On the surface, it seems like a natural conflict: two organizations planning similar events for similar groups of people, one an activist group with a decidedly “outsider” aesthetic, the other a civic institution with broad mainstream appeal.

There are a lot of reasons why the Vancouver Pride Society and the organizers of the city’s Trans, Two-Spirit, and Genderqueer Liberation and Celebration March shouldn’t like each other.

But they do.

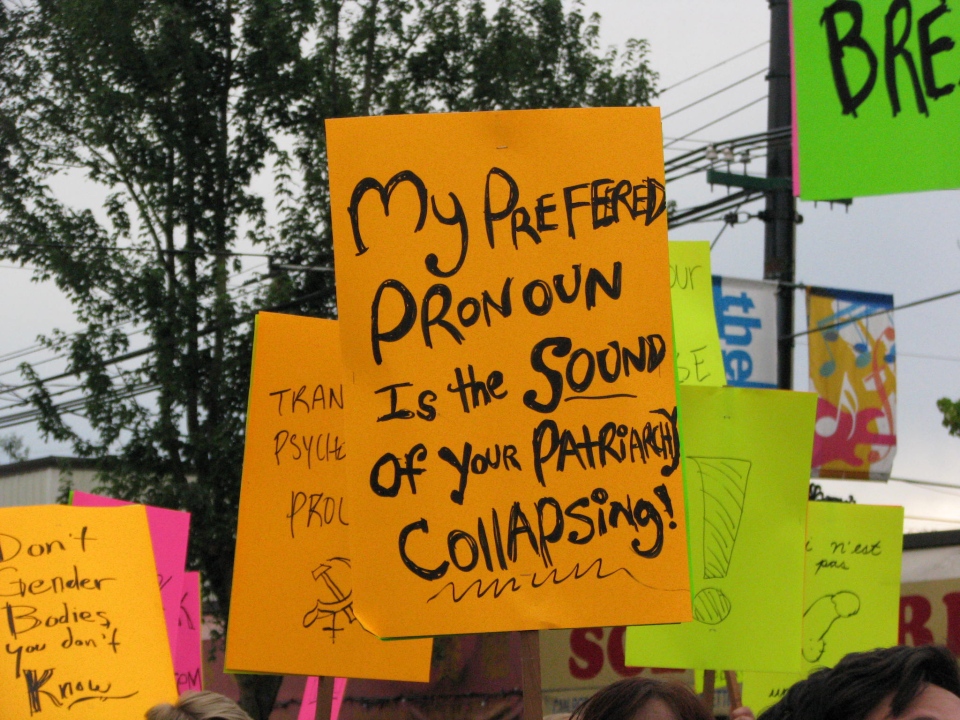

Several members of the pride society’s board and staff participated in the march along Commercial Drive on Friday evening, and “happy pride” was the greeting on the lips of even some of the most radical marchers.

Bry Leckie and Gwen Haworth are two trans women with big roles in this year’s pride festival. Leckie is operations coordinator for the pride society and Haworth is one of the grand marshals for the pride parade. Both spoke highly of the trans march and its organizers.

Similarly, Shannon Blatt and Tara Chee, two trans women involved with the collective that plans the march, said they respect the pride society and appreciate the efforts it’s been making to include transgender people in its festivities in recent years.

Inclusion is something both groups struggle with, and it’s one of the reasons they’re not at odds with each other. They both acknowledge that there’s more work to be done.

‘We need you there’

For the pride society, it’s about changing the historical perception that mainstream pride celebrations are dominated by white gay men. This perception has contributed to the growth of alternative celebrations around North America over the years. Vancouver’s trans march and Dyke March events are good examples of this. Neither is affiliated with the pride society.

Haworth thinks that's a good thing. She said it’s important for “marginalized” communities to organize and represent themselves in the public sphere.

“I don’t necessarily believe that pride should be all-encompassing,” she said. “I think we need to think outside of it too. I think we need to have multiple celebrations.”

Still, improving the inclusion of such groups in pride is important, and Haworth said she believes the pride society is getting better at this.

One of the ways the society does this is by supporting and promoting the trans march and the Dyke March. Both are listed in the calendar of events on the pride society website, and several speakers at the society’s Trans Youth Night at the Rio Theatre on Tuesday expressed excitement for the trans march.

The Trans Youth Night itself is another example of the pride society’s efforts to improve the diversity of its pride week offerings.

Leckie took the lead in organizing the event because of her experience and expertise on trans issues. She said her colleagues in the pride society office aren’t always familiar with those issues, but they’re always interested in learning more about them.

That goes for other groups within the LGBTQ umbrella as well. Leckie said inclusivity is one of the organization’s key goals.

“It’s one thing to say everybody’s welcome, it’s another thing to have groups actually feel like they’re welcome,” she said. “It’s not just a matter of we want you there. We need you there. You enrich the events of the pride society by being there.”

‘Bringing margins to centre’

For the collective that organizes the Trans, Two-Spirit, and Genderqueer Liberation and Celebration March, “inclusivity” has a slightly different meaning, but it’s just as important.

One of the collective’s organizing principles is “the feminist ethic of bringing margins to centre,” according to Chee. That means striving to include and amplify the voices of members of the transgender community who are also members of other minority communities, whether it's because of poverty, ethnicity, or ability.

“It’s a work-in-progress,” Chee said. “It gets better every year, but as a person of colour, I do hope that more people of colour are involved in some way.”

The diversity of the collective’s membership has varied from year to year, Blatt said, but having a diverse group making decisions has always been a goal.

The collective’s commitment to inclusivity is reflected in the formal name of the event it organizes. Some groups wouldn’t differentiate two-spirit or genderqueer people from transgender people.

It's also reflected in the march itself, where the slowest marchers -- often people with disabilities -- set the pace.

Still, the collective thinks it can do more, particularly when it comes to incorporating the most vulnerable members of the transgender community.

Blatt said the group considered holding the march in the Downtown Eastside -- where many of those vulnerable community members live and work -- before moving it to its current location on Commercial Drive.

Continuing the conversation

In many ways, the pride society and the trans march collective are struggling with the same questions. They’re questions that aren’t only relevant around pride week.

A disproportionate number of homeless young people fall under the LGBTQ umbrella, Haworth said. Figuring out how to access them and incorporate them into the broader communities to which they belong is a key goal for the future of those communities.

There are “a lot of conversations” that need to continue, both at institutions like the pride society and informal organizations like the collective, Haworth said.

“It isn’t just the ‘L’ community, it isn’t just the ‘G’ community, it isn’t just the ‘T’ community,” she said. “We have to recognize that there’s a lot of different people that kind of fit within multiple communities, and until we come together and really work with each other and ally with one another, there’s going to be people that fall through the cracks.”

Continued goodwill and increased collaboration between the society and the collective is just one example of the kind of “working together” Haworth is seeking. The goal is to “welcome people in” rather than “call them out,” to “lovingly hold people accountable” when they make mistakes, rather than holding it against them and creating infighting in communities.

With that approach, the future of transgender activism in Vancouver will be exciting to see, Haworth said.

“I feel like in five to 10 years, I will be totally archaic compared to all the amazing stuff that they’re going to be advocating for,” she said. “I’m kind of looking forward to having that glass ceiling shattered over and over again.”