VANCOUVER -- On the morning of Dec. 1, 2018, Meng Wanzhou, the chief financial officer of Chinese telecom giant Huawei and the daughter of its founder, touched down in Vancouver.

Meng planned to visit one of her two Vancouver homes to drop off some boxes, then catch an evening flight to Mexico City.

Eventually, she planned to continue on a trip that would take her to Costa Rica and the G20 in Argentina, with a stop in Paris on the way home.

Instead, as she stood up from her business class seat onboard the Cathay Pacific 777, and stepped into the glass jetway, she was approached by two Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officers.

One of them checked her Hong Kong passport to confirm her identity, then asked for her phones: one white iPhone 7 Plus, and one red Huawei 20 RS Porsche Design, which Meng handed over to him.

The other officer placed the phones in mylar bags provided by the RCMP, who had made the request to the CBSA on behalf of the FBI, then put them in his cargo pants pocket.

Three RCMP officers stood watching out of view nearby.

Border officers examine Meng for nearly three hours

The CBSA officers escorted Meng to the main international arrivals hall, where a kiosk spit out a receipt directing the executive to what's known as "secondary inspection."

The officers, along with a supervisor, searched Meng's luggage, and questioned her on-and-off for two hours and 36 minutes, as part of what they called a routine admissibility exam.

Those officers have since testified they had concerns related to national security and serious criminality.

During that exam, Mounties waited in a supervisors' office that was within view of Meng, they have testified, but out of earshot.

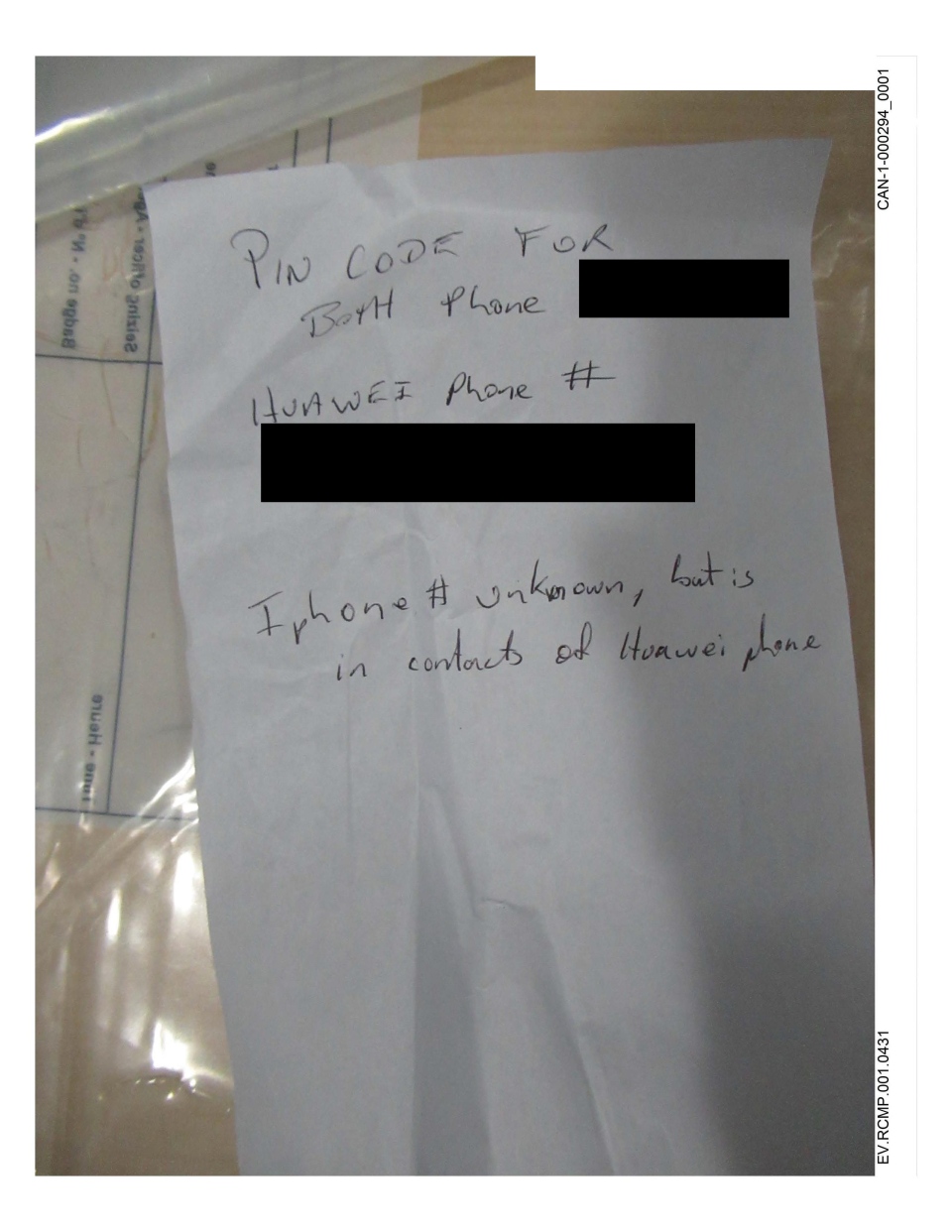

In the final moments of the exam, a CBSA officer asked Meng for the passcodes to her phones, which she provided, and which he wrote down both in his notebook and on a loose sheet of paper.

Passcodes to Meng Wanzhou’s phones obtained by CBSA and given in error to RCMP (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

RCMP arrest Meng and seize her electronics

Three hours after she landed, Meng was arrested by the RCMP.

Mounties informed her she was facing bank and wire fraud charges in the U.S. and that there was a request for her extradition.

The charges dealt with allegations surrounding Meng's role in Huawei's business dealings in Iran, and how Meng's alleged actions put a bank at risk of violating U.S. sanctions.

Meng and Huawei have repeatedly denied any wrong doing.

An RCMP constable, with a Mandarin-speaking constable standing by, read Meng her Charter rights and asked if she wanted to contact a lawyer.

RCMP also took custody of her electronic devices, including the loose sheet of paper with the passcodes to her phones.

Meng's luggage, house keys, and the code to her home alarm system were given to a friend who had been waiting to meet her.

Under virtual house arrest as two Canadians are accused of spying in China

Nearly two years after that day, Meng hasn't left Canada.

She remains under virtual house arrest, on $10 million bail and conditions that require her to wear an ankle-monitoring bracelet, abide by a curfew, and to pay for her own private security team to prevent her from leaving the country.

Meanwhile, two Canadians, former diplomat Michael Kovrig and entrepreneur Michael Spavor, who were arrested in China just days after Meng's arrest, have been charged with spying by Beijing.

The "two Michaels," as they've come to be known, have spent nearly two years in jail with little-to-no access to consular officials.

Meng Wanzhou, right, leaves home for a court appearance in downtown Vancouver on Wednesday, May 8, 2019.

Defence team: Canadian authorities delayed Meng's arrest to extract evidence to help the FBI

Meng's lawyers allege that the RCMP and CBSA co-ordinated and conspired with U.S. authorities to delay her arrest in order to extract evidence that could help the U.S. prove its case.

Her defence team alleges the actions taken by the RCMP and CBSA, both of whom Meng is also suing, violated her rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

They argue that the violations amount to an "abuse of process" of Canadian justice so grave, that the extradition case against her, currently being heard in B.C. Supreme Court, should be halted.

RCMP, CBSA, and the individual officers and supervisors involved in the case, with a few exceptions, have repeatedly denied any and all wrong doing.

Mounties and border officers reveal their version of events for the first time

For the very first time, the RCMP and CBSA officers who came into contact with Meng Wanzhou that day, along with their supervisors, have told their version of how the encounter unfolded.

Over the past few weeks, they've answered questions from both the attorney general and Meng's defence lawyers about the circumstances surrounding her arrival, her questioning, her arrest, and her electronic devices. Meng's defence team plans to use any gaps, doubts, and discrepancies from the witness testimony as they make their abuse of process arguments before Associate Chief Justice Heather Holmes in early 2021. They also plan to make arguments that Meng is a political pawn in a trade war between Beijing and Washington, and that the U.S. cherry-picked evidence, while excluding potentially exculpatory facts, in order to mislead Canadian courts.

Depending on her findings surrounding Meng's abuse of process claims, Justice Holmes may eventually have to decide if there is also sufficient evidence in the case to extradite Meng to the U.S. Experts have said appeals, if the judge rules against Meng, could take years.

What follows is some of the more revealing testimony from key witnesses in October and November 2020, and how it may impact a case that's put both Vancouver and Canada at the centre of a political and economic battle between two global superpowers.

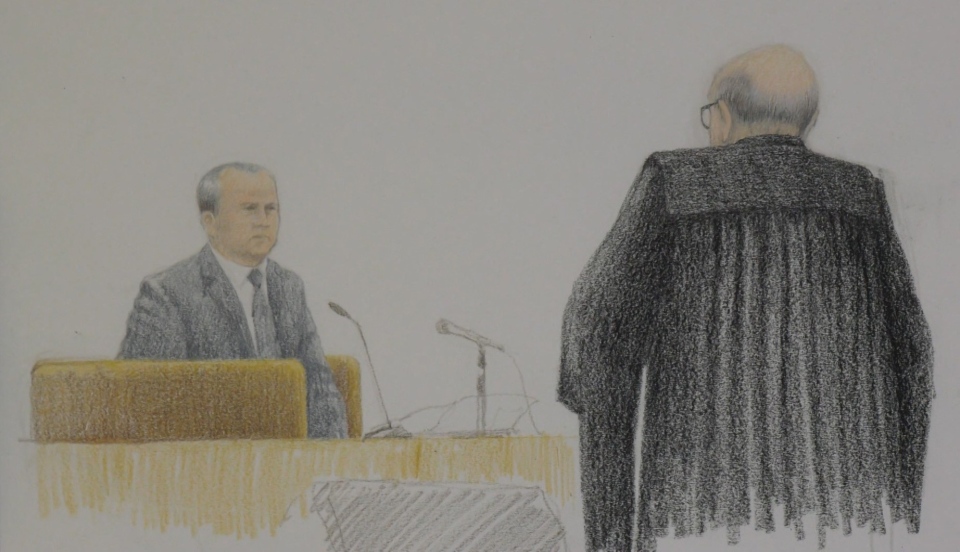

RCMP Const. Winston Yep, the officer who arrested Meng

RCMP Const. Winston Yep testifies in October 2020 in B.C. Supreme Court (Sketch by Jane Wolsak)

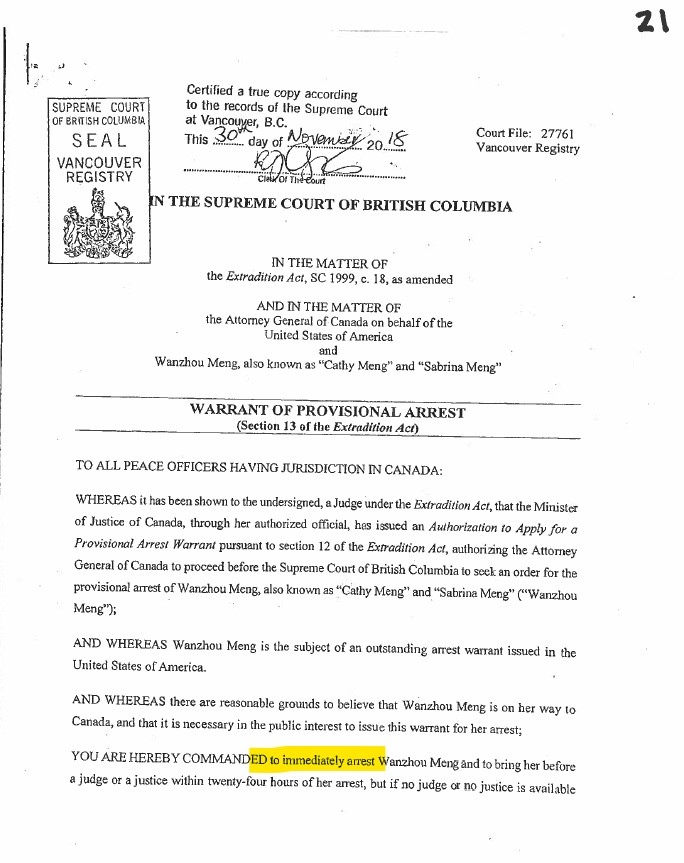

Const. Yep, who worked for an RCMP unit at B.C. headquarters that handles requests from outside jurisdictions, testified he first learned about the U.S. extradition request the afternoon before Meng arrived. He swore an affidavit in order to obtain a Provisional Arrest Warrant, which said Meng appeared to have no ties to Canada. Yep later learned Meng had two homes in Vancouver, but admitted in his testimony he never made any effort to correct the affidavit.

The evening of Nov. 30, Yep testified, he and a colleague, Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal met with CBSA personnel at YVR. Yep testified that the purpose of the meeting was to confirm if Meng was on the flight from Hong Kong, not to discuss the plan for the arrest. That evening, he testified, he became aware an RCMP higher-up had suggested Yep arrest Meng onboard the plane. "It was just a suggestion," Yep testified.

On the morning of Dec. 1, Yep, Dhaliwal and other Mounties joined members of the CBSA at YVR in a meeting in a supervisors' office. Yep testified he had "safety concerns" about arresting Meng on the plane. Defence lawyer Richard Peck pushed back and suggested Yep was lying: "My view is that is not an honest answer. Safety was never an issue," Peck alleged. Yep disputed Peck's allegation, in part, by responding that safety, when it comes to arrests, is always an issue.

During the morning meeting, Yep testified, it was decided CBSA would meet Meng at the plane. Two CBSA officers would conduct an admissibility exam for immigration and customs purposes in the secondary inspection area, before handing Meng over to the RCMP who would arrest her. Yep testified that Mounties asked CBSA officers to take Meng's phones and place them in mylar bags so they couldn't be remotely wiped, at the request of the FBI.

With respect to the CBSA exam, Yep testified the delay was "not intentional" and that three hours was "not unreasonable." He testified that Mounties had no contact with Meng and while they waited in a CBSA supervisor's office nearby, they had "no influence" with the CBSA process.

Yep also said he never asked CBSA officers, nor could he recall any fellow RCMP member asking the CBSA, to obtain any information from Meng during their exam.

The provisional arrest warrant for Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou which calls for an immediate arrest (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

RCMP Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal, the 'exhibits officer' in charge of Meng's electronic devices

RCMP Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal testifies in November 2020 in B.C. Supreme Court (Sketch by Felicity Don)

Const. Dhaliwal testified while his colleague, Const. Yep, was the arresting officer, he took on more of a communications role, as well as responsibility for Meng's electronic devices.

He attended the Nov. 30 meeting with Yep at YVR, which he called a "brainstorming session" and testified he recalled a CBSA supervisor suggesting that the RCMP could arrest Meng Wanzhou in the jetway.

Dhaliwal testified that at the Dec. 1 morning meeting, he could not recall who decided CBSA would take the lead and complete its exam before RCMP could arrest Meng. He indicated that he did not read the arrest warrant until days later. Dhaliwal also testified that he, Yep, and their direct supervisor, Sgt. Janice Vander Graaf were within view of the gate when two CBSA officers identified Meng, asked her for her phones, and placed them in the bags, he testified.

During the CBSA exam, Dhaliwal testified he was charged with making regular updates to his unit as well as to a Canada Department of Justice lawyer.

Dhaliwal testified that he did not direct the CBSA in its exam or pose any suggestions about what questions its officers should ask.

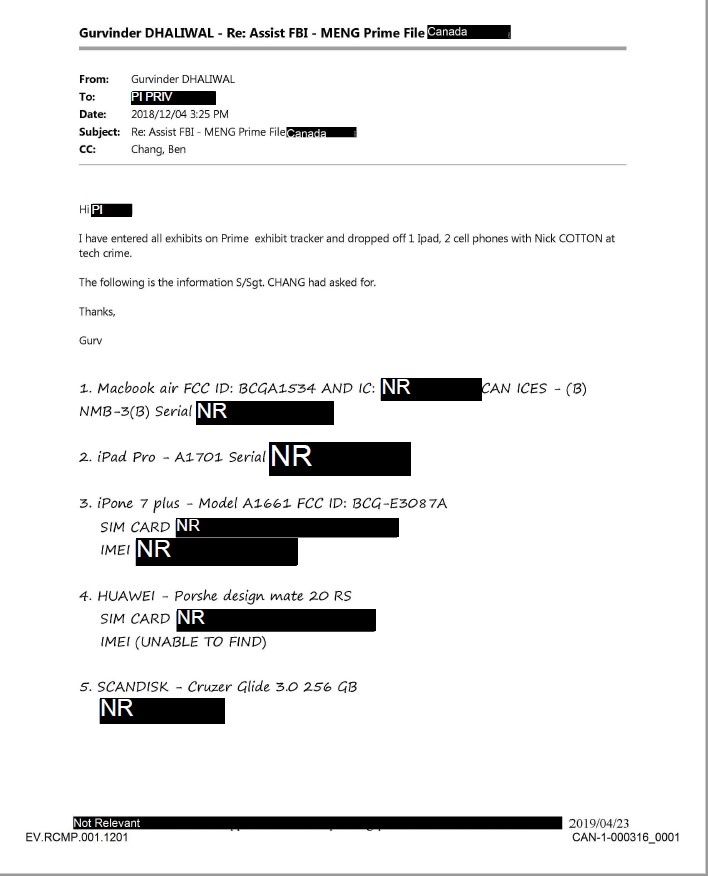

After Yep arrested Meng, Dhaliwal took custody of Meng's two phones, laptop, tablet, and a USB flash drive. He testified that CBSA Officer Scott Kirkland also handed him a loose sheet of paper with the passcodes for Meng's phones. Dhaliwal testified he "didn't even think about it" and just put the paper with the phones. He said at no point did he or any RCMP member ask CBSA to obtain Meng's passcodes.

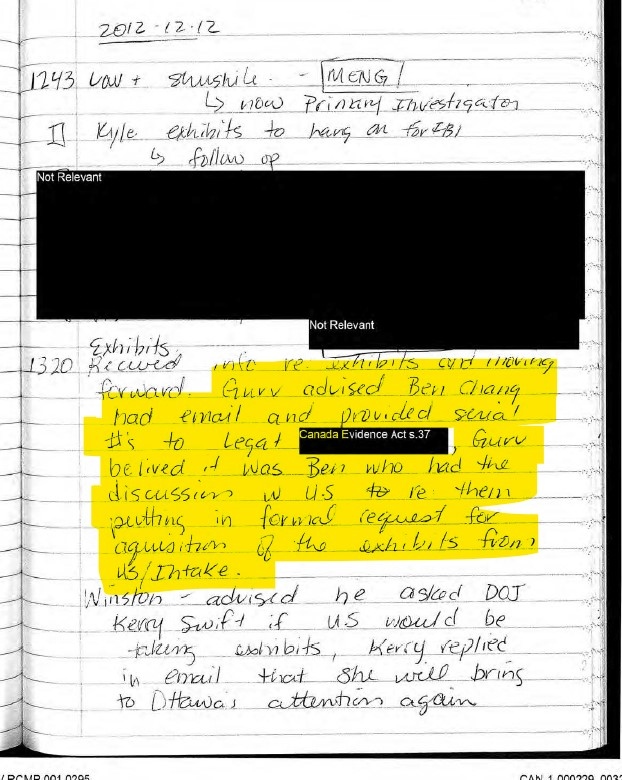

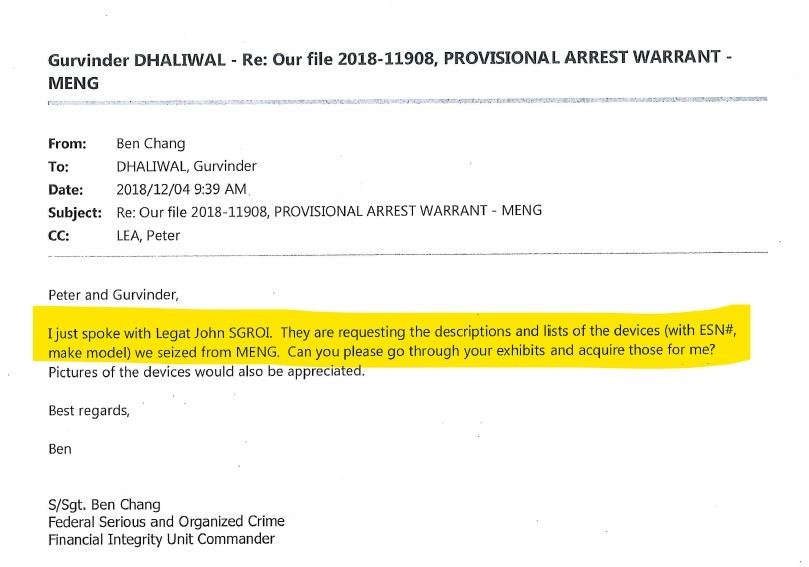

Dhaliwal also testified about his dealings with RCMP Staff Sgt. Ben Chang, who led a team within the B.C. RCMP's Financial Integrity Unit. Email records from three days after Meng's arrest show Chang had been in touch with an FBI legal attaché. Those emails show Chang requested Dhaliwal to document and provide him with identifying information for Meng's devices, including serial numbers and photos.

According to her notes, Sgt. Janice Vander Graaf, Dhaliwal's direct supervisor, wrote that Dhaliwal later told her that Chang shared those numbers with the FBI. Dhaliwal testified he did not recall telling Vander Graaf what she wrote in her notes, and did not believe any RCMP member, including Chang, illegally provided evidence to U.S. law enforcement.

Dec. 2018 email from RCMP’s Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal to RCMP’s Staff Sgt. Ben Chang with a list of identifying information for Meng Wanzhou’s electronic devices (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

RCMP Sgt. Janice Vander Graaf, constables Yep and Dhaliwal's direct supervisor who leads B.C. RCMP's Federal Serious and Organized Crime - Intake Unit and Foreign and Domestic Liason Unit

RCMP Sgt. Janice Vander Graaf testifies in November 2020 in B.C. Supreme Court (Sketch by Felicity Don)

Sgt. Vander Graaf, who testified she started as a patrol officer in Surrey and has two decades of policing experience, is one of the senior Mounties ultimately responsible for Meng's arrest. She testified she first learned about the extradition request the afternoon of Nov. 30, and was in touch with constables Yep & Dhaliwal throughout the afternoon and evening.

Vander Graaf testified that during a phone call with her supervisor, Acting Insp. Peter Lea, Lea made a "strong suggestion" that RCMP arrest Meng onboard the plane. Vander Graaf conveyed that message to Dhaliwal Friday night, but also testified she told him it would be fine to alter that plan if there was a reason.

On Dec. 1, Vander Graaf was on a scheduled day off. But that morning, she testified, she received a call from Sgt. Ross Lundie, a Richmond Mountie stationed at YVR, who told her he wanted another senior officer onsite.

Vander Graaf's notes show she arrived late to the meeting with CBSA. By the time she joined, she testified, the decision for CBSA to conduct its admissibility exam first, had already been made. Defence lawyer Scott Fenton asked if she expressed concerns, or called her boss to make him aware of the change in plan. Vander Graaf testified she did not object and did not think she called her supervisor. She also told Fenton that she had safety concerns about arresting Meng on the plane. When Fenton accused her of "making this up into a much bigger thing (than it was)," Vander Graaf denied the accusation, and testified her concerns surrounding safety were genuine.

In revealing testimony that verged on combative, Vander Graaf also admitted she didn't read the arrest warrant, which called for Meng's "immediate arrest," until 15 or 20 minutes before the flight landed from Hong Kong. Fenton pointedly suggested that because she hadn't read the warrant, Vander Graaf never took what he called a "commandment for immediate arrest" into consideration.

Vander Graaf also testified she did not know how long CBSA's exam of Meng would take because it was "their process." When Fenton asked her if, hypothetically, the CBSA exam had taken two days, if the RCMP arrest would still be considered "immediate," she replied: "That could be, yes."

Defence also established that there had been some sort of "chit-chat" between CBSA and RCMP during the exam because Vander Graaf had written in her notes at the time Meng was carrying household goods, and the only place that detail could have come from, defence pointed out, was the CBSA.

When it came to Meng's phones and the paper with her passcodes, Vander Graaf testified she told Dhaliwal to log them, because "he couldn't unseize something that he'd already seized," and that giving them back to Meng would be "less transparent."

Regarding her notes that Dhaliwal told her on Dec, 12 that RCMP Staff Sgt. Ben Chang had illegally provided identifying information about Meng's devices to the FBI, Vander Graaf stuck by her notes, then testified her concerns were later assuaged after she reviewed emails between Dhaliwal and Chang. Vander Graaf said she didn't take any further action because the emails, she said, provided more context and did not specifically indicate the evidence had been illegally shared. She also testified that she would have "left it alone regardless" because it was Chang's responsibility.

In a fiery exchange, Fenton accused Vander Graaf of lying on the stand, and "developing a memory," because he said her testimony about some of those emails was inconsistent with an affidavit she filed in 2019, where she wrote she had no independent recollection about those same emails.

Meng's lawyer accused her of "tailoring her evidence" to protect the RCMP and to cover up alleged information sharing with the FBI.

"That is absolutely not true," Vander Graaf said.

A page from RCMP Sgt. Vander Graaf’s notebook which indicates another RCMP member shared information about Meng’s phones with the FBI (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

RCMP Sgt. Ross Lundie, one of the supervisors for the Richmond RCMP detachment office based at YVR

A court sketch from Jane Wolsak shows RCMP Sgt. Ross Lundie.

Sgt. Lundie appears to have been one of the first Mounties aware that something unusual was about to transpire.

As a supervisor for YVR office of the Richmond RCMP detachment, he testified he got a call from a colleague in Ottawa a week before Meng’s arrival. Lundie said the colleague asked questions about the “flow” of arriving international travelers at YVR, and whether a traveller could exit the airport without encountering a CBSA officer.

Lundie, who joined the RCMP in the late 1990s, testified he did not learn the name of the arriving traveler until the evening of Nov. 30, when he was asked to provide assistance to the RCMP’s Foreign Domestic Liaison Unit, as well as provide a Mandarin-speaking constable the next day.

Lundie testified that he talked to constables Dhaliwal and Yep that evening on the phone, who raised the idea of arresting Meng on the plane. He testified that he “had concerns with that right off the bat.” He had years of experience working alongside CBSA officers, Lundie said, and “it’s not something that we do,” he testified, unless there is an “immediate public safety risk.”

That evening, Lundie testified, he exchanged emails with higher-ups about Meng, telling some of them to “Google the name,” realizing she was “extremely high profile.”

On Dec. 1, Lundie woke up to emails from FBI legal attaché Sherri Onks, who he had previously met, and who asked him to keep her posted on Meng’s arrest. Lundie testified the request seemed “reasonable” but also that he was not the lead on the case, instead indicating the RCMP’s Foreign Domestic Liaison Unit under Sgt. Janice Vander Graaf.

Lundie attended the morning meeting at YVR with constables Yep and Dhaliwal and members of the CBSA. He testified that he suggested that CBSA conduct their examination of Meng first, and RCMP would arrest her after. Lundie said CBSA left the room to discuss, then returned and agreed, saying “that made sense.”

He also testified that he told CBSA that RCMP would not direct them in their exam, and said he was fully aware the two processes needed to be kept separate and any information sharing should only happen through formal channels.

Lundie said he didn't recall if "sanctions" or "Iran" came up at the morning meeting.

Under cross-examination, Lundie told defence lawyer Richard Peck that while the RCMP requested CBSA to bag Meng's cellphones, at the request of the FBI, he viewed that as a “reasonable” request because it was "just to secure them."

Lundie also told Peck that that during Meng's CBSA exam, he recalled hearing a conversation in the doorway of the CBSA superintendent's office, where he and Mounties were waiting, between either Const. Yep or Const. Dhaliwal and a CBSA officer that mentioned "passwords" or "passcodes."

He testified that he didn't speak up because he didn't understand the relevance, and didn't realize CBSA had obtained Meng's passcodes

"I had no idea why there would be passwords to phones obtained by anybody," Lundie said, before admitting in retrospect, as a senior officer concerned about blurred lines between CBSA and RCMP roles, he should have spoken up.

While Lundie testified he was tasked by RCMP higher-ups with acting as the contact at YVR for the FBI legal attaché the day of Meng's arrest, he testified he did not pass any information to the FBI "that he shouldn't have."

He also told Peck that given his experience and position, he found being designated the FBI point-of-contact onsite put him in a "very uncomfortable position."

A picture of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou’s Hong Kong passport (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

RCMP Staff Sgt. Ben Chang, the now-retired officer who led a team within the B.C. RCMP's Financial Integrity Unit and liased with an FBI legal attaché about Meng's electronic devices

An internal email from Dec. 2018 from RCMP Staff Sgt. Ben Chang to RCMP Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal requesting he compile identifying information about Meng Wanzhou’s electronic devices (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

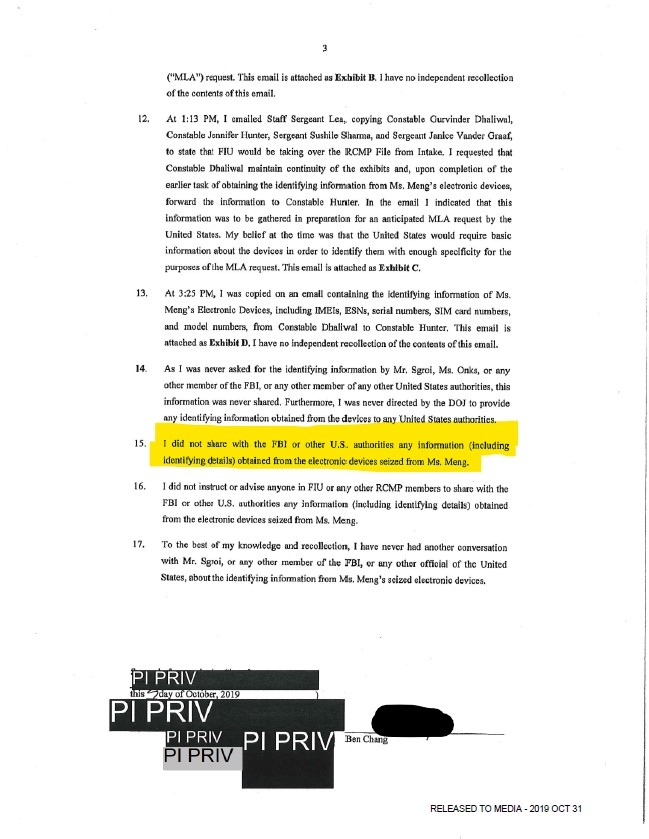

Retired Staff Sgt. Ben Chang is the only witness in the Meng case to date who has declined to testify.

Defence accuses Chang of illegally providing identifying information about Meng's electronic devices to the FBI, details they allege may have allowed U.S. investigators to access Meng's phone records and text messages.

In an affidavit, Chang writes he was never specifically asked for the unique identifying numbers to Meng's devices from anyone at the FBI. Moreover, he writes, the information was never shared.

His affidavit appears to be at least partially contradicted by an email from Chang to Dhaliwal that indicated the FBI legal attaché had requested "descriptions and lists of the devices" including the serial numbers.

Chang maintains in his affidavit that he asked Dhaliwal to gather only "basic information" about Meng's devices, along with photos, because he believed U.S. authorities would need it to make a formal request for the devices through a process known as the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT).

According to the Globe & Mail newspaper, Chang now works as a senior security executive at a hotel and casino in Macau, which, like Hong Kong, is a special administrative region of China.

Lawyers for Canada's Attorney General, according to documents filed with B.C. Supreme Court, have previously raised concerns around Chang related to "witness safety."

The reference, first reported by the South China Morning Post, deals with a concern related to releasing notes from a 2019 phone call between Chang and a Department of Justice official.

It's unclear if "witness safety" has any bearing on Chang's decision to not testify.

When CTV News reached Chang's personal lawyer, Joe Saulnier, of Vancouver-based Martland & Saulnier, Saulnier said Chang had no comment.

Meng's defence lawyers said Chang's refusal to testify may have "any number of consequences" and plan to incorporate it into their abuse of process arguments.

Part of an affidavit sworn by RCMP Staff Sgt. Ben Chang denying he passed details about Meng’s phones to the FBI (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

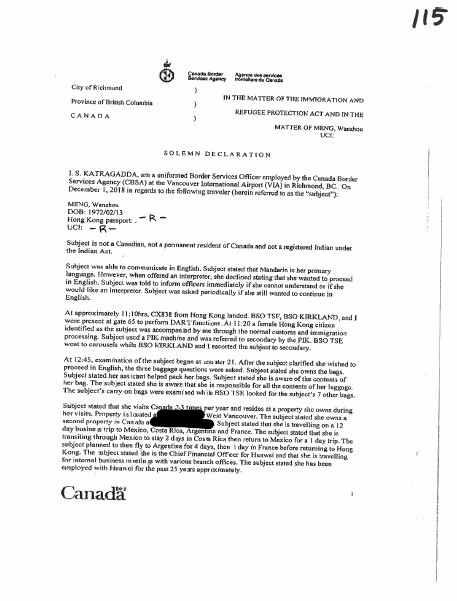

CBSA Officer Sowmith Katragadda, the border services officer who led Meng's admissibility exam for nearly 3 hours

An image from surveillance video shows Canada Border Services Agency Officers Sowmith Katragadda and Scott Kirkland examining Meng Wanzhou at YVR on Dec. 1, 2018 (Source: CBSA)

Officer Katragadda was the least experienced member of the CBSA who dealt with Meng the day of her arrest, but also the officer who had the greatest amount of interaction with her.

Katragadda, who joined the CBSA in 2015, testified he first learned about Meng at the Dec. 1 morning meeting at YVR with RCMP, where he said Mounties provided the arrest warrant.

He also testified that, while he was not familiar with the name "Meng Wanzhou," he had been previously aware that Huawei was suspect of assisting the Chinese government with spying.

Katragadda testified he had admissibility concerns related to both serious criminality and national security.

He said he did additional "open source" searching before Meng landed, which he said made him aware of the serious, high-profile nature of the matter, and that he could later be going to court.

At the morning meeting with RCMP, Katragadda testified, he suggested CBSA conduct its exam of Meng first, before handing her off to the RCMP, but testified he couldn't recall who made the final decision.

He testified he did not think the RCMP plan to arrest Meng on the plan was "appropriate" because he did not believe Meng posed an "immediate risk."

Katragadda described Meng as a "very pleasant person" during their first interaction at the gate, where he identified her and asked her for her phones.

He and Officer Scott Kirkland, who notes and surveillance video show, was chiefly assisting and taking notes, eventually escorted Meng to secondary inspection.

Katragadda asked Meng some basic questions about her travels, searched her luggage, and X-rayed some boxes of household goods.

Katragadda tesitified he was careful with his questions because he didn't want to be perceived to be asking Meng information on behalf of the RCMP or U.S. authorities.

After less than an hour, Katragadda said, he had received enough information to adjourn the exam to a later date, and because he was mindful the RCMP were waiting to arrest Meng.

But when he went to his supervisors' office, where he said Mounties were waiting, one of the CBSA supervisors on duty told Katragadda to hold off until they heard back from the CBSA National Security Unit.

Katragadda testified that decision was "not inappropriate" but "not what (he) had in mind."

The wait on a Saturday for two sets of additional questions from the unit, one of which dealt with countries Meng had travelled to, extended Meng's exam time to two hours and 36 minutes.

In the final minutes before RCMP arrested Meng, Katragadda testified that he radioed Kirkland from the CBSA supervisors' office to ask Kirkland to obtain the passcodes to Meng's two phones.

Katragadda testified that while he was the one who made the request, which he called "reasonable," he could not recall whose idea it was.

Less than 10 minutes later, notes and affidavits submitted by Katragadda and Kirkland show, RCMP arrested Meng.

Katragadda testified he did not realize Meng's passcodes had been given to Mounties in error until "days later" at a debrief with CBSA higher-ups.

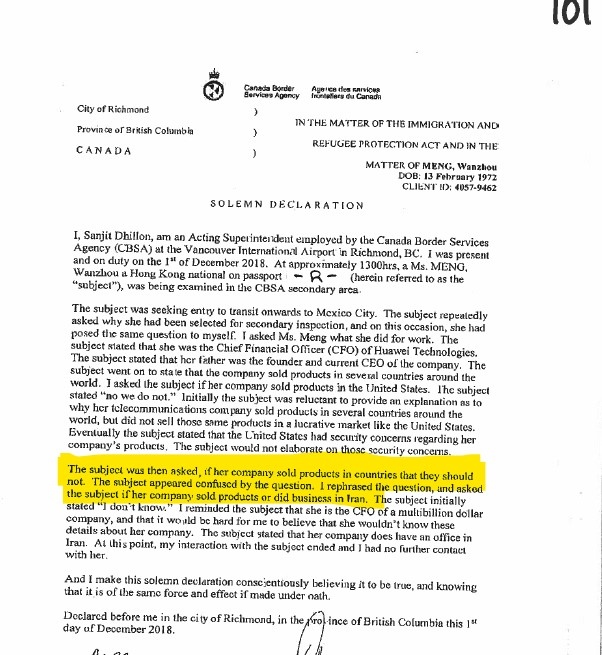

A page from CBSA Officer Sowmith Katragadda’s sworn declaration which details part of his exam of Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

CBSA Officer Scott Kirkland, the border services officer who assisted with Meng's admissibility exam and obtained the passcodes to her phones

CBSA Officer Scott Kirkland is seen in an image posted on the Canada Border Services Agency Twitter account in November 2018. (Source: Twitter/CBSA)

Officer Kirkland, who has been with the CBSA since 2008, testified that he had serious concerns in the Dec. 1 morning meeting with RCMP about possible Charter issues being raised if CBSA were to examine Meng first.

He also explained that, at a Port of Entry, there is a lower expectation of privacy which allows border officers to ask questions and conduct searches for immigration and customs purposes.

"Our examination (could) be argued as a delay in due process," Kirkland testified.

Under cross-examination, Kirkland later clarified to Meng defence lawyer Mona Duckett that while he suggested at the morning meeting that CBSA identify Meng and "step aside," he did not raise his Charter concerns.

Calling the meeting ad-hoc without "any serious in-depth conversations," he testified that RCMP did not object to CBSA going first, and did not give CBSA any direction on how to conduct its exam.

"This was a rushed discussion," Kirkland said.

Kirkland also testified that when he read the warrant and some news articles about Huawei that morning, he was shocked.

"We knew this was going to be a big deal," Kirkland said. "It was going to be a huge issue."

When Meng arrived just after 11 a.m. and handed over her phones, Kirkland was tasked with putting them in mylar bags, which he said he kept in his cargo pants' pocket.

He later testified he didn't believe the bags, which had been provided by RCMP on behalf of the FBI, were effective at blocking signal transmission, because at one point, he said, the phones were vibrating.

During the exam itself, Kirkland admitted to Duckett he intentionally did not answer Meng's repeated questions about why she was being examined in-depth, and deliberately did not mention the arrest warrant or U.S. criminal charges.

He also reminded Duckett, multiple times, that Katragadda, as lead examiner, was in charge of questioning Meng along with deciding when to end the exam.

Kirkland later conceded to Duckett she was correct when she suggested the exam did not raise "an iota of evidence to support a national security concern" when it came to Meng.

When it came to the passcodes to Meng's phones, Kirkland testified that he typically wrote passenger passcodes down both in his notebook and a loose sheet of paper, which he said he eventually returns to the traveller.

Kirkland's testimony directly contradicted Const. Dhillon's, who testified that Kirkland handed him the sheet with Meng's passcodes. Instead, Kirkland testified he left the sheet with Meng's belongings at the counter, and when he realized he had left it behind, he went back to look for it.

Kirkland testified that RCMP obtained Meng's passcodes by mistake, and he never intended, nor was he directed by anyone to provide them to Mounties.

A photo of Meng Wanzhou’s bagged phone, a red Huawei 20 RS Porsche Design, held by CBSA, then seized by RCMP after her arrest. (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

CBSA Acting Supt. Sanjit Dhillon, one of two border services supervisors on duty in secondary inspection at YVR the day of Meng's arrest. He questioned Meng about whether Huawei does business in Iran

CBSA Acting Supt. Sanjit Dhillon testifies in B.C. Supreme Court in November 2020 (Sketch by Jane Wolsak)

Supt. Dhillon testified that he "suggested" to RCMP in the Dec. 1 morning meeting, along with CBSA Supt. Bryce McRae, that Mounties would not be able to intercept and arrest Meng at the gate.

He testified that CBSA conduct its admissibility exam first, though. like his colleagues did not recall who made the final decision, saying "that's how (he'd) been trained to do it."

Dhillon said at some point after the meeting, he spent roughly five to 10 minutes on the Huawei Wikipedia page, zeroing in on the section on "controversies."

He testified he wondered "if the fraud charges (against Meng) were related to any violations of sanctions."

He also said the article, which he later conceded under cross-examination by Mona Duckett could have been edited by anyone, raised concerns about national security and spying.

Dhillon, who joined the agency in 2005, testified that he was the CBSA supervisor who relayed questions from the CBSA National Security Unit to one of the examining officers.

Near the end of Meng's exam, Dhillon said he left the supervisors' office and approached the counter, where he began questioning Meng directly.

He rejected accusations he was trying to gather evidence for the FBI, and instead stated he had national security concerns.

Based on his Wikipedia research, Dhillon testified, he asked Meng if her company "sold products in countries that they should not" and specifically if Huawei "sold products or did business in Iran."

He testified that based on Meng's "non-verbal behavior...there's more to that story I was never able to explore."

Dhillon said he made no mention to Meng of the extradition warrant or U.S. fraud charges (which dealt with Huawei's business in Iran) because, he testified, he "wanted (Meng) to speak to it."

He also admitted he did not tell Meng that RCMP were waiting to arrest her.

During her cross-examination, Duckett accused Dhillon of lying on the stand and making up his Wikipedia research as a cover story in order to ask Meng about Iran, instead alleging he learned was told about Iran by RCMP during the morning meeting.

Duckett called the research a "creation after the fact" and asked why Dhillon had singled out Iran, but not other countries mentioned on the Wikipedia page including North Korea, Venezuela, and Syria.

Dhillon categorically rejected Duckett's accusations.

He also testified that the RCMP did not "instruct (him) to do anything that day."

A page from CBSA Supt. Dhillon’s sworn declaration where he recounts asking Meng Wanzhou is Huawei does business in Iran (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

CBSA Supt. Bryce McRae, the second border service supervisor on duty in secondary inspection at YVR the day of Meng's arrest

CBSA Supt. Bryce McRae testifies in B.C. Supreme Court in November 2020 (Sketch by Jane Wolsak)

Supt. McRae testified he first became aware of the Meng case on Nov. 30, when the CBSA got a call, which emails filed in court show was from FBI legal attaché Sherri Onks.

Onks wanted a contact number for the supervisor on duty the next day, McRae later wrote in a 2019 email to Crown, because a "notable client" would be arriving.

While McRae was on duty at YVR on Dec. 1, he testified he was "not a direct player" into how events unfolded and decisions were made.

McRae said he recalled little about the morning meeting with RCMP, and testified he did not remember Officer Kirkland suggesting CBSA could quickly identify Meng, then hand her off to the RCMP to be arrested.

Defence lawyer Mona Duckett accused him of having a "poor memory."

With respect to CBSA's questioning of Meng, McRae testified he couldn't remember if he provided advice to Officer Katragadda on when to end the exam.

McRae also testified he did not discipline Officer Kirkland for his mistake in providing Meng's passcodes to the RCMP.

A photo of Meng Wanzhou’s luggage the day of her arrest at YVR (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

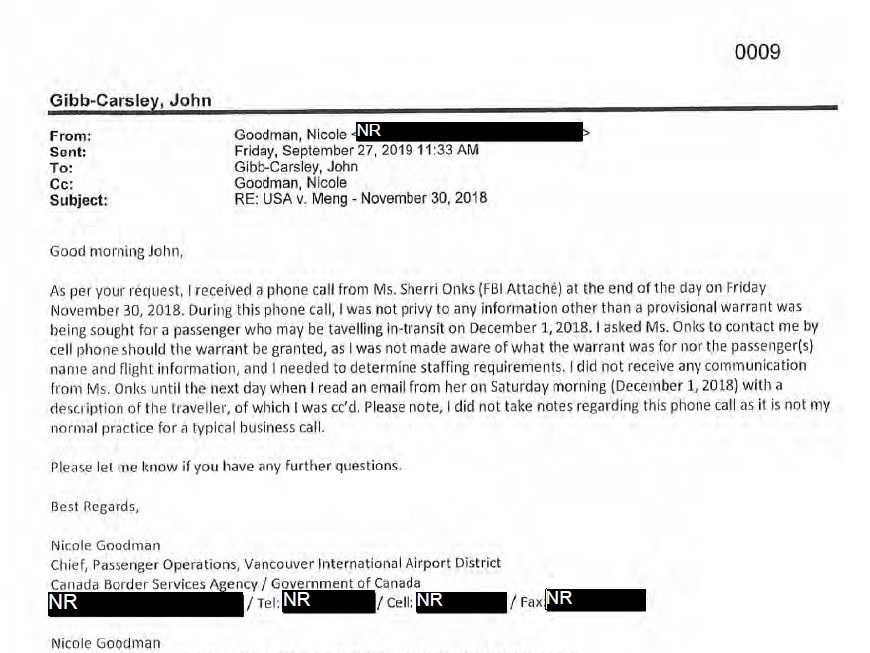

CBSA Chief Nicole Goodman, the head of passenger operations at YVR

CBSA Chief Nicole Goodman is seen outside B.C. Supreme Court on Dec. 10, 2020. (Source: The Canadian Press)

As the chief of passenger operations at Vancouver International Airport, Chief Goodman testified she oversaw a team of 250 staff, including the border officers and superintendents, working the day of Meng's questioning and arrest.

Goodman, who has more than two decades of experience with the CBSA, testified that she recalled getting a phone call from FBI legal attaché Sherri Onks on Nov. 30, 2018, alerting her a traveller would be arriving at YVR the next day, and that a provisonal arrest warrant was pending.

She testified she wasn't given the name of the traveller and later denied defence's suggestion that she "co-ordinated" with the FBI.

On the day of Meng's arrest, Goodman said she was on a scheduled day off, and kept in touch with her superintendents at YVR over the phone. She testified that ahead of Meng's arrival, she was aware the CBSA would process Meng first, and that she was aware of the request from RCMP to bag Meng's phones on behalf of the FBI, a request she called "reasonable."

Goodman also testified she helped connect her superintendents with the CBSA's national security unit during Meng's admissibility exam, which took some time, she said, because it was a weekend.

Three days after Meng's arrest, Goodman, who described herself as a bit of a stickler for information sharing, testified she debriefed the officers and superintendents involved in Meng's questioning. Of particular focus, she said, was whether any information had been improperly shared with other law enforcement agencies.

Goodman testified that she "vividly" remembered at that meeting how Scott Kirkland, one of the officers who conducted Meng's exam, "went white and seemed distressed." She said Kirkland told her about the loose piece of paper where he had written down the passcodes to Meng's phone. Kirkland, Goodman said, told her that he that didn't know where the paper had gone.

Goodman testified that she had "concerns" about what she called a serious breach and that she told Kirkland to "go figure it out." Goodman also testified she believed Kirkland's actions were "100 per cent accidental" based on his reaction and that he was a "very upstanding officer."

Under cross-examination, when defence lawyer Mona Duckett asked Goodman if she had further investigated the passcode breach, Goodman said she had not, although she testified she had "more than one conversation" with Kirkland. She also testified she did not raise the prospect of discipline with him.

Duckett later accused Goodman of waiting a month before contacting RCMP about the illegally obtained passcodes. Goodman explained that she had briefed her direct supervisor at YVR, Director John Linde, and was waiting for the green light to contact RCMP.

Goodman also testified that when she contacted Const. Gurvinder Dhaliwal in early January 2019, he told her the RCMP couldn't return the passcodes because they were evidence in court. Goodman said she told Dhaliwal that under no circumstances could the RCMP use or share Meng's passcodes.

Duckett asked Goodman if she had asked Dhaliwal how he had obtained the passwords, reading back Dhaliwal's testimony that Kirkland had "handed them to him."

"I don't remember," Goodman said.

In a rare admission, Goodman also testified that she learned someone at the CBSA had shared Meng's travel history with the FBI through unofficial channels, which she said should not have happened.

Midway through her cross-examination, while under orders not to talk to anyone about her testimony, Goodman also approached a U.S. Department of Justice official because she had concerns, she said, that her testimony may have touched on privileged information about her preparation for court with DOJ lawyers.

Justice Heather Holmes instructed the amicus curiae, an impartial lawyer who has been involved in the document disclosure process in the case, to discuss the breach with Goodman. He reported back that he had instructed Goodman to answer all questions truthfully and to the best of her ability.

Back on the stand, Goodman, who testified she had taken no notes about the passcode breach, said she wanted to create a "case summary" of CBSA's involvement with Meng.

Goodman, who described the day of Meng's questioning as "routine," but the weeks after as "extraordinary," recalled a meeting a few weeks after Meng's arrest with CBSA higher-ups, including Linde and Roslyn MacVicar, the top CBSA executive for B.C. and the Yukon.

At that meeting, Goodman said MacVicar told her creating a case summary would be "unnecessary, " because it would be her "opinion," and also subject to future disclosure requests.

Goodman tesified she couldn't recall the exact words MacVicar used, but left the meeting with the impression, she said, not to create any further records.

"That's probably the only thing that does weigh on me," she told Duckett, but offered up that there was "nothing nefarious" about it.

Goodman, who at times sounded emotional on the stand, said that one day "when this is done," she still plans to complete that summary.

A September 2019 email from CBSA Chief Nicole Goodman to Crown detailing a call Goodman received from FBI Legal Attaché Sherri Onks the day before Meng Wanzhou's arrival in Vancouver. (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

CBSA Regional Director General (RDG) Roslyn MacVicar, the top CBSA executive for the Pacific Region

CBSA Regional Director General Roslyn MacVicar with Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister Steven Blaney in 2014. (Source: Public Safety Canada)

As the top CBSA official in the region, RDG MacVicar testified she was primarily involved in the Meng matter by gathering information after-the-fact from Chief Goodman and Goodman's supervisor, Director John Linde at YVR, as well as answering questions from CBSA executives in Ottawa.

MacVicar, who retired in 2020, said she was out of town the first week of December 2018 and had "no operational knowledge" of Meng's questioning and arrest on Dec. 1.

She testified she participated in meetings with both supervisors and subordinates in the period between early December 2018 and January 2019, but said she did not take any notes or create records at those meetings.

MacVicar testified that because of widespread media coverage of the case, one of her primary concerns was that frontline CBSA officers were receiving questions that they were not authorized or equipped to answer. She tesitified that at the time she would have been cautioning her team to stick to their roles.

Under cross-examination, MacVicar recalled few details about meetings she attended both in person and virtually with CBSA higher-ups in Ottawa.

Defence lawyer Mona Duckett walked MacVicar through pages of meeting notes taken by Robin Quinn, the chief of staff to her direct boss, Jacques Cloutier, CBSA's VP of intelligence and enforcement.

Those notes included references to the CBSA superindendent (Sanjit Dhillon) who questioned Meng about Iran and the bagging of Meng's phones by a CBSA officer (Sowmith Katragadda).

When asked by Duckett if she considered it unusual for Mounties to wait in the CBSA superintendents' office at YVR while an exam was ongoing, MacVicar replied in broader terms about the relationship between her agency and the RCMP:

"It's not an everyday occurrence...but it's not unusual either because we have a collaborative relationship," she testified.

MacVicar also admitted to Duckett she did not review the statutory declarations or notes of the front-line officers or superintendents who had dealt personally with Meng.

When it came the passcodes to Meng's phones, MacVicar testified she could not recall when or how she first learned the passcodes had been illegally shared by the CBSA with the RCMP.

MacVicar agreed with Duckett the breach was a "significant incident."

Under intense cross-examination, Duckett asked MacVicar about Chief Goodman's testimony that she remembered MacVicar instructing her in a meeting to gather information but not to create notes or a case summary.

MacVicar said she couldn't recall making such a comment to Goodman.

Duckett went one step further.

"I would suggest that you did in fact direct your staff not to create any records for fear of them being disclosable," Duckett said.

"I would never say that," MacVicar responded. "I did not say that. And it's inconsistent with anything I've ever said in my life as a public servant."

Duckett pointed out that there seem to be no records within the CBSA that document Meng's passcodes being given to the RCMP or efforts to get them back.

MacVicar agreed she had not seen any.

"That's not very transparent if it's not ever documented," Duckett said.

"I don't understand how that can happen," MacVicar responded.

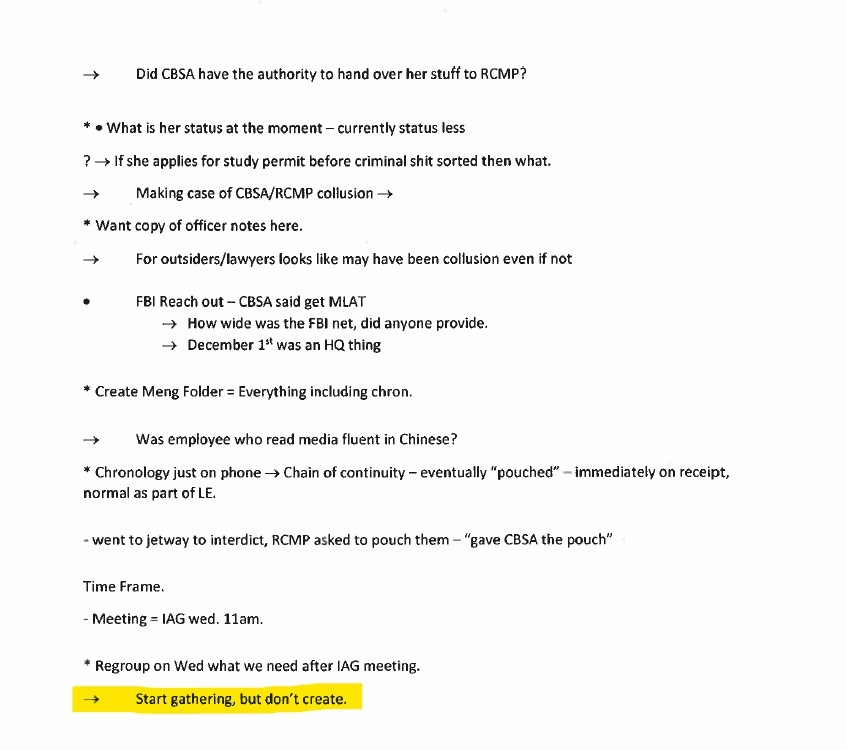

A page of typed notes from a Jan. 7, 2019, CBSA meeting on the Meng case which include the notation "Start gathering, but don't create." (Source: B.C. Supreme Court)

Meng is scheduled to return to court in early March.

Abuse of process arguments and the main extradition hearing are currently scheduled to be heard between mid-March and mid-May of 2021.