Frontline workers in the opioid crisis are sounding the alarm over a new type of overdose happening on Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside that leaves drug users unconscious for hours, even if they’ve received a shot of naloxone to reverse the effects of the opioids in their system.

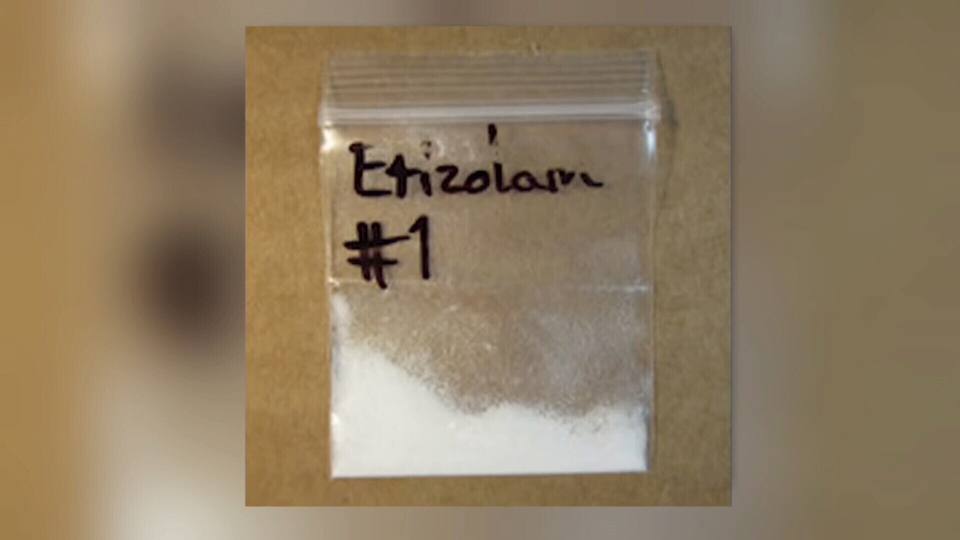

Vancouver Coastal Health has confirmed some drug samples sent to Health Canada for testing have come back positive for etizolam, a powerful sedative used to treat anxiety and sleep disorders.

“Normally, if you give someone Narcan, they would bounce back with a little bit of oxygen, but now people are just sort of staying down,” said Sarah Blythe, executive director of the Overdose Prevention Society.

Blythe said she and her staff first noticed the problem at their supervised consumption site a few weeks ago and more than two dozen people have overdosed there in this way since.

Once nalaxone is administered to the patients, they begin breathing on their own again, but remain unconscious for several hours with extremely slow respiration and heartrates.

“A lot of these people don’t come back for a few hours. They’re being watched in these overdose prevention sites for somewhere up to three or four hours before coming back,” said Ryan Vena, founder of Street Saviours, a group that patrols the Downtown Eastside to help overdose victims, “and then they’re confused. They don’t know what’s happened. Half the day’s gone and they’re going, ‘What happened?’”

Both Blythe and Vena say this is just another example of drug dealers cutting their supply with whatever they have on hand in order to maximize profits.

It is etizolam now, but it could be something else even more dangerous next week.

"That brings it back to the stigma behind it and that unsafe drug supply, right?” said Vena. “So, people not able to access a clean drug supply, you don't know what you're getting. It's not safe anymore."

They would like to see a government-regulated opioid supply for addicts that would replace the drug dealers and the dangerous cocktails of unknown substances they sell on the streets.

“They would know what it is. They know what dose they’re taking. They’re not going to overdose,” said Blythe. “We’re not going to have to wonder what they took and find out later on after they’ve overdosed and gone to the hospital.”