B.C. landscapes may never recover from wildfire damage, ecologists say

The Okanagan’s hills are unrecognizable in the wake of the devastating wildfires in the region.

The scorched hectares are now visible in places like Kelowna as the smoke clears, and tall trees that once filled the landscape are gone and replaced with ash.

Wildland fire ecologist Robert Gray has been assessing the wildfire damage in the province and believes the trees that once stood tall in some areas may never return.

"Trees established there a century ago under slightly different climate, and it's only going to get drier, so we wouldn't expect trees to establish there very well," said Gray.

"If they do, they're not going to grow very fast and it's likely going to be a lot of shrubs, grasses and herbs on that landscape and not a lot of trees."

Gray says the scorched land can germinate low plants, and he expects there will be an abundance in the future that will dominate the landscape.

He explained that the current landscape in parts of the province, especially in the Kelowna area, is shifting but without control— forcing officials to be in response mode.

"Having small patches of high-severity fires is great. It's actually quite beneficial for (bio)diversity, but we want to be more in the driver's seat," said Gray.

The wildfires burning in B.C. this year have torn through a record two million hectares, according to recent estimates.

Burned trees are seen on hills in the Okanagan post-wildfire. The fires have threatened the homes of thousands of people and the local wildfire that shares them.

Burned trees are seen on hills in the Okanagan post-wildfire. The fires have threatened the homes of thousands of people and the local wildfire that shares them.

Adam Ford, a biology professor at University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus, has been tracking dozens of wildlife throughout the summer and has witnessed their movements as the wildfires encroached on their habitats.

"Some of these fires can burn really hot, and they can burn right through mineral soil, in which case it'll be a long time before vegetation comes back," said Ford.

"But typically, when we think of fires not being a bad thing, it's because it clears out some shrubs. It opens up sight lines, it brings back a flush of nutrients to the understory plants."

Ford explained that mule deer are an example of a species that can thrive post-wildfires, and they've been observed returning to their homes hours after fires have ripped through.

Where the issue lies is if they can't avoid rapidly expanding blazes and are killed as a result.

Forester and UBC Ph.D. student Ira Sutherland has been studying wildfires in the province for many years and has devoted the past two and a half to dissecting B.C.'s forest management history.

His research dives into the systemic historical dynamics that are preventing land management institutions in B.C. from adapting or transforming as needed to tackle emerging environmental challenges such as increasing wildfires.

The study explains how forest management institutions have successfully adapted in the past, but long after the problem was recognized.

"It's like when you get in a dark alley, what you do is you put your head down and keep walking, but now we've lifted our head up and are looking for solutions," said Sutherland.

Sutherland outlines three recommendations: managing forests more locally, restoring complex landscapes and using reflective processes to help transform institutions to meet emerging landscape challenges.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

What is whooping cough and should Canadians be concerned as Europe declares outbreak?

There is currently a whooping cough epidemic in Europe, with 10 times as many cases compared to the previous two years. While an outbreak has not been declared nationwide in Canada, whooping cough is regularly detected in the country.

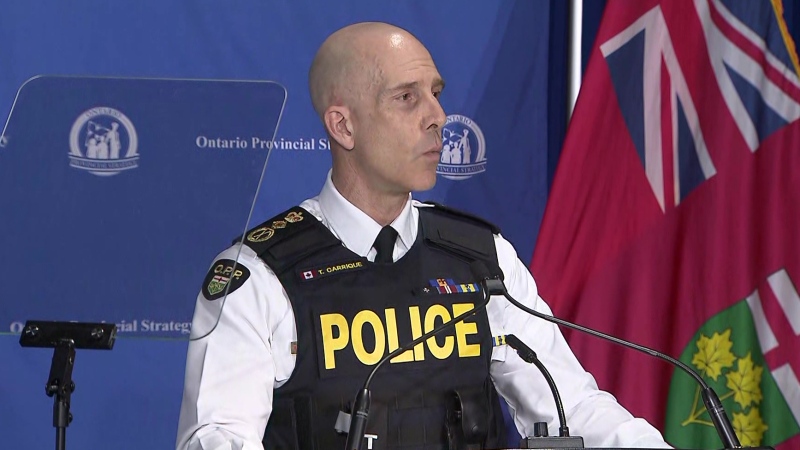

Ontario Provincial Police arrest 64 suspects in child sexual exploitation investigation

Ontario Provincial Police say 64 suspects are facing a combined 348 charges in connection with a series of child sexual exploitation investigations that spanned the province.

AstraZeneca says it will withdraw COVID-19 vaccine globally as demand dips

AstraZeneca said on Tuesday it had initiated the worldwide withdrawal of its COVID-19 vaccine due to a 'surplus of available updated vaccines' since the pandemic.

'Summer of discontent': Federal unions vow to fight new 3-day a week office mandate

Federal unions are launching legal challenges and encouraging public sector workers to file "tens of thousands" of grievances over the new mandate requiring federal workers to return to the office at least three days a week in the fall.

Toronto police seek suspect vehicle after security guard shot outside Drake's mansion

Toronto police are seeking help from the public as they continue to investigate a shooting that seriously injured a security guard outside rapper Drake's mansion.

'Ozempic babies': Reports of surprise pregnancies raise new questions about weight loss drugs

Numerous women have shared stories of 'Ozempic babies' on social media. But the joy some experience in discovering pregnancies may come with anxiety about the unknowns.

OPINION What King Charles' schedule being too 'full' to accommodate son suggests

Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, has made headlines with his recent arrival in the U.K., this time to celebrate all things Invictus. But upon the prince landing in the U.K., we have already had confirmation that King Charles III won't have time to see his youngest son during his brief visit.

Seafood, eat food: Calgary Stampede releases Midway menu

The Calgary Stampede has released its menu of sweet, salty and spicy treats available on the Midway for the Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth.

Boy Scouts of America is rebranding. Here's why they've changed their name

After more than a century, Boy Scouts of America is rebranding as Scouting America, another major shakeup for an organization that once proudly resisted change.