VANCOUVER -- An international team of researchers used data from seismic stations in 117 countries to determine that restrictions aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 led to an unprecedented drop in noise.

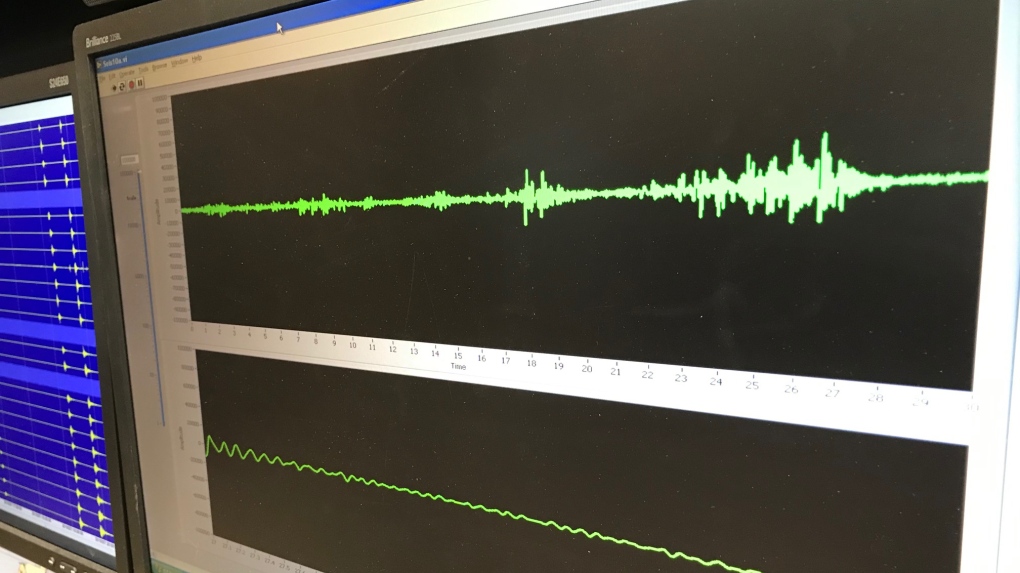

The study published Thursday in the journal Science shows seismic noise, or vibrations generated by human activity, dropped by as much as 50 per cent in March and April, particularly in urban areas.

Mika McKinnon, one of the study's authors, said they've dubbed this quiet period the “anthropause,” as traffic, planes, cruise ships, conventions, concerts and sports games slowed or stopped.

“We could actually see very sharp cut off starting in China and Italy and then everywhere else as the pandemic spread and the policies and the lockdown spread,” said McKinnon, who teaches in the department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences at the University of British Columbia.

And while it was most pronounced in cities, McKinnon said the sound of silence could also be seen in data from an abandoned mine shaft in Germany that's one of the quietest places on Earth.

A seismic station in Vancouver showed noise levels plummeted when the province closed schools, followed by bars, restaurants and other establishments, she said.

In nearby Seattle, seismic noise dropped later and returned sooner, she added.

“There is a different amount of background noise to start with. But if you look at the percentage decrease, people in Vancouver stayed at home much faster,” said McKinnon.

As the pandemic wears on, she said data from the quiet period will help scientists detect more earthquakes and allow them to better differentiate between human-caused and natural seismic noises.

“We're getting a much better understanding of what these human-generated wave shapes are, which is going to make it easier in the future to be able to filter them back out again.”

McKinnon said the latest data won't help predict if and when earthquakes will hit, but it does offer scientists deeper insight into the planet's seismology and volcanic activity.

The seismic data is also reassuring, she said, because it shows many people are still making less noise while sticking closer to home and following public health guidelines during the pandemic.

The drop in noise is being measured in Earth's oceans as well, said Richard Dewey, associate director of science at Ocean Networks Canada, based at the University of Victoria.

He likened the pandemic to an unplanned experiment for marine acoustic researchers who have been hoping for years for an opportunity to study the ocean without noise pollution from massive tankers, cruise ships, ferries, whale-watching and commercial-fishing vessels.

So far, data from two monitoring sites off the coast of Vancouver Island shows underwater noise dropped week by week, particlarly in April, as economic activity slowed down, said Dewey.

A quieter ocean is part of the formula that would help the recovery of endangered southern resident killer whales, which return each year to the Salish Sea around southern Vancouver Island, he said.

It's a tall task to assess whether the orcas' behaviour has changed in response to the drop in noise, said Dewey, since their calls are unique, and researchers only hear snippets when the southern residents travel past hydrophones that record them.

“We have a pod going by and sometimes you just hear a single whale vocalizing ... and sometimes they're all chatting at the same time. We don't necessarily know how to interpret that.”

But the general hypothesis is that if the ocean were quieter, the whales could communicate with each other, navigate and assess their environment and acquire food more effectively, said Dewey.

He said researchers will look at data from before, during and after this quiet period to see if they can make distinctions between the meaning, frequency and density of the orcas' calls.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 23, 2020.