Experts say communities, families critical to determining next steps at Kamloops residential school

Kisha Supernant is first to acknowledge the extreme sensitivity of her work.

The Alberta-based anthropologist has surveyed cemeteries and unmarked burial grounds, graveyards and residential school yards, all in an effort to better understand what may lie beneath.

For Supernant, the director of the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology at the University of Alberta, the discovery of the potential remains of 215 children in unmarked graves on the grounds of the former Kamloops residential school, was simply heartbreaking.

“I can’t say I was shocked or surprised at the news though,” Supernant said, “just because I have done similar work in other contexts.”

In 2019, Supernant and her team used what’s called ground-penetrating radar, essentially what looks like a lawn mower that sends electromagnetic waves into the ground, on the grounds of a former residential school on the Muskowekwan First Nation in Sakatchewan.

Records, she said, indicated between 30 and 35 children were recorded as dying or having gone missing.

With the radar, her team ended up with a preliminary number, between 10 and 15, of what she called “probably grave locations.”

While it’s not clear exactly who is doing the work in Kamloops on the ancestral lands of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, the tools they’re likely using, including ground-penetrating radar (GPR), have limits, Supernant said.

“You do not see the bones themselves, just because they’re not able to be picked up in the wave,” Supernant said. “It’s not like it’s an X-ray.”

Instead, researchers look for disturbances in the soil, an indication of a grave shaft, she said.

And sometimes coffins, when a gap exists between the base and the lid, will also show up, with what Supernant called a “distinctive signature.”

Supernant said findings from GPR can be refined further when overlaid with other technologies, like those using magnets or electrical pulses.

But the only way to be “100 per cent sure,” she said, is to dig.

DECISION TO EXHUME MUST BE LED BY FAMILIES AND COMMUNITIES

Megan Bassendale’s life’s work is identifying human remains and returning them to their families.

Over the past 15 years, she’s worked in conflict-torn areas or in the legacy left behind by war in places like the Balkans, Cyprus, Georgia, and Lebanon.

And while every recovery effort has its unique challenges, she said, they all share something in common.

“The families and the community are a fundamental part of this,” Bassendale, the director of Forensic Guardians Consulting Intl. said. “If they don’t believe in the process then it won’t work. You need to have transparency with them, you need to have buy in from them, and you need to listen to what it is they want.”

The Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc have made it clear, less than two weeks after making the horrific discovery on their lands public, that it is pre-mature to ask or even to consider those questions.

Instead, they have asked those outside the community who want to show their support to “lend a kind ear” and to “truly honour the children.”

Their chief, Rosanne Casimir, said last week she expects a final report detailing the scientific techniques and the findings near the end of June.

While RCMP have opened an investigation into the discovery, it is widely understood that it will be up to the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc, and other impacted First Nations, to decide how much to make public and what to do next.

Bassendale cautioned the process to exhume and identify remains, even should all affected communities be fully onboard, could take years.

“It’s not quick and it’s not easy,” Bassendale said. “And it’s invasive to the families themselves,” she added, pointing to the need to slowly build relationships and, eventually, to collect DNA samples from those who believe they are living relatives of the deceased.

Complicating matters further, the underlying fact there seem to be no records of who the 215 children buried in unmarked graves might be.

INDIGENOUS ARCHAELOGIST: WE MUST HONOUR THEIR WISHES

Paulette Steeves doesn’t want to leave any child behind.

But the indigenous archaeologist, who grew up in Lillooet and knows survivors of the Kamloops school, said ultimately, the decision rests with the impacted communities.

“The first step,” Steeves said, “and it’s up to each community to decide because they all have cultural differences, is to honour the spirits of those children.”

According to the Residential School History & Dialogue Centre at UBC and the National Centre for Truth & Reconciliation, there are over 30 communities whose children were forcibly sent to Kamloops from 1890 to 1978.

Steeves believes every residential school in Canada, even those from the pre-confederation era, should have this work done.

“All of these children deserve to come home,” said Steeves, the Canada Research Chair in Healing & Reconciliation at Ontario’s Algoma University.

But what that looks like, collectively, she said, is up the First Nations impacted.

“This is their decision and their leadership needs be central to this and their wishes need to be honoured,” Steeves said.

Bassendale called it an “all or nothing” decision. “You don’t know who’s where,” she said. “The families will have to decide, what do we want to do?”

Supernant called exhumation “extremely painful and difficult” work.

“Some communities are not going to want to do that,” she said, “And I don’t want them to think that they have to do that to prove there’s burials there.”

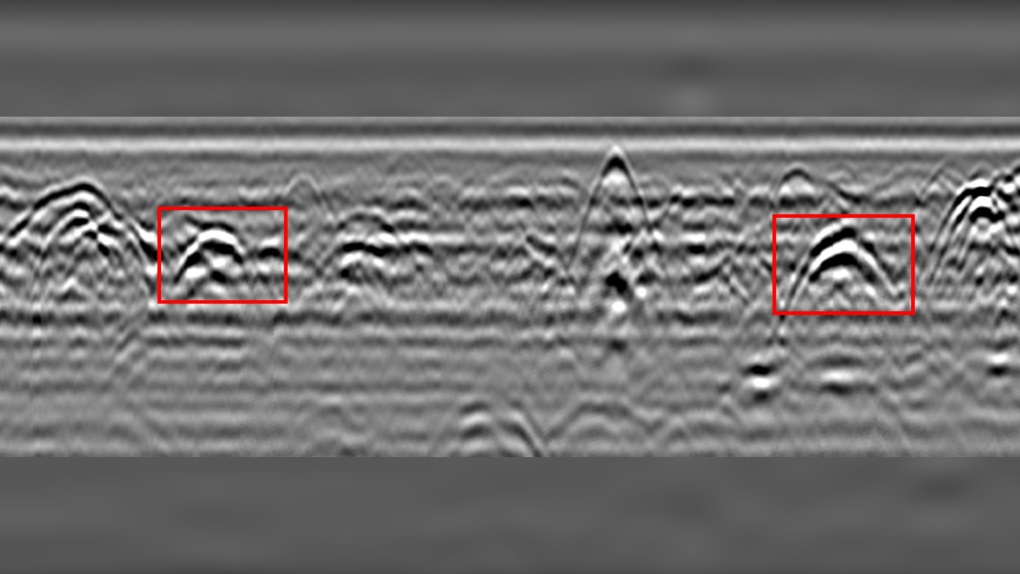

This image shows what graves may look like in radar. The upside-down U-shapes highlighted in red are created by the bottom of the grave shafts. (Liam Wadsworth/University of Alberta)

This image shows what graves may look like in radar. The upside-down U-shapes highlighted in red are created by the bottom of the grave shafts. (Liam Wadsworth/University of Alberta)

This image shows what graves may look like in radar. The upside-down U-shapes highlighted in red are created by the bottom of the grave shafts.

Source: Liam Wadsworth/University of Alberta

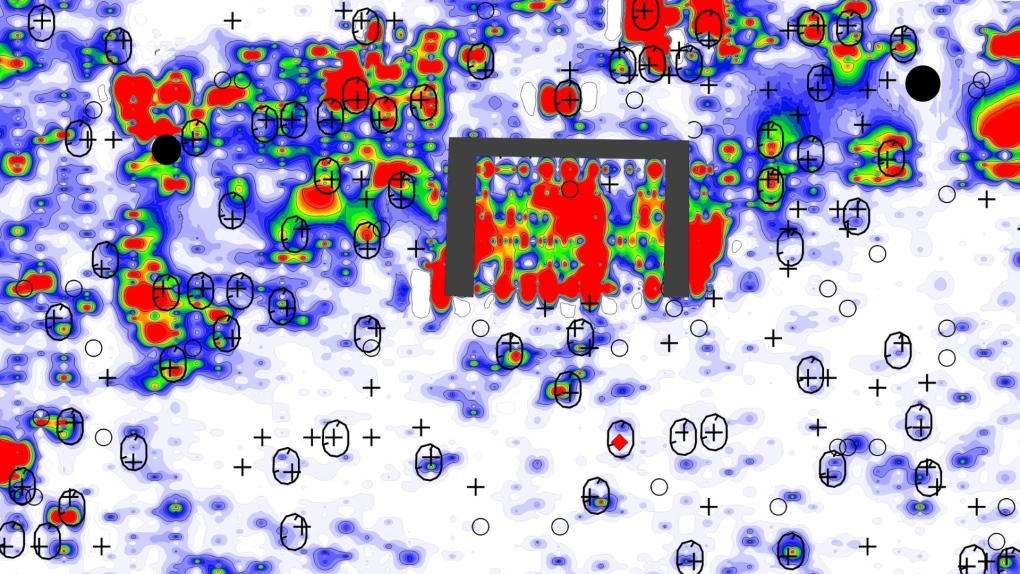

Radargrams can be lined up and processed to produce a top-down image known as a depth map. More colour means a stronger reflection by the ground penetrating radar. (Liam Wadsworth/University of Alberta)

Radargrams can be lined up and processed to produce a top-down image known as a depth map. More colour means a stronger reflection by the ground penetrating radar. (Liam Wadsworth/University of Alberta)

Depth Map (Colour)

If you are a former residential school student in distress, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419

Additional mental-health support and resources for Indigenous people are available here.

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Fall sitting bookended by Liberal byelection losses ends with Trudeau government in tumult

The House of Commons adjourned on Tuesday, bringing an end to an unstable fall sitting that has been bookended by Liberal byelection losses. The conclusion of the fall sitting comes as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's minority government is in turmoil.

2 B.C. police officers charged with sexual assault

Two officers with a Vancouver Island police department have been charged with the sexual assault of a "vulnerable" woman, authorities announced Tuesday.

Canadian government announces new border security plan amid Donald Trump tariff threats

The federal government has laid out a five-pillared approach to boosting border security, though it doesn't include specifics about where and how the $1.3-billion funding package earmarked in the fall economic statement will be allocated.

B.C. teacher disciplined for refusing to let student use bathroom

A teacher who refused to let a student use the bathroom in a B.C. school has been disciplined by the province's professional regulator.

Most Canadians have heard about Freeland's resignation from Trudeau cabinet, new poll finds

The majority of Canadians heard about Chrystia Freeland's surprise resignation from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's cabinet, according to a new poll from Abacus Data released Tuesday.

Police chief says motive for Wisconsin school shooting was a 'combination of factors'

Investigators on Tuesday are focused on trying to determine a motive in a Wisconsin school shooting that left a teacher and a student dead and two other children in critical condition.

After investigating Jan. 6, House GOP sides with Trump and goes after Liz Cheney

Wrapping up their own investigation on the Jan. 6 2021 Capitol attack, House Republicans have concluded it's former GOP Rep. Liz Cheney who should be prosecuted for probing what happened when then-President Donald Trump sent his mob of supporters as Congress was certifying the 2020 election.

Wine may be good for the heart, new study says, but experts aren’t convinced

Drinking a small amount of wine each day may protect the heart, according to a new study of Spanish people following the plant-based Mediterranean diet, which typically includes drinking a small glass of wine with dinner.

The Canada Post strike is over, but it will take time to get back to normal, says spokesperson

Canada Post workers are back on the job after a gruelling four-week strike that halted deliveries across the country, but it could take time before operations are back to normal.