VANCOUVER -- As British Columbia records its highest single-day case count in two months, the province is second only to Saskatchewan in new infections per capita over the past two weeks. Experts are warning more must be done soon, especially with thousands of people facing long-term symptoms.

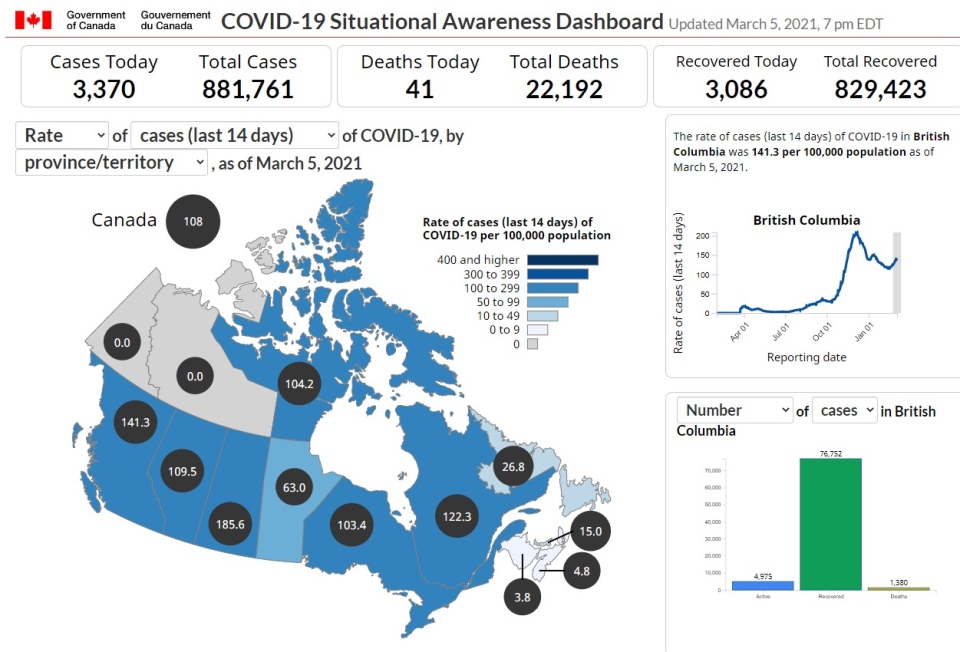

On Friday, B.C. health officials announced 634 confirmed cases of COVID-19. A federal infobase shows B.C. infections at a rate of 141 per 100,000 residents when averaged over the past two weeks. Saskatchewan posted 186 per 100,000 residents, while the national average was just 108. And, while the majority of provinces showed a continued decline or flattening of infections, only the westernmost province showed significant growth.

"Obviously what we’re doing in British Columbia is not having the desired effect. We cannot have 650 cases a day and we cannot tolerate it until the vaccine kicks in and produces community-based immunity, we’re weeks and months away from that,” said Dr. Brian Conway, president of the Vancouver Infectious Disease Centre.

“All of this is suggestive of less-controlled, if not uncontrolled, community-based (rather than institutional) spread and this is the part of the pandemic that is of most concern,” Conway said. “If that occurs, then we need to intervene in a way that is different from what we are doing now to control (it).”

Only a handful of long-term care and assisted-living facilities declared outbreaks in February, and there haven’t been any in March so far.

While vaccine availability is ramping up and the number of deaths continues to decline, one of the experts on the front line is warning those numbers tell only part of the story.

Many thousands of "long COVID" cases in B.C.

As the months wear on, more and more people are reporting COVID-19 symptoms that persist well beyond their infectious period. Medical professionals treating them at three specialty clinics in Metro Vancouver say B.C. statistics mirror what other countries are observing.

"We don't know what the absolute prevalence of the ‘long COVID’ disease is now, but we know from the data 75 per cent of hospitalized patients are having ongoing symptoms at 3 months,” said Dr. Zachary Schwartz, who leads the Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic at Vancouver General Hospital.

“For outpatients, probably upwards of 30 per cent of people can be still symptomatic at 6 months or 9 months after their infection.”

There isn’t a definition yet of what would qualify someone as a “long-hauler.” Symptoms can be mild to severe and range from tightness or pain in the chest to coughing and trouble breathing. Concussion-like symptoms – such as brain fog and fatigue – and mental health problems have also been reported.

"We do have psychiatrists involved in our networks that are seeing individuals relatively rapidly because we're seeing both a new onset of mental health disorders like PTSD, anxiety, depression and – in people who have previously been diagnosed – we're definitely seeing decompensation in some of their mental health as well," he said.

In Surrey, they’ve only seen 18 patients at the Post-COVID-19 Recovery Clinic at Jim Pattison Outpatient and Surgery Centre, which opened Jan. 8.

A total of 130 patients have been accepted at VGH, where applications are now open for referrals.

St. Paul’s Hospital has provided the lion’s share of the treatment, with 328 seen by doctors. Providence Health says the hospital is “building capacity both virtually and actually.”

With limited space, patients need a referral for treatment and the facilities are currently only accepting the most severe long-haulers. For those with mild to moderate symptoms, they’re increasingly providing online resources for them to manage their symptoms.

Warnings from doctors as complacency becomes more common

As the weather warms up and pandemic fatigue has people desperate for company, Conway believes more targeted restrictions may be needed to avoid disaster.

“I’m hoping it’ll be the Whistler approach,” he said, noting that targeted business closures, emphasizing household bubbles and some changes to living situations slashed transmissions by 75 per cent in a month.

"My sense is, what's going on in Surrey and the surrounding areas in the Fraser Valley is community-based transmission is occurring, so either it's living situations that need to be changed or people are making decisions in their day-to-day lives that ‘this one time, this one evening, it's OK to not follow the rules.’"

Conway praised public health officials in other provinces who moderated restrictions based on infections and allowed communities with few cases to carry on, while hotspots in Toronto and Montreal saw crackdowns that brought transmission under control.

“Broad restrictions (in B.C.) are probably not appropriate and people wouldn’t necessarily follow them anyway, they would be resistant, so I think a targeted approach is where we need to pay attention,” he suggested.

With 76,752 people who tested positive for the disease have now classified as “recovered,” Schwartz said it may be more accurate to call them “recovered from acute disease” or “no longer contagious,” since a third of them could still be experiencing symptoms; that’s roughly 25,000 people who could be feeling a faint tightness in the chest, or struggling to get out of bed.

“You don't want to end up with these symptoms long-term because they're debilitating … people who cannot get back to school full time, people who cannot get back to work full time," he said, noting that aside from the personal and family toll that’s taking, it’ll increasingly have an impact on our economy and health-care system.

“When you apply that to a population health level, when you apply that to 500 cases a day just to British Columbia, it starts becoming significant," Schwartz said.