Poverty, pavement, isolation: A closer look at B.C. heat deaths

A combination of poverty, scant tree coverage and isolation contributed to the deaths of hundreds of British Columbians during record-breaking heat in 2021, CTV News has learned.

A freedom of information request with the BC Coroners Service for the postal codes where the 619 victims of last year’s heat dome lived resulted in a more precise picture of where they died, though not as detailed as some observers would’ve liked.

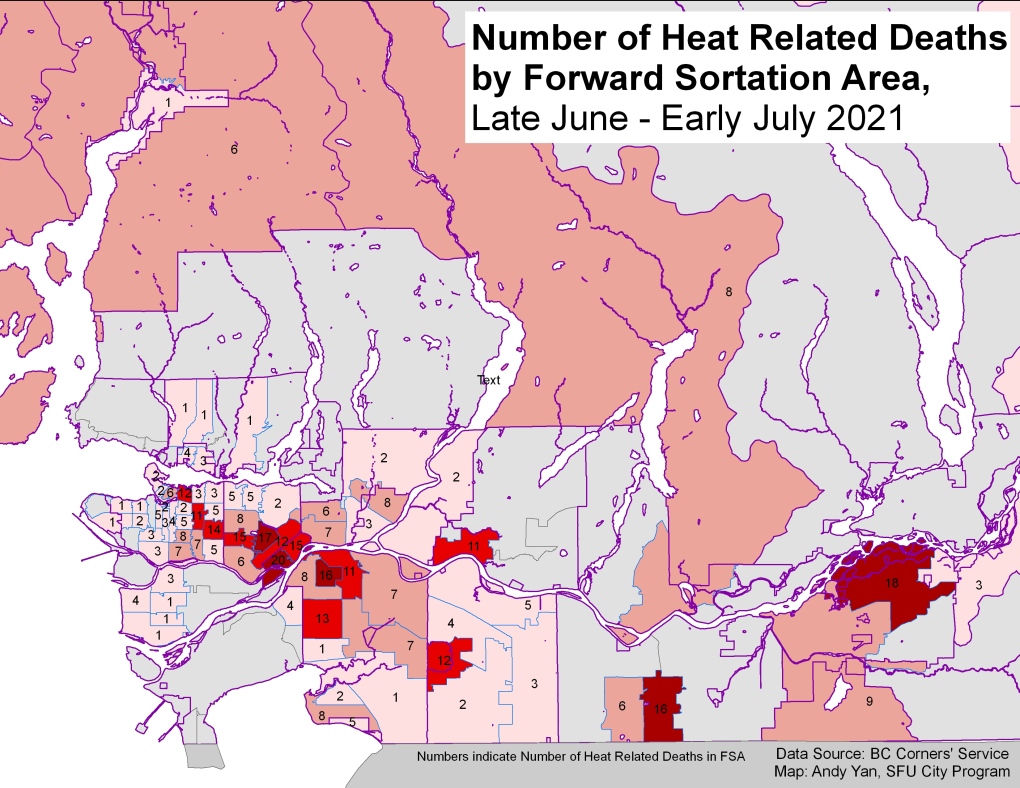

Simon Fraser University's Andy Yan crunched the data exclusively obtained by CTV News and while he wasn’t able to do an effective analysis of income levels or ethnic backgrounds, the demography and urban planning researcher said he was stunned to see which areas saw the highest death rates.

“They were particularly concentrated in very specific areas,” he said, which was information not previously available through the coroner's report.

The postal code data revealed that 18 people died in the most populous area of Chilliwack, with anothernine8 in the rest of the community. In Abbotsford, all 22 deaths were concentrated in areas with subdivisions and townhomes, while all of the 11 deaths in Maple Ridge were between 203rd and 232nd streets. Similarly, Langley, Surrey, White Rock and Burnaby had few deaths outside the more urban sections.

New Westminster was highlighted as having an exceptionally high death toll of 35 people, and when mapped it’s visibly one of the hardest-hit areas. Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, however, only saw 12 deaths.

SOURCE: DATA PROVIDED BY BC CORONERS SERVICE AND MAPPED BY ANDY YAN, SFU

SOURCE: DATA PROVIDED BY BC CORONERS SERVICE AND MAPPED BY ANDY YAN, SFU

DOWNTOWN EASTSIDE SAW FEW DEATHS DESPITE POVERTY

Early on, the BC Coroners Service had revealed that the majority of the deaths were in seniors and those with underlying health conditions, while the final report found 98 per cent of the dead had been indoors.

The chief medical officer for the agency pointed out while a third of those dead had been living in poverty, with about two-thirds living alone or socially isolated, the Downtown Eastside saw comparatively few, which surprised Dr. Jatinder Baidwan and his colleagues.

“That tells us something about when people come together as a group and they’ve got their own social infrastructure set up, they can sort of protect themselves and warn themselves about what’s happening in a trusted way and they can respond better,” he theorized.

When CTV News asked whether the visible poverty in the Downtown Eastside saw more resources and outreach, compared to individuals living alone in unseen, secret poverty, he agreed.

“I think there's a stigma attached to poverty, I think people who are on that terrible line and are ostensibly poor don't want to admit that, don't want to seek they help they could possibly get,” said Baidwan, who is also a practising medical doctor.

“There is a social responsibility to check on your neighbour… we’ve go to knock on doors and make sure that they're OK, and that doesn't come naturally to a lot of us because we sort of respect personal space."

TREE CANOPY AND THE FUTURE

As of now, 16 British Columbians have died from suspected hyperthermia in the summer of 2022 -- half of them in Fraser Health. It’s easy to see on Yan’s map that half of the heat dome deaths were also in that health authority, which services approximately 1.8 million of the province’s 5.1 million residents.

Fraser Health did not respond to a request for an interview on lessons learned and what they’ve done differently this year, though Baidwan believes there have been many improvements – most notably better communication.

He confirmed that urban heat islands with poor or non-existent tree canopies were closely linked to the 2021 deaths, and Yan pointed out that seeing the concentration of deaths and comparing it to tree coverage could provide powerful motivation.

“There's always the correlation-versus-causation discussion, but it really speaks to the effects of the physical environment, the urban environment on heat deaths,” said Yan.

“(Visualizing the deaths through this map) helps inform the public as well as policymakers of the types of interventions and where those interventions should be made to keep our population healthy.”

Correction

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that there were 18 deaths in the most populous part of Chilliwack and 18 in the rest of the community, abut that information has been corrected to nine deaths in the rest of the community.

Additionally, an earlier version said the death toll in New Westminster was 55 people, when it was in fact 35.

The map has also been corrected.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

London Ont. Liberal MPs say that Trudeau is taking time to reflect on his future

Both of London’s Liberal MPs are choosing their words carefully when it comes to their party's leadership future. They were asked about the situation in Ottawa at Friday's housing announcement in London.

Blake Lively accuses 'It Ends With Us' director Justin Baldoni of harassment and smear campaign

Blake Lively has accused her 'It Ends With Us' director and co-star Justin Baldoni of sexual harassment on the set of the movie and a subsequent effort to “destroy' her reputation in a legal complaint.

Trudeau's 2024: Did the PM become less popular this year?

Justin Trudeau’s numbers have been relatively steady this calendar year, but they've also been at their worst, according to tracking data from CTV News pollster Nik Nanos.

New rules clarify when travellers are compensated for flight disruptions

The federal government is proposing new rules surrounding airlines' obligations to travellers whose flights are disrupted, even when delays or cancellations are caused by an "exceptional circumstance" outside of carriers' control.

10 people including children die in stampede in Nigeria at a Christmas charity event

Ten people, including four children, were killed in a stampede in Nigeria's capital city as a large crowd gathered to collect food and clothing items distributed by a local church at an annual Christmas event, the police said Saturday.

Sask. police investigating mischief incident after bomb report in school

Prince Albert police are investigating a mischief incident after a bomb report in a school Friday afternoon.

Wild boar hybrid identified near Fort Macleod, Alta.

Acting on information, an investigation by the Municipal District of Willow Creek's Agricultural Services Board (ASB) found a small population of wild boar hybrids being farmed near Fort Macleod.

Manhunt underway after woman, 23, allegedly kidnapped, found alive in river

A woman in her 20s who was possibly abducted by her ex is in hospital after the car she was in plunged into the Richelieu River.

Calling all bloodhounds: These P.E.I. blood donors have four legs and a tail

Dogs are donating blood and saving the lives of canines at the University of Prince Edward Island's Atlantic Veterinary College in Charlottetown.