VANCOUVER -- B.C. marked a grim anniversary on Wednesday: five years since the overdose crisis was declared a public health emergency. In that time, 7,072 people have died.

While the province is moving forward with plans aimed at decriminalization, there are calls to take more action now to save lives.

In Vancouver, members of the group Moms Stop the Harm gathered to join a local rally, many holding photos of loved ones lost to overdoses. Annie Storey came with a picture of her son, Alex, who died in January at the age of 28.

“It’s impacted so many families, and so many people,” she said. “The awareness still isn’t where it needs to be.”

Provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry called the five-year toll of the crisis “staggering and devastating."

“This pandemic has only made things worse, and we know that,” she said. Last year saw the highest loss of life so far, at 1,724. “We are not giving up, as much as it is too painfully slow.”

Deb Bailey with Moms Stop the Harm lost her 21 year-old daughter, Ola, in 2015.

“It’s an emergency, but where is their emergency response?” she said, and added she always considers whether the changes made up to this point could have saved her daughter. “I think they’d go a ways towards that, but nothing is going to keep people alive unless we can provide them an alternative to the toxic drugs that are out on the street...nobody can go for treatment or anything else if they’re dead.”

Bailey said her group is advocating for a safe supply, and wanted to show support for a “compassion club” model set up by the Drug User Liberation Front, which supplied drugs that had been tested.

The group had a tent set up at the site of a rally at Hastings and Dunlevy. Organizer Eris Nyx said people have to be over 18 and already using illicit drugs to participate.

“This is a way to prevent people from getting drugs with an unpredictable content and overdosing and dying,” she said. “It is a model that could be expanded immediately by drug users all over the country if the government was willing not to arrest people.”

B.C.’s Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson said the province plans to follow through with a previously stated intention to request a Health Canada exemption to decriminalize personal drug possession.

“We feel the urgency of the situation. We’re working as fast as we can,” Malcolmson said.

However, it’s still not clear when the request will be made. In a press release, the province said issues to consider include defining simple possession and determining allowable drug amounts. Consultations are being planned with various stakeholders, including Indigenous partners, law enforcement, and public health.

“We‘ll have more news on timeline when it’s nailed down with Health Canada,” the minister added.

The province is also earmarking $45 million over three years for overdose prevention measures in the upcoming budget, and added the promised funding “will extend and enhance the funding announced in August 2020."

Last year’s announcement was for $10.5 million, and was also intended to boost overdose prevention, including “expanding access to safe prescription alternatives...add new outreach teams...open 17 new supervised consumption services and 12 new inhalation services."

BC’s Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe said her office will undertake another death panel review of the crisis, following one conducted in 2018.

“This will include a review of actions taken in response to previous recommendations, and the potential for innovation, such as safe supply, to reduce or remove the dependence of so many on the perilous illicit drug market,” she said.

Lapointe said death due to illicit drug toxicity is now the fourth highest cause of death in the province, and the average age of those dying is 43.

“Males continue to account for 80 per cent of the deaths, and using alone, or only in the presence of others also using, continues to pose a significant risk,” Lapointe said.

The toxicity of the drugs has also been increasing, with higher fentanyl concentrations being found. Recently, a depressant drug called etizolam has also been detected, which Lapointe called “extremely addictive."

The province said Indigenous communities have been especially hard hit, with the First Nations Health Authority reporting 89 deaths between January and May of 2020 – a 93 per cent increase compared to the previous year.

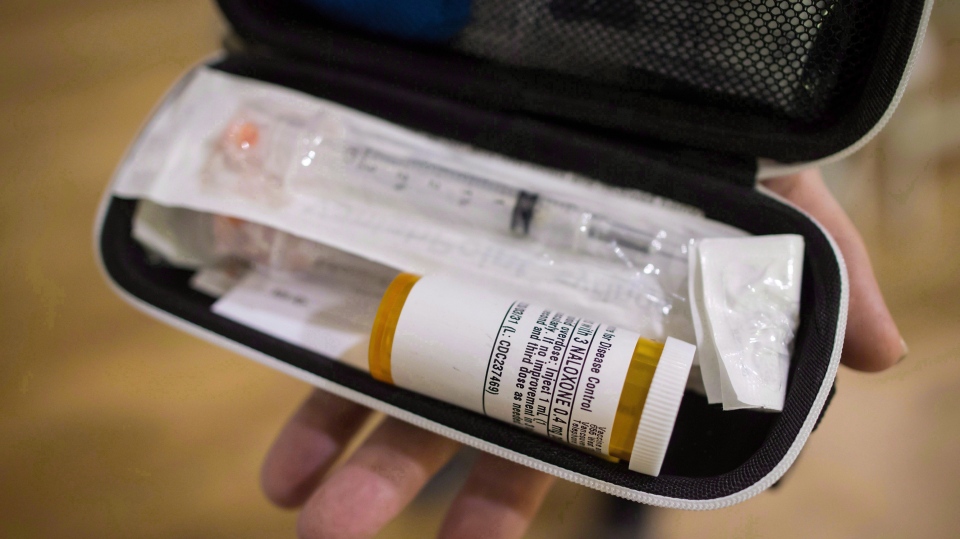

“While we know that naloxone is generally effective at reversing opioid overdoses, it is often not effective against these concoctions of opioids, sedatives, and stimulants,” Lapointe said. “We cannot continue with the current state. We must resolve to do much better.”