VANCOUVER -- British Columbia's New Democrats are dazed and confused today, pondering a stunning election defeat that saw Premier Christy Clark's Liberals capture a majority despite pollsters reporting the NDP leading the campaign from start to finish by as much as 20 points.

New Democrats, some in tears, others jaws gapping and walking around as if hit by a speeding truck, could only suggest their decision to run a campaign free of personal attacks needs a second look: Nice guys, it appears to them, do finish last.

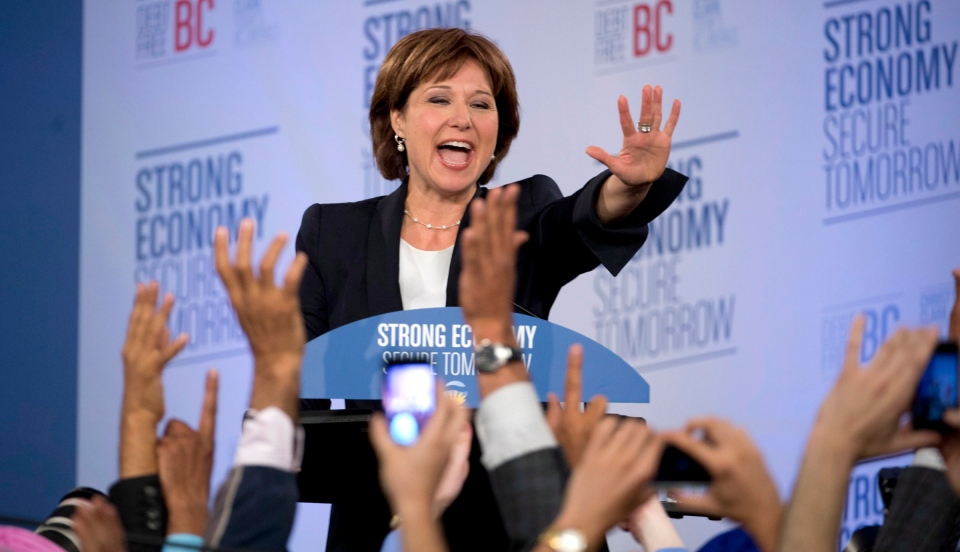

Pollsters had tracked the election as a guaranteed win for Adrian Dix's New Democrats throughout the campaign, but Clark's Liberals defied the claims of NDP momentum and lowly polling numbers to win a majority government Tuesday, posting a stunning turnaround for a party and a premier written off for dead when the election started just a few weeks ago.

"The polling clearly doesn't reflect what we're seeing tonight, so I guess that raises some questions about that," said New Democrat Shane Simpson, the NDP Opposition caucus chairman, suggesting the NDP's internal numbers pointed to a tight race, but the public numbers raised expectations of an NDP rout.

Simpson said the election result, which now relegates the NDP to Opposition status for another four years, means the party must re-evalutate its election strategy that focused on policy, programs and issues and steered clear of the well-tested B.C. tradition of pounding the policies and personalities of the opponents to political pulp.

"We tried to elevate politics," said Simpson. "We tried to take a lot of the personal negativity out of it. I think that was the right thing to do. I feel very positive about our choice to do that."

But feeling positive didn't win them the election and that needs to be confronted, he said.

"The issue, now of course, will be having to do some assessment of how that played versus the Liberals' choice to drive a very negative campaign."

At a news conference following his election concession speech, Dix defended his positive politics campaign, saying it was a way to bring young people back to politics and keep them coming back because of their interest in issues rather than personal attacks.

"Obviously, the Liberal Party takes a different approach," he said. "But for us, this is obviously a serious defeat. We're obviously going to meet as a party and assess that."

When asked about his future, Dix said the party will be spending days, weeks and months considering the election and how to move forward.

The vote saw the Liberals increase their standings in the legislature, winning 55 ridings to the NDP's 33. The Greens elected one MLA.

Former B.C. NDP finance minister Paul Ramsey said Clark proved to be a formidable campaigner and she deserves much of the credit for the Liberal turnaround.

"She took a party which was -- at best -- lukewarm towards her, very few of the caucus supported her," said Ramsey at an NDP campaign gathering in Victoria. "Many of the senior ministers chose not to run in this election under her leadership. In spite of that she carried on, put together a good election team, performed well during the debate and obviously around the province."

Ramsey said Clark had British Columbians pondering economic development that was set to occur years down the road in the form of liquefied natural gas exports, but said little about her current plans to improve education, health and child poverty.

She also focused on Dix's infamous decision to back-date a memo to help former NDP premier Glen Clark escape scrutiny from a gambling development scandal that eventually forced him to resign.

Dix was fired from his job as Clark's chief of staff after admitting he changed the memo.

It also didn't help Dix to have Clark constantly mention the dismal economic record of the two NDP governments of the 1990s.

But even though Dix and the New Democrats said the Liberals were running a negative, attack-style campaign, Liberal advisers said Clark's real knockout punch was delivered through her consistent message that British Columbians want a government that makes a strong, stable economy its top priority.

"We were seeing that wherever the premier went, people felt confidence," said Stockwell Day, a former federal Conservative cabinet minister who has been working with Clark as an adviser. "The sense was, and she believed this: If she could get out there unfiltered and she could get her message out that economic prosperity is what people are going to be banking on, that that would carry the day."

Former Liberal cabinet minister George Abbott said public opinion started to shift in favour of Clark and the Liberals when Dix said early in the campaign that an NDP government did not favour oil pipeline expansion in B.C., including the proposed Kinder Morgan project that would bring oil tankers into Vancouver's port.

"If there was one thing that started to move public opinion, and started to firm up the B.C. Liberal base, it would have been the reversal on Kinder Morgan," said Abbott, now a University of Victoria lecturer. "I think that had some messages for the business-investment community, which had the effect of both undermining Conservative support and strengthening the BC Liberal base."

But a University of B.C. political expert said Clark's economic focus was only part of her success, because going negative often produces positive results.

"We know that when politicians go negative, it has an impact because people listen to bad news," said Max Cameron. "I think we're actually kind of hard-wired to watch for danger in our environment, so if someone says this person is unreliable, be careful, you pay a lot more attention than if they say this person is a great person, this is someone you can trust. That's a normal part of politics."