Almost three years into a public health emergency that has seen thousands die from a poisoned drug supply, a Vancouver agency is trying a new solution: giving patients a clean version of the drugs they normally buy on the street.

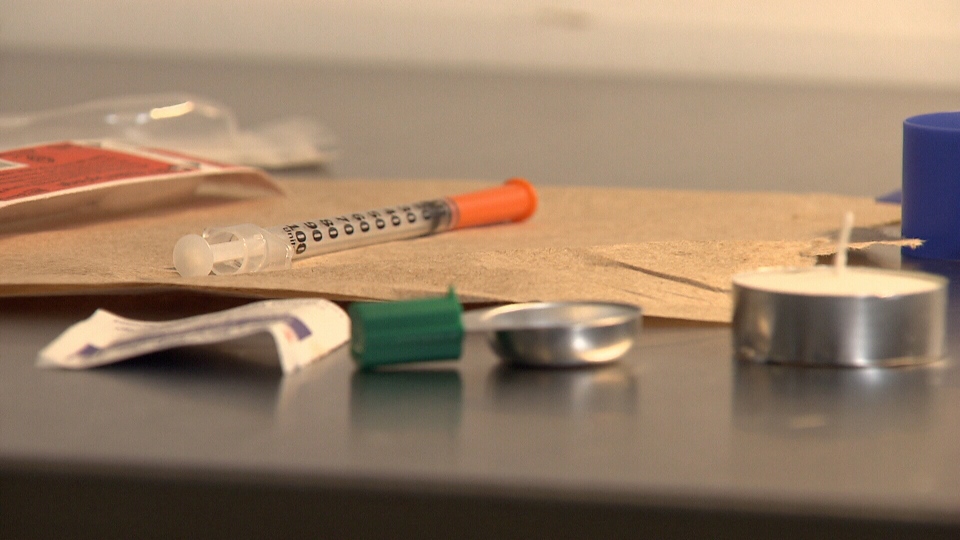

The Portland Hotel Society will offer about 50 patients the opioid hydromorphone in pill form, crush it for them and watch them inject it in an overdose prevention site located steps from the intersection of Main and Hastings streets.

“With the street market in B.C., it’s a totally contaminated market,” said PHS medical director, Dr. Christy Sutherland. “Things that were never meant for human consumption are inside the pills on the street, and people are overdosing on fentanyl.”

The initiative will start Jan. 8 and be set up in the Molson Hotel, a BC Housing building located across a busy alley from the Carnegie Centre.

It’s already the site of an overdose prevention site, of a network of similar facilities where staff watch addicts inject the contaminated drugs and then intervene if they collapse.

But those patients must take risks when injecting and take risks when they have to earn the money to buy the expensive street drugs, said Sutherland.

“My goal is for these patients to exit the street market. They don’t have to be doing illegal things like sex work and have a free supply of safe drugs that and that prevents them from dying of an overdose,” she said.

About 150 patients get access to injectable substitutes, some through Sutherland’s practice and about 100 at the Crosstown Clinic. Those programs cost about $25,000 a year per patient – half the cost to society of the emergency calls and thefts from an untreated addict, studies have shown.

But the therapy doesn’t work for everyone and, just like someone with another medical condition, it’s important to have alternatives, Sutherland said, adding that crushing pills is what most addicts do with drugs they obtained from the black market.

“The idea for the program came from the patients themselves. They would feel better using tablets, so there is some difference that allows their brain to be more comfortable,” she said.

And at about $0.32 a pill, it’s much cheaper than existing programs.

The program is different as the opioids aren’t given out as part of a program designed to wean people from an opioid addiction, but is purely a harm-reduction approach, said Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry.

The program will be studied by the B.C. Centre For Substance Use, she said.

“I think this is an important measure and it’s a start. We need to have a proof of concept so we can make it available to other places as well,” she said.

Hydromorphone pills are designed to be taken orally, and some regulators have been leery of dispensing pills for injection, said Dr. Mark Tyndall of the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

“The natural experiment’s been done across Canada and North America,” he said. “Many of these drugs are crushed and injected. I’m confident that people will use this and find it’s fine, there’s no major health reason not to do this.”

Observing the program could provide evidence to support that, and loosen restrictions that have so far grounded a plan to offer hydromorphone pills through a network of dispensing machines.

Those machines would be secure to theft, identify each patient using some kind of biometric scan, and dispense accordingly.

A public health approach is the best way to stop the deaths, which are now about four a day across B.C.

“If you were being exposed to poisoned milk, we wouldn’t make you go see a physician who would prescribe you with safe milk. We’d address the whole system and come up with a public health alternative,” Tyndall said.

Figures from the BC Coroners Service showed 120 people died of a drug overdose last month, bringing the total this year to 1,380.

Dr. Henry’s predecessor, Dr. Perry Kendall, declared the overdose deaths a public health emergency in April 14, 2016.