The non-partisan watchdog tasked with uncovering problems in B.C.’s Ministry of Children and Family Development is providing so much oversight it's actually harmful, according to a new report.

Former deputy minister Bob Plecas was appointed to review the ministry earlier this year following a shocking case that saw staff return four children to their sexually abusive father.

In a copy of his report, which was released this week, Plecas calls for additional funding and more accountability in the ministry, but also suggests casting light on its failings has effectively created “greater instability.”

Blame is directed at both the media and Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, the Representative for Children and Youth who has helped uncover a plethora of problems since her position was created in 2007.

“Sadly, the relationship between the Representative and the Ministry has become strained,” Plecas wrote. “Persistent tension permeates everything that involves the two organizations that, at times, compromises their respective capacities to elevate the quality of service to which they are both committed.”

Plecas ultimately calls for the representative’s role to become one focused on advocacy, rather than criticism, and argues that oversight should be conducted within the ministry instead.

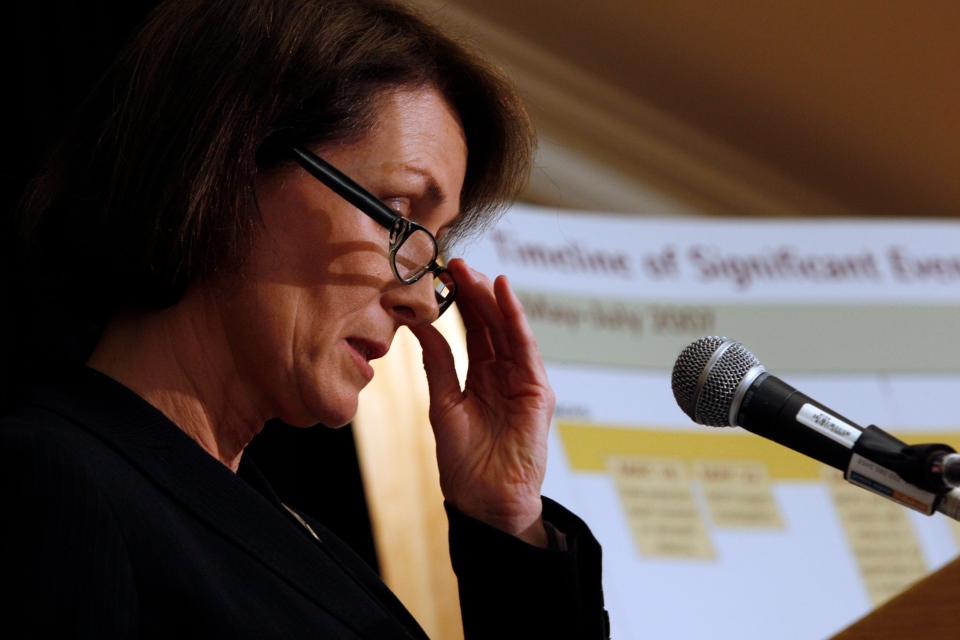

On Monday, Turpel-Lafond responded to the report by defending the work she’s done as children’s representative, pointing to her recent investigation into the death of Paige, an aboriginal teenager who overdosed after facing ongoing indifference from the government.

“Independent oversight of B.C.’s child welfare system remains a necessity,” Turpel-Lafond told CTV News in an email.

“In the absence of such public accountability, Paige’s story and the stories of other vulnerable children would never be told, leaving significant problems in the child protection system unaddressed.”

In his report, Plecas also recommends a term limit of six years for the province’s children’s representative.

Turpel-Lafond has been in the role since it was created, and is in approaching the end of her second five-year term.

Plecas argued the tragic cases uncovered by the children’s representative, including those that ended with children dying in government care, are rarer than the coverage they’ve generated would suggest, and that there should be more stories touting the successes in the ministry.

Plecas also said it would be impossible to prevent child-welfare tragedies, even fatal ones, from happening.

That point, in particular, did not sit well with Peter Lang, whose son Nick died days after entering a government-funded drug rehab earlier this year.

“You can’t run a ministry under that premise, that you’re just going to accept that you can’t save everybody. You’re doomed to fail if you do that,” Lang said.

He also said he has great respect for Turpel-Lafond, and believes outside criticism is the last thing stopping the government from providing better care and support for families.

“She’s been telling them for years what the issues in the ministry are and they haven’t done a darn thing. So one of their buddies comes along and says the failings of MCFD are due to too much criticism? That’s just a joke in my opinion,” he said.

In his report, Plecas highlights a number of serious issues facing the ministry, including a lack of effective training, the erosion of program dollars, trouble recruiting and retaining front-line staff, and a lack of effective performance assessment.

“Currently, the child welfare system does not have a rigorous performance appraisal system in place, and does not define what good practice and good performance are in terms of expectations for outputs or outcomes,” it reads.

Plecas suggested giving the ministry two years to institute a quality assurance, audit and complaints process. He said the children’s representative should continue in its current capacity until its ready to transfer its oversight role.

The ministry serves more than 155,000 children and their families every year, with just 4,476 employees. Its budget this year is nearly $1.4 billion.

With a report from CTV Vancouver’s Jon Woodward