Vancouver's mayor says he will direct staff to look for a site where drug users can get safe opioids to prevent overdoses as part of a plan recommended by an emergency task force calling for more services for people who are dying alone.

Kennedy Stewart said the number of overdose deaths has remained about the same as last year despite the best efforts of front-line workers, first responders and health professionals who seem to be fighting a losing battle.

“A long-standing mental health and addictions crisis combined with an increasingly potent drug supply means that unless we take urgent and bold action now, our friends, family and neighbours will continue to die,” Stewart told a news conference Tuesday.

He said he discussed Vancouver's overdose crisis with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau about six weeks ago and he seemed to be sympathetic but the federal government must now provide some funding.

The B.C. Coroners Service recorded 369 deaths in Vancouver last year and by September this year, 297 people had died.

Stewart struck the task force last month shortly after taking office and it includes an addictions physician, housing advocates, first responders, First Nations and drug users' groups.

Its recommendations include a new outdoor inhalation overdose prevention site, which Stewart said is essential because 40 per cent of overdoses are due to people inhaling drugs.

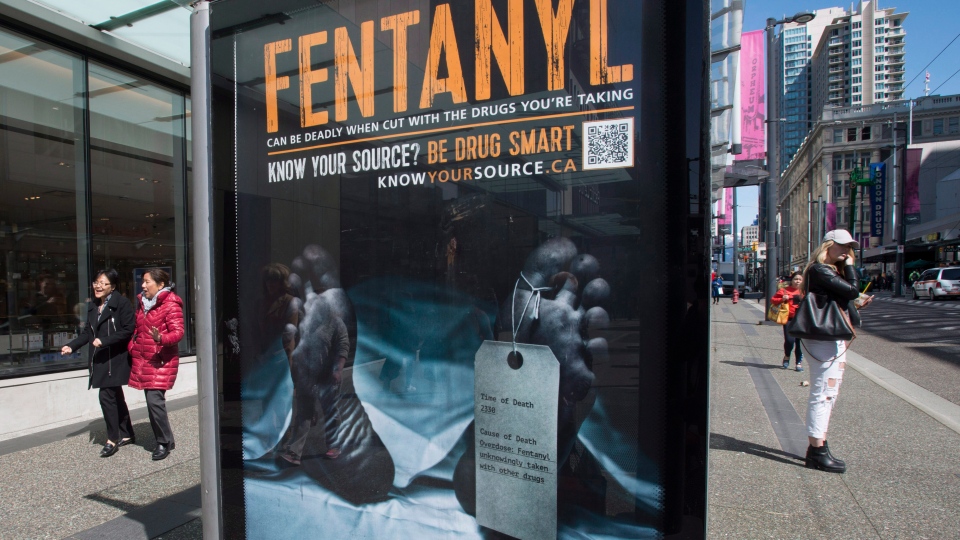

There will be “no end in sight” to the overdose crisis if the toxic drug supply, often tainted with fentanyl, is not addressed, Stewart said, adding the city would provide a site so a federally funded and approved research project headed by the B.C. Centre for Disease Control can go forward. The report says a location should be identified by April.

Dr. Mark Tyndall, the centre's executive medical director, wasn't on the task force but he wants to provide hydromorphone pills early in 2019 and eventually make them available in vending machines.

Doctors are already prescribing the opioid but a public health approach is needed for drug users who typically crush the pills and inject them to get a quick high, Tyndall said in an interview Monday.

“Right now we're asking people to go in back alleys and buy from gangsters and that just doesn't make any sense this far into the epidemic. If the threat of death were enough to stop people from buying these drugs that would have happened by now.”

The centre is working with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. and the province's college of pharmacists to get exemptions from current regulations, Tyndall said.

“It's a very novel idea and it actually goes against what the common narrative is, that there are too many of these drugs out there already and that's what's caused the problem,” he said.

However, Tyndall said the overwhelming number of deaths mean it's time the public and policy-makers have a “switch in thinking” to save lives and reduce crime as people try to access illicit drugs, even if they use them at supervised injection sites.

“This is a public health approach to a poisoning epidemic. This should not be seen as just an extension of treatment to people,” Tyndall said, adding over 22,000 calls involving overdoses were made to 911 operators in British Columbia last year.

Injectable hydromorphone, along with injectable heroin, are already offered at the Crosstown Clinic in Vancouver, but only for about 100 people as part of a model that Tyndall said can't easily be expanded.

Dr. Patricia Daly, the chief medical health officer for Vancouver Coastal Health and a member of the task force, said more people are dying alone in the city than elsewhere in the province because of the high number of single-room occupancy hotels and shelters, and they need alarm systems, apps or other ways to get help.

The report, which calls for nearly $4 million in funding, nearly $2.7 million from the province and the rest from the federal government and the city, will go before councillors on Thursday for approval.

Judy Darcy, British Columbia's minister of mental health and addictions, said it's too early to commit to any money for Vancouver but she supports the recommendations in the report.

“We need to look very closely at where we've already committed funds and where we think we need to expand,” Darcy said, adding many of the city's priorities align with actions the province is working on or has implemented.

The report will help the province to approach the federal government for more funding based on a greater number of overdose deaths in B.C. compared with other provinces, she said.

“The case that we have made and we will continue to make is that means British Columbia should be allocated a disproportionately higher amount of the money. Those are discussions we will continue to pursue with the support of the City of Vancouver.”