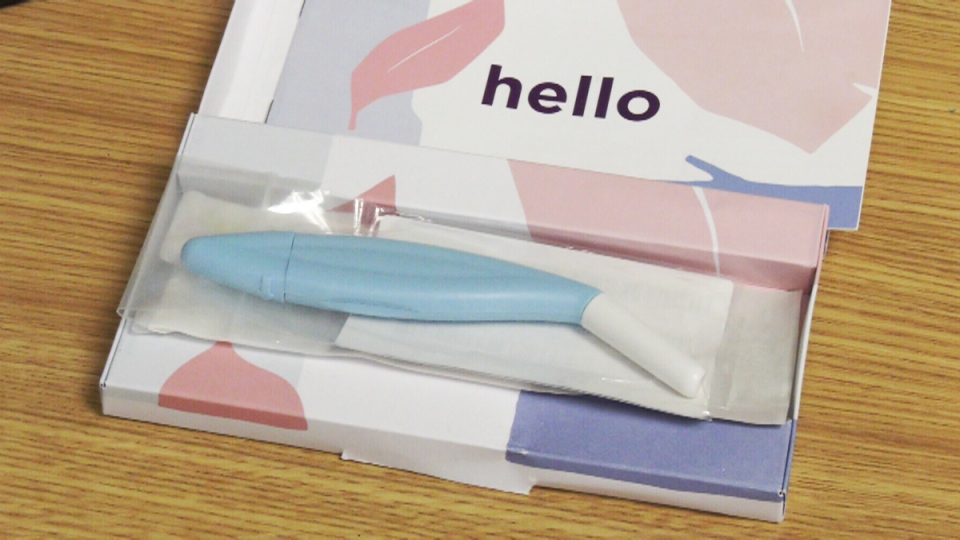

The kit comes in a small box, which could be mailed to the patient at home. It comes with a sampler device which is inserted vaginally to collect a swab. The device can then be put into a collection bag and sent back for testing.

"We wanted to see how it works, so it's not available broadly in the province yet," Ogilvie said.

She told CTV News Vancouver there is good data that shows a self-collected sample is as accurate at detecting the presence of the human papillomavirus (HPV) as a doctor-collected sample. HPV is the cause of the vast majority of cervical cancers.

"We have the tools to actually treat before it develops into cancer, and that's really important, and that's part of why we are so passionate about screening," Ogilvie said.

Every year in B.C., about 200 women develop cervical cancer, and around 55 die from the disease, according to Ogilvie.

"It's an entirely preventable cancer that impacts women in the prime of their lives," she said.

Jessica Peters was one of the B.C. women diagnosed last year. The 42-year-old mother of three from Chilliwack first began feeling ill in the summer of 2017, but says it took months for doctors to determine what was wrong.

"It didn't go away and my stomach was always upset," she said. "My periods got quite wonky and long, extremely long. Thirty days, that sort of thing."

Peters said as the months passed, she became more sick and more anemic. Finally in May 2018, she hemorrhaged following a biopsy and ended up in the emergency room, where she was told she had Stage 2B cervical cancer.

"It turned out that I had a five-centimetre tumour invading my perimetrial wall," Peters. "I never really thought that I was at risk for contracting HPV or having cervical cancer. I didn't realize it can lay dormant in your body for so long."

Peters underwent radiation including brachytherapy, which is internal, and chemotherapy. She documented her journey online, and encouraged women to get themselves screened.

"I can tell you from experience that a Pap smear is nothing compared to cervical cancer treatment."

Peters said before her diagnosis, she may have gone six or seven years without having a Pap test, which had always come back normal for her. She added two of her friends who went for Pap tests at her urging ended up having pre-cancerous cells removed.

"The sooner you can catch it the better."

Peters is now back at work, and her most recent scan showed no signs of cancer.

Along with screening, prevention is another critical tool. Ogilvie said HPV vaccine coverage is at about 65 to 70 per cent in B.C., but she'd like to see it higher.

"We have great data showing actually we are reducing those precancerous lesions already in the population of girls who receive the vaccine," she said. Ogilvie is also part of a team working on determining whether it may be possible to move from two doses to one, and still maintain effectiveness. The

BC Women's Hospital Foundation is hoping to raise $2 million towards Ogilvie's work.

Correction: The BC Women's Hospital Foundation said a doctor who spoke to CTV News was mistaken when she said 400 women develop cervical cancer in B.C. annually and 150 patients die. In fact, about 200 women develop the cancer in the province, and about 55 die.