There's overwhelming consensus in the scientific community that humans are driving climate change – but depending where in Canada you live, you might not learn that fact in high school.

That's the finding of a new study out of the University of British Columbia, which analyzed the way climate change is presented in textbooks and curriculums from every province and territory in the country.

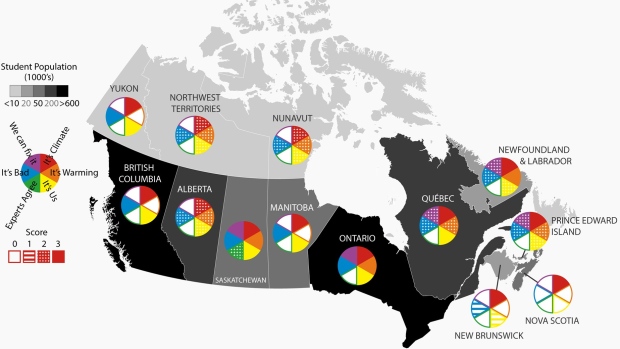

Researchers evaluated the different curriculums based on whether they touched on six core lessons: the way Earth's climate system works, the fact that temperatures are rising, the ways humans are causing it, the fact that scientists widely agree, the negative consequences of global warming, and how we can address it by rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Lead author Seth Wynes, a PhD candidate in UBC's geography department, said while schools generally do a good job of teaching students that humans are to blame for rising global temperatures, most of the lesson plans his team studied failed to convey the fact that the vast majority of experts support that conclusion.

According to NASA, a full 97 per cent of actively publishing climate scientists agree that humans are responsible – yet some Canadian curriculums are unnecessarily wishy-washy, Wynes said.

"It might be something as simple as the phrase, 'greenhouse gases from humans may be causing climate change,' when we know they are causing climate change. There's great scientific certainty," Wynes told CTV News.

Every province and territory fell short in at least one category, and many scored failing marks in half of the six.

Another commonly overlooked lesson was that it's not too late for humanity to reverse the tide, an empowering message that Wynes said could combat climate apathy among students.

Troublingly, the researchers also found curriculums in Manitoba, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador presented human-caused climate change as the subject of debate among experts.

Some lesson plans encourage students to debate the issue among themselves – something Wynes argued is unhelpful in the face of such overwhelming evidence.

"That might be well-meaning, and yet we wouldn't have students debate among themselves whether second-hand smoke causes cancer, because there's great scientific certainty there," he said.

Wynes, who used to teach science in high school, said he felt compelled to study the way Canadian curriculums tackle climate change because it's one of the most important issues today's students will have to contend with in their lifetime.

Yet polling from as recently as 2015 found that 52 per cent of young adults in the country are only "somewhat" or "not at all" concerned about the coming crisis.

Wynes believes more thorough lesson plans could help inspire students to get more engaged.

Interestingly, the team said they found no correlation between a province's reliance on the fossil fuel industry and the quality of its climate change education. Saskatchewan, which has the highest per capita greenhouse gas emissions, had the most comprehensive coverage of the entire country.

"We found no evidence of direct political interference in the writing of these curriculum documents," Wynes said. "No one ever reported politicians saying to the people writing this, 'You must have this statement in your documents.' And that might not be true for all nations, but it's a positive thing for Canada."

While some provinces scored a failing grade on three or more of the core lessons identified by his team, Wynes said a few – including British Columbia – have already updated their curriculums since the researchers gathered the data for their analysis a few years ago.

Considering that some of the lesson plans they studied are over a decade old, Wynes said that's a step in the right direction.

"Things can go out of date. We need to support teachers and the teaching of the scientific consensus – climate change is happening, it's caused by humans and there are solutions if we act quickly."