A new pilot project has been announced that will use a heat-vision camera to help Vancouver homeowners cut down on their energy bills.

Starting this month, city staff will be driving through five neighbourhoods and snapping thermal images of the exteriors of roughly 15,000 properties.

The images will help pinpoint places that heat is escaping, such as poorly insulated doorways, windows and roofs, but won't show anything that's happening inside, said Sean Pander, manager of green buildings for Vancouver.

"Privacy is well-protected," Pander said. "[The camera] can't see anything inside the house, it just sees the surfaces and the temperatures of the surfaces."

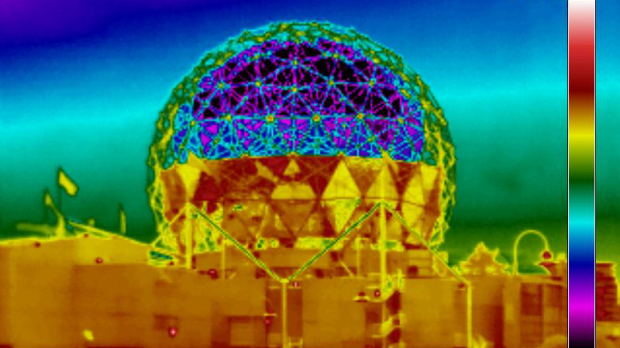

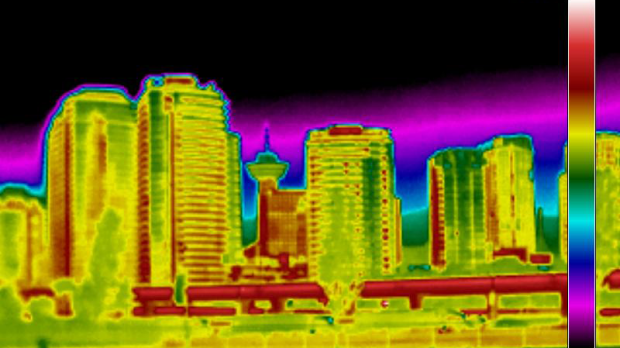

On thermal images, different temperatures show up as different colours. Cold building exteriors appear dark blue and green, while spots that are leaking heat show up white, yellow or red.

The city said staff will be processing the images to identify poorly insulated homes, then sending them back to the owners along with a list of programs and incentives they can use to reduce their heat loss.

If they take advantage, people stand to both conserve energy and save money on their monthly bills, Pander said.

Green building planner Chris Higgins said it's the perfect time for people to think about energy efficiency because for those living in a leaky home, it's a "very visceral" problem.

"If you're missing insulation or if you've got failed windows, you really feel it this time of year," Higgins said.

The program will use a camera-mounted car, similar to those used by Google for its street mapping, to scan homes in the Strathcona, Hastings-Sunrise, Dunbar-Southlands, Riley Park and Victoria-Fraserview neighbourhoods, at an estimated cost of $100,000, or about $6 per home.

Science World is seen in a thermal image provided by the City of Vancouver.

Imaging capturing could start as early as Jan. 15 if the weather is cold and dry enough for the thermal camera, and is expected to last several weeks.

Before that begins, however, the city has promised four public information sessions where people can learn more about the program.

People can also opt-out if they're uncomfortable having a thermal image taken of the outside of their home, Pander added.

"It's very easy to opt-out," he said, adding that "no one has access to the images except the homeowner and [people doing] processing work."

The city has assured that staff will not be allowed to use the images for any other purpose, such as identifying vacant homes, because of privacy laws.

The program, which is similar to others that have been conducted in Detroit, London and Liverpool, is part of Vancouver's Greenest City Action Plan target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 per cent in existing homes and buildings by the year 2020.

Pander said if the pilot project is successful, it will likely be continued next year.

To learn more about the thermal imaging pilot project or to opt out, visit the City of Vancouver website.

The Vancouver skyline is seen in a thermal image provided by the city as it launches a pilot program to identify poorly insulated homes.