Rajiv Jhangiani grew accustomed to the emails he would receive from his students at the start of each semester:

“Is a previous edition OK?”

“Do I really need the textbook?”

The psychology instructor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University saw an increasing number of students attempting to go without the $150-$250 textbooks he was assigning for his courses, so he decided to stop assigning them.

“I think it’s absurd, really,” Jhangiani said. “Every two-to-three years we get new editions which are basically cosmetic in terms of the changes that they have, and students are forced to spend a lot of money.”

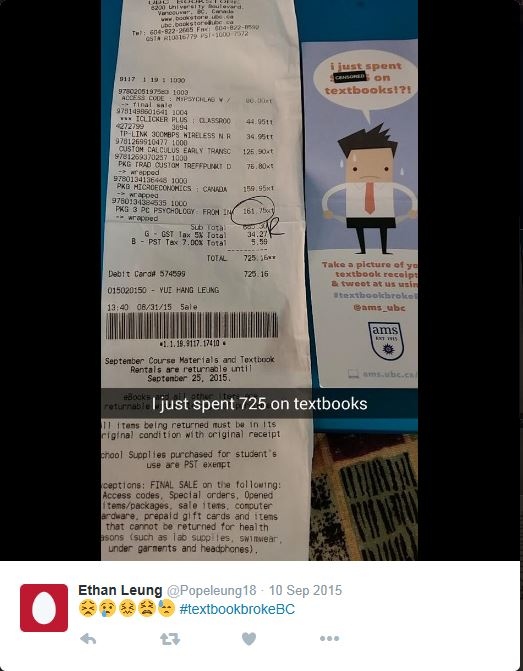

On Twitter, UBC’s Alma Mater Society has asked students to tweet photos of their receipts with the hashtag #textbookbrokeBC.

Students CTV News spoke to said they had done everything from downloading books illegally, to copying notes from friends, to just not bothering to buy the books in the first place.

“We just studied off the professor’s lecture notes,” said one student. “He said some stuff was in the textbook, but we just didn’t buy it because it was too much.”

Jhangiani now uses open textbooks - course materials that are available for free online under a creative commons license, which means they can be adapted, revised, contextualized, and redistributed without fear of violating copyright laws.

In 2012, the government of British Columbia announced that it would provide funding to support the creation of open textbooks for the 40 most-popular undergraduate courses offered in the province.

A later wave of funding added another 20 books for trades and technology subjects, but because of the continuous revision open textbooks allow, there are 140 resources in the BC Open Textbook Collection, not to mention the thousands of other open source course materials that have been created for other jurisdictions over the years.

Jhangiani said students have saved “something like $174 million” worldwide because their instructors have switched to open textbooks. In B.C. alone, students have saved more than $1 million, he said.

This is important, Jhangiani said, because recent research he helped conduct found that roughly 60 per cent of B.C. students have avoided purchasing at least one of their textbooks because of cost.

“Textbooks have gone up by about 1,000 per cent since 1977, and even four times the base of inflation in the last 10 years,” Jhangiani said.

“Students are expected to spend anywhere from $1200 to $1500 a year on textbooks. Now, of course, they’re not doing that, because as cost of living and tuition has gone up, textbooks are one of the things that tend to be discarded when students are choosing between groceries and course materials.”

Jhangiani’s research surveyed more than 400 students from 12 B.C. universities. It found that roughly 40 per cent had downloaded textbooks illegally, 35 per cent had avoided signing up for a class because they knew the textbooks would be too expensive, and 23 per cent have dropped a course because of the cost of the instructional materials.

Open textbooks are a viable solution to this problem, he said, because other studies have shown that there is little difference in educational outcomes between students taking courses that assign traditional textbooks and those taking the same courses using open textbooks.

“Really, for me, it’s a social justice issue, because if students can’t afford the required course materials, who are we saying higher education is reserved for?” Jhangiani said.

“There’s a few things that we can control as faculty. We can’t control the cost of living or tuition, but when it comes to course materials, that’s under our control, and this is where we have more of an impact than we realize.”