VANCOUVER -- British Columbia has one of the country's toughest drunk driving laws, but if drivers choose to challenge a roadside ban and the penalties and fines that come with it, they have at least a one-in-five chance of getting it tossed out.

Last year, the government amended the impaired driving legislation that was introduced in 2010. The changes were aimed at bringing the law into compliance with a court ruling that concluded those accused of drunk driving had their rights violated due to their inability to challenge roadside screening tests, and to the lack of a proper appeal mechanism.

The Office of the Superintendent of Motor Vehicles says in the year since the amendments, about 22 per cent of the 2,708 drivers who challenged an immediate roadside prohibition got it overturned. A total of 18,888 driving bans were issued in that time period.

While some defence lawyers applaud the successes, they say the appeal process remains unfair because it takes place outside of the court system.

"We're happy for our clients when we succeed, and it's certainly nicer to be able to call people to tell them they'd won," said Vancouver lawyer Paul Doroshenko.

"But the tribunal system does not allow you to really get to the bottom of it, and there are lots of innocent people who end up stuck with (the roadside bans)."

Having all appeals take place within the courts would likely lead to immense backlogs, as 6,027 out of 49,000 roadside prohibitions have been challenged since the law came into effect in 2010.

"It's new legislation, it's innovative legislation, of course people are going to take pokes at it," Justice Minister Suzanne Anton said Wednesday. "But fundamentally, the legislation is very good, it's been extremely effective in keeping people who are drinking out from behind the wheels of their cars."

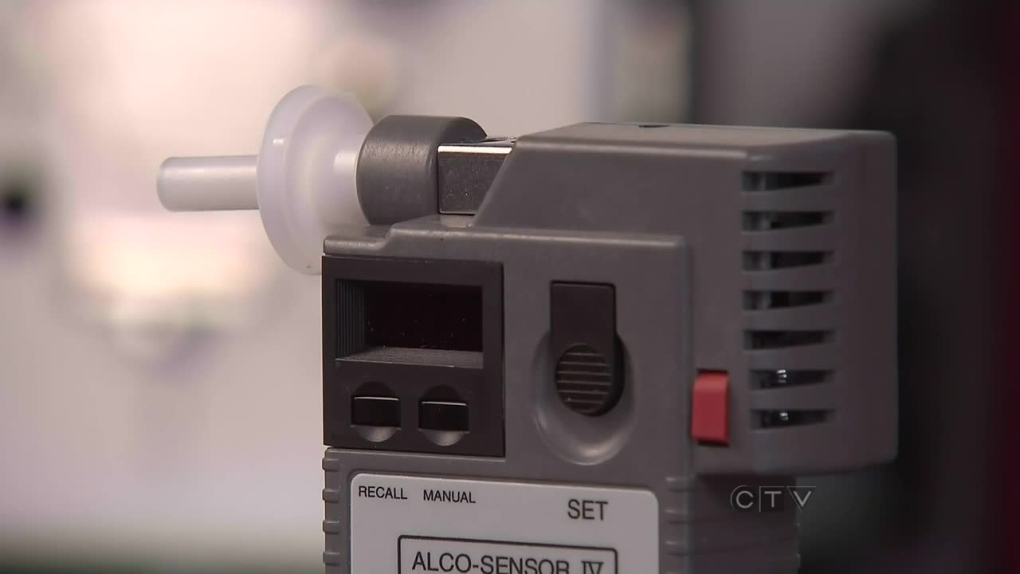

The amended law requires police to tell drivers they can have a second test on a different breathalyzer if they fail the first one. In the past, the second reading would prevail, but now the lower of the two readings will.

Officers must also now provide sworn reports to the Superintendent of Motor Vehicles for every roadside prohibition issued, as well as certificates that confirm the calibration accuracy of the breathalyzers they use.

Drivers who fail both screening tests will have their vehicle towed and their license taken away immediately. They have seven days to apply for an appeal, and an oral review, done over the phone, usually happens within three weeks.

After the 30-minute review, an adjudicator makes a decision based on any statements or evidence that the driver presents, as well as any documents or information provided by the police officer who issued the ban.

Some lawyers say seemingly innocent people frequently have their evidence rejected, while others who may be guilty get let off on a technicality.

Earlier this week, a B.C. Supreme Court judge ruled that a roadside ban upheld by a government adjudicator in March should be quashed. A government report on approved screening devices used by the adjudicator to make her decision was inadmissible because it wasn't entered as evidence -- the adjudicator simply referred to it of her own accord, said the ruling.

Sam MacLeod, B.C.'s superintendent of motor vehicles, has said his office is looking into the court's decision, but will need time to decide how to move forward.

Criminal defence lawyer Jennifer Currie says the process for sorting out the innocent from the guilty is flawed because there is no opportunity to cross-examine the police officer who issued the ban, or witnesses.

"Somebody can say, 'I saw this person do this,' and in court, we can go up, and we can ask questions about how far away they were, how good of a look they really got, how long they saw it, could they have mistaken them for somebody else?" she said. "You can't do any of that for one of these."

But MacLeod stressed that a roadside prohibition review is an administrative process, and not a criminal proceeding. During the review, defence lawyers do get a chance to examine the evidence that the police officer provided, he said.

"The driver who's asked for the review gets to see everything the police have put forward to us," he said. "So when they are in a discussion with the adjudicator, they can comment on exactly what the police have put forward."

However, drivers cannot obtain more evidence from a police officer -- such as video recordings from a police cruiser, or records of the screening devices used -- beyond what he or she has given to the adjudicator unless the driver files a freedom of information request, said Doroshenko.

"You don't know, for example, that the device was manufactured and came back with a flaw...and you don't know that the police officer may have been disciplined for lying in reports before," he said. "In criminal court, they'll take as long as necessary to get to the bottom of it, but in these hearings, you've basically got 29 minutes to make your pitch."

Critics of the roadside screening devices have also long argued they are too finicky for such tough, immediate penalties.

Currie has had clients -- some more credible than others, she admitted -- who swear they had a drink hours before they were pulled over, yet they still failed the tests.

"In those situations it's almost impossible to win," she said. "At the end of the day, the adjudicator is going to decide, 'You blew a fail in a properly serviced, properly calibrated screening device, and I don't find your submission that you consumed these drinks five hours earlier credible."'

Yet it is possible that the device, which must be recalibrated every 28 days, was inaccurate, despite what its certificate says, Currie said.

"The calibration can go off halfway through the cycle, and then you're using an improperly calibrated device and you can easily be getting these false readings," she said.

The devices also do not distinguish between mouth alcohol or blood alcohol, she said.

But MacLeod stands behind the breathalyzers, which were initially meant to be a screening test to determine whether a driver should be taken to a police station to take a more thorough test on a more advanced machine.

"They've been used for many, many years, they are federally mandated and federally approved," he said. "All told, it's a scientifically-approved instrument."

The costs associated with failing two roadside tests can add up to thousands of dollars for a driver who chooses not to challenge a roadside ban -- which, MacLeod pointed out, has resulted in a 51 per cent-reduction in drunk driving fatalities since the law was introduced in 2010.

An oral review costs $200, and while the towing and storage fees will be waived or refunded if the driving ban gets overturned, the driver has already suffered consequences, said Doroshenko.

"Even if you're innocent, you've already been punished," he said. "Even the people who manage to get their (prohibitions) overturned have already had three weeks, usually, of no license, no car, and potentially a job loss and whatever else flows from it."