VANCOUVER -- As Canada’s top doctor warned the country about a third wave of COVID-19 driven by variants and researchers urged governments to ramp up testing, B.C. health officials are downplaying the predictions and defending the province’s approach to testing and variants.

Canada’s chief public health officer Dr. Theresa Tam cautioned that with more-contagious COVID-19 variants now spreading in all provinces, “the current community-based public health measures will be insufficient to control rapid growth and resurgence is forecast.”

That resurgence could lead to a seven-fold increase in daily infections, according to modelling Tam presented in Ottawa.

During her briefing in Vancouver on Friday, B.C.’s deputy provincial health officer Reka Gustafson responded to questions about Tam’s modelling.

“Mathematical models are exactly that, and they take the parameters that we are seeing with these new variants and can give us potential scenarios,” Gustafson said. “They don't predict what's going to happen, and I think that's really important to remember.”

“There is actually no indication from the behavior of the variants that we need to do anything that is different, and what we mean by that is that the mode of transmission of the new variants is very similar, the virus is just more efficient (in its) transmission … The things that we need to do to prevent the transmission of variants are the exact same things we do to prevent COVID-19, but we have less room for error.”

Tam and other experts have been taking a more aggressive tone in warning citizens that the mutations that make the virus more contagious and deadly can spread with alarming speed, as seen in Newfoundland and Labrador this month, requiring both careful monitoring and a willingness to make amendments to public health orders.

Adding further concern to the situation, a team of B.C. university researchers is urging governments to swiftly ramp up detection of the variants, lest they spread undetected.

“I’m very concerned about the higher transmissibility of these variants — we’re going to hit a wall in Canada when these variants start circulating in the community and we’re going to have to see much more strict regulations to bend the curve down with such a rapidly growing variant,” said UBC biomathematician and study co-author Sally Otto.

“We constructed a model that would predict by the time you find your first case, how many other cases would there be in the community? And the thing is, if we don’t look at a lot of cases, if we don’t do a lot of sequencing, there could be hundreds of cases by the time we detect a case in the community.”

B.C. was one of the first provinces to adopt a more efficient process for screening for variants, which is much more complex and time-consuming than a standard COVID-19 test, which provides a response within 24 to 48 hours.

Only after someone tests positive are specially selected samples sent to a B.C. Centre for Disease Control lab – one of only a handful in the country capable of further testing – for targeted PCR testing to search for a mutation the three main variants of concern have in common. If the mutation is detected, then full genome sequencing is done to determine which variant in particular has been discovered; the process takes almost a week.

“In order to really find it when it’s one or a few people, before it gets out and established within the community, we have to ramp up that testing pretty much every week or every other week,” Otto said.

That suggestion comes as B.C. testing rates remain relatively stagnant. While the health minister and provincial health officer had promised a capacity for 20,000 tests per day by the fall, actual tests have never come near that. The most tests performed in a single day was 15,213 on Nov. 27, around the height of the province’s second wave. Since then, daily tests have been largely under the 8,000 mark.

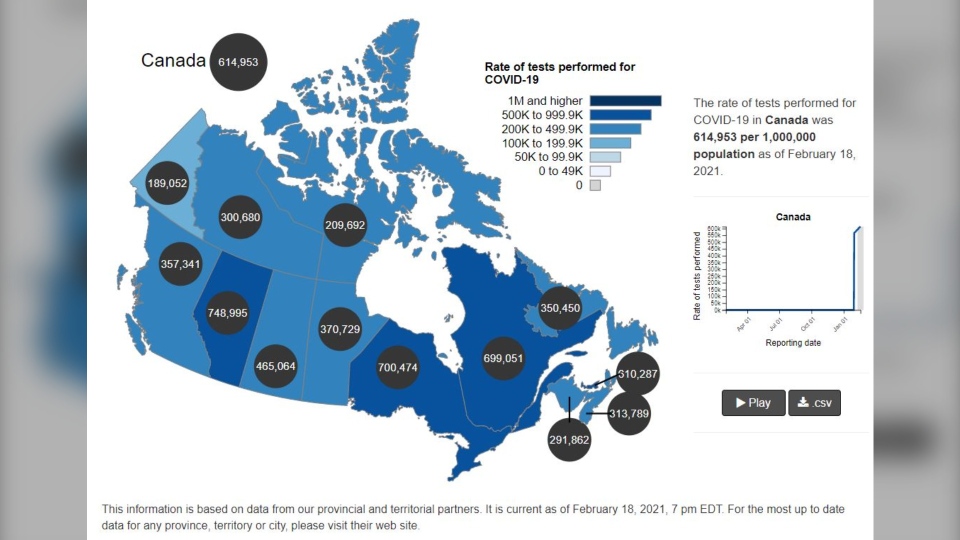

On a national scale, B.C. is also well behind on testing, especially compared to the other most populous provinces on a per capita basis. Canada-wide, there have been 614,953 tests for every million residents, but B.C. has only conducted 357,341 per million. Alberta is at 748,995 while Ontario and Quebec are virtually tied around 700,000.

CTV News asked Gustafson if the province had any plans to ramp up testing or change the criteria, which were made stricter in December and require specific or persistent symptoms for testing.

“Our testing guidelines in British Columbia have actually quite a low threshold,” Gustafson said. “We actually have no indication that we're missing large numbers of cases or even substantial number of cases.”

“One of the reasons may be that our testing is relatively low is that the measures that we're taking that reduce the rate of COVID-19 actually reduce other respiratory illnesses as well, and because we generally test people with symptoms of respiratory illness, if we have less respiratory illness in the community, fewer people will be will be presenting testing,” she said.

When asked whether the province had any plans or benchmarks at which it would implement stricter restrictions, particularly in light of Ontario communities extending lockdowns as they hunt for variants, Gustafson suggested that wasn’t necessary.

“The mode of transmission, how long you're infectious, the fact it’s spread through respiratory droplets – those have not changed (with the variants),” she said. “Which means, really, it's really not a question of doing something different. It just makes us sure that we absolutely have to do our very best to follow those measures and to really do excellent case and contact management, which means that all contacts who were asked to self-isolate, actually need to self-isolate, need to adhere to those recommendations given by public health, because there's less room for error.”