The vulnerability of public transit systems to terrorist attacks during the 2010 Winter Games doesn't appear to be a major concern for security planners, despite the heavy reliance to move people and athletes on public buses and trains.

Recent bombings on the London and Madrid transit systems are invoked as justifications for the Games' $900-million security budget.

Yet despite an attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team earlier this month in Pakistan, there are still no immediate plans to screen thousands of people using Vancouver's Skytrain system.

The trains runs alongside two major Games venues and almost underneath the main press centre.

"The threat that we've seen around the world, we fortunately haven't seen that here with respect to incidents that have occurred in the United States, and London and in Spain," said Supt. Kevin DeBruyckere, an operations officer with the RCMP-led security unit overseeing the Games.

"That's what we want to prevent, we don't want that to happen here."

A Vancouver transit official said they recognized after the attacks in London and Madrid that their system could be vulnerable and have since been working to strengthen security.

But Sgt. Jason White wouldn't divulge plans for the Games, other than to say the presence of transit police would be felt.

"The existing threat level, as we understand it, doesn't call for, we've not planned for mag-and-bag," he said, referring to magnetic wand and bag searches.

If the threat changes, so too will the plan for transit, both men said.

But it's those softer targets such as transit that are becoming favoured targets for terrorists, security experts say.

"The desire to attack the Olympics has always been there but most major terrorist organizations have always steered clear because the logistics would be almost impossible, there would be no real guarantee of success," said John Thompson, a security analyst who runs the Mackenzie Institute.

"But attacking a sports team in transit, certainly, that might well be the case."

That was exactly the case in the recent attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team while in Pakistan for a tournament. Their convoy was ambushed, six athletes were injured and six policeman were killed, along with a driver.

"What the bad guys saw was a gap, they saw a gap in security," said Ray Mey, a former FBI counterterrorism officer who worked on Games security from 1996 to 2006, and now consults for private security firm Garda.

"They start at the highest level and if they see that gap and vulnerability there, which they were able to do (in Pakistan), then that's their No. 1 target."

The attacks in Pakistan also proved that athletes remain as enticing a target to terrorists as they were at the 1972 Olympics in Munich.

There, eight Palestinians broke into the athletes village, killed two Israeli athletes immediately and kidnapped nine others. All nine were eventually killed in a botched rescue attempt, along with five of the attackers and one policeman.

"These types of high-value targets are symbolic representations of a country," said Mey.

"If people show they can go after and exploit them and hurt them, they are hurting the whole country."

Games security budgets have been steadily rising since 1972, despite few direct attempts on athletes since then.

At the 1976 Games in Montreal, the Front de Liberation du Quebec claimed they planted a bomb in the washroom of the Olympic stadium, though no explosives were found.

Rockets fired from the Tokyo airport during the 1988 Nagano Games and an explosion in 1996 in Atlanta were both linked to the Olympics, though the athletes themselves weren't direct targets.

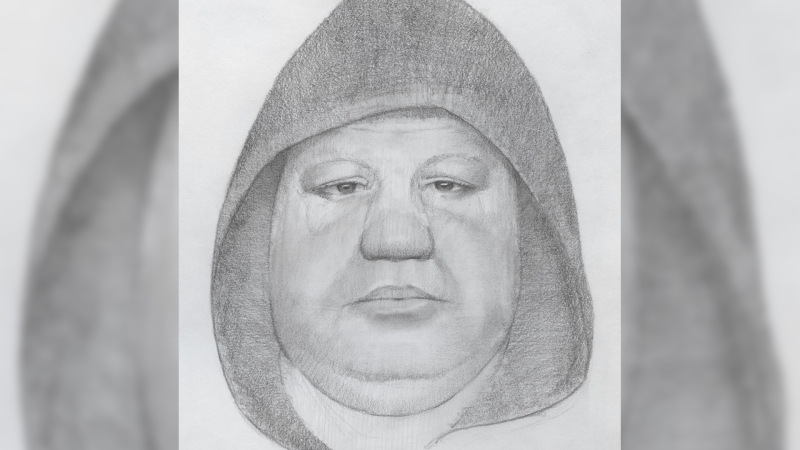

Threat assessments suggest that the risk for 2010 comes from both international terrorist cells and local activists but planners say the attack in Pakistan hasn't added a new threat potential.

Security planners say they're not concerned about an aspect of the recently-released Games transportation plan that sees athletes taking public transit to go to events other than their own.

White said he doesn't expect to see many athletes on the transit system, given they'll be busy.

Meanwhile, DeBruyckere said his team is working with the security liaisons for all of the national Olympic teams to develop the protocol for keeping athletes safe when they're outside the Olympic grounds.

While dignitaries and the public present tempting targets, it's the athletes who are the main reason for heavy security, said Mey.

For years, the highest value has been placed on both American and Israeli teams.

"(Other) teams are not afforded a lesser security standing but they are of a lesser concern because they don't have the political antipathies that the U.S. and the Israelis have," he said.

When a relative of a U.S. Olympic volleyball coach was stabbed during the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing, some other English-speaking teams made sure they wore their uniforms around town to distinguish themselves from the Americans, so as not to be considered a target.

"The difficult thing is there is no way you can completely secure an event like this," said Mey.

"All you can do is take reasonable measures to protect the public, and protect the athletes and the venues and that's a difficult job."