VANCOUVER -- Canadian health officials are being lobbied to use smartphone technology to help track and control the spread of COVID-19.

Singapore and South Korea have done it -- with mixed results --and now a B.C./Silicon Valley based company called LivNao is urging health officials to use the technology here.

“We can easily trace exactly who a positive case had contact with, when and where and how much of a contact they had,” said Daniel Leung, LivNao Technologies CEO.

In Singapore, the government developed and launched an app called TraceTogether. It went into operation on March 20 and so far, about one million people have signed up. The government says it does not use GPS or location data of any kind. It only seeks to establish who else might have been exposed to the virus by exchanging short-distance Bluetooth signals between phones of others users who are in close proximity.

LivNao's Technologies says its app uses both Bluetooth-enabled technology and GPS to track cases and any contacts they may have. The app fills in all the memory gaps a positive COVID-19 patient may have, and speeds up the contact tracing process.

LivNao Technologies says unlike TraceTogether, its app can go back in time after a user signs up to identify past contacts.

“We basically do that in less than a second using technology that already exists,” said Leung.

Right now, in Canada, contact tracing is done manually and it takes time and money.

“We’re getting additional help from med students to literally pick up the phone and call all these patients,” said Toronto physician Dr. Cathy Zhang.

She’s the vice-president of the Canadian Association of Physician Innovators and Entrepreneurs, and is on board with the idea of smartphone tracing.

“Medicine and health care in general - we’re very behind in technology,” she said. “That is what the health-care systems, from a clinical standpoint, need.”

But privacy experts are not as quick to embrace the idea.

“What we have to be mindful of is who might get their hands on this stuff,” said Meghan McDermott, staff counsel for the B.C. Civil Liberties Association. “When you have a state actor and a private actor, things can get murky very, very quickly.”

Because LivNao has offices in both Silicon Valley and Vancouver, McDermott said it would be subject to two different sets of privacy regulations.

Leung said the collected data is anonymized, meaning it doesn’t link a person with their information unless a user gives permissions to do that. He says the company is HIPPA compliant in the U.S. to protect health information and privacy.

LivNao has reached out to health officials in B.C., Alberta, PEI and Ontario and says it’s getting the most traction in Ontario. The company also says the technology should be adopted quickly in order to stay ahead and flatten the curve of positive cases.

“Yes, this could be an amazing tool, but I don’t think it’s the kind of tool that we should just come out and push our government to adopt in a matter of days, hours or weeks,” said McDermott.

Lives hang in the balance and while it’s difficult to weigh the concerns of a public health emergency against privacy rights, there’s concern adopting such technology could be a Trojan horse, unless it’s thought through properly.

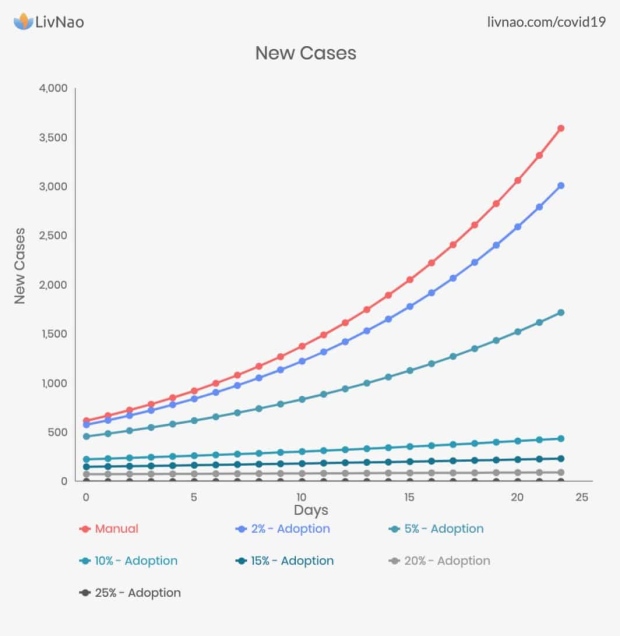

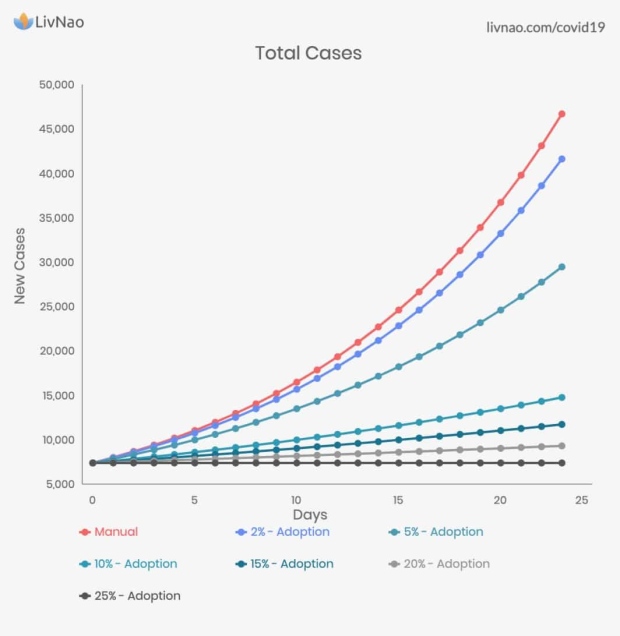

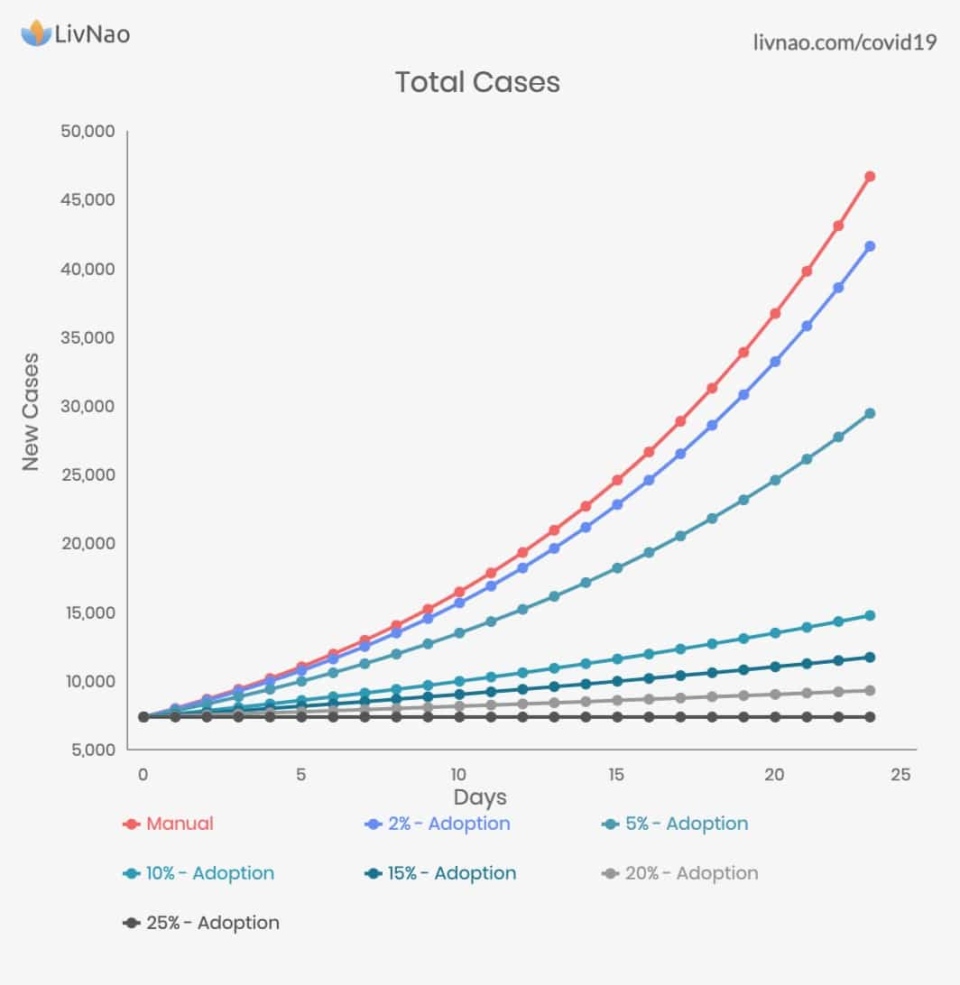

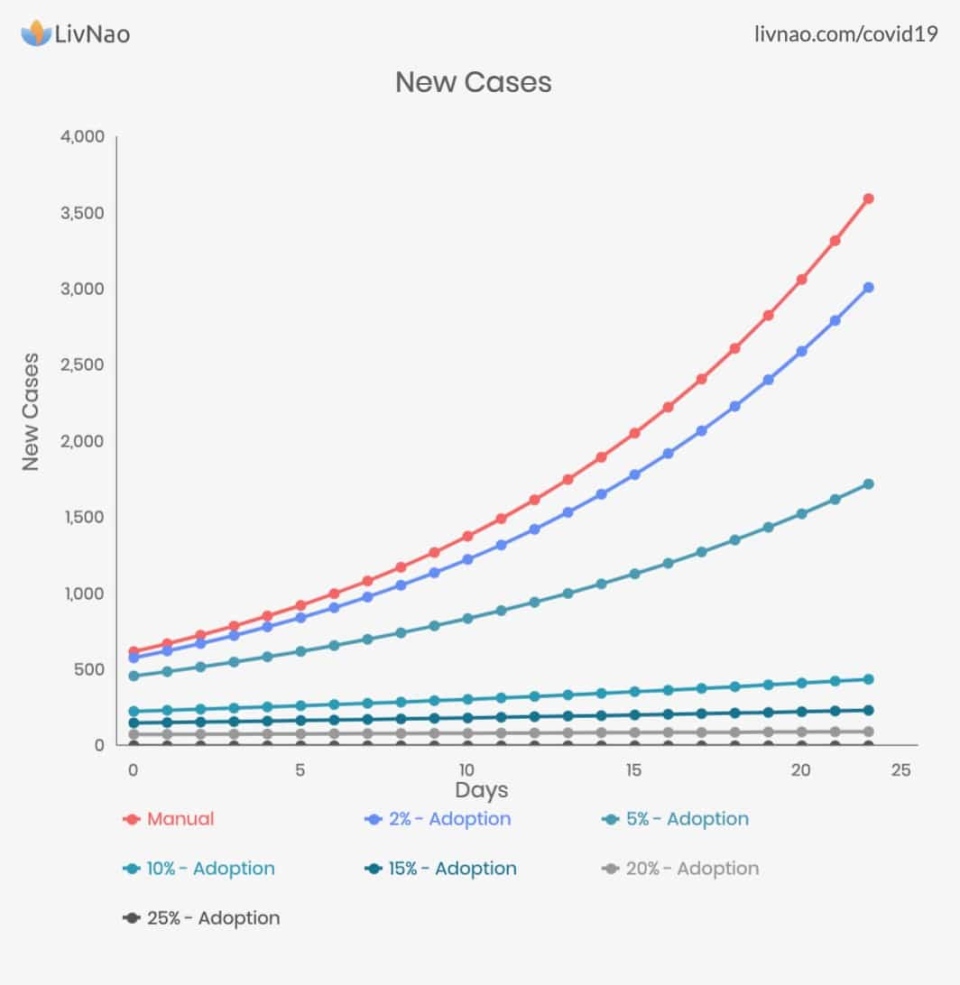

LivNao did modelling based on a study by Oxford study to calculate the impact of digital contact tracing on flattening the curve.