VANCOUVER -- Health officials in British Columbia have released new modelling data that reveals where the most common strains of COVID-19 circulating in the province came from.

On Thursday, provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry shared what's known as genomic epidemiology, the tracing of the virus's movements that's made possible by RNA sequencing at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

"This is some really leading edge work," Henry said. "This is the first time that we've been able to rapidly sequence genomes to help us understand the trajectory of our pandemic in a very short period of time."

- Dr. Henry responds to restaurant owners urging her to encourage dining out

- 9 new cases of COVID-19 in B.C., but some are from previous weeks

- Should you book that summer vacation? B.C.'s top doctor weighs in

- New machine set to improve Fraser Health's COVID-19 testing capacity

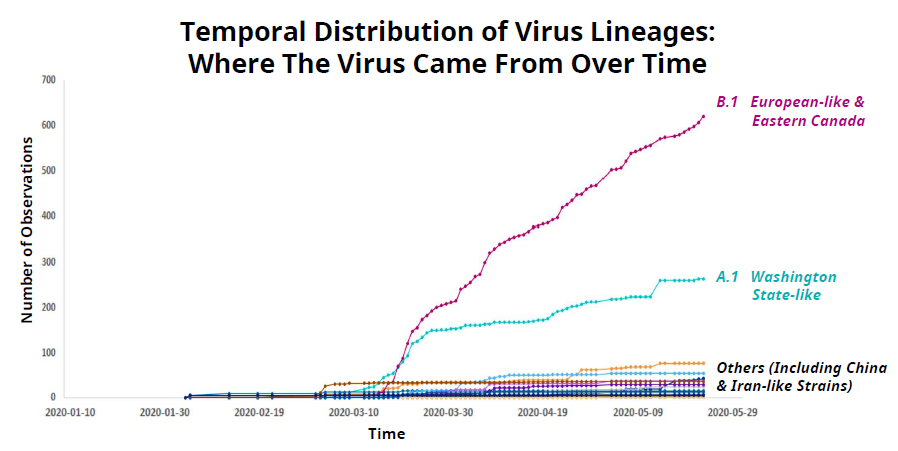

The results show that while early cases of the novel coronavirus that emerged in January and February were linked to China and Iran, those strains were successfully contained and quickly surpassed in March by what officials referred to as "European-like and Eastern Canada" strains and "Washington state-like" strains.

Henry noted that of the 2,632 test-positive infections identified in the province so far, only about 700 cases have been fully sequenced, but she said the results they've collected provide a good indication of the trajectory of the various strains.

The tracking shows how the virus was introduced into B.C., but all strains, as far we currently know, originated in Wuhan, China.

The greatest number of cases, by far, have been linked to the European and Eastern Canada strains. Officials said those cases took off following a March 6 dental conference in Vancouver that resulted in dozens of new infections and at least one death.

"The viruses that we were seeing that came out of that conference reflected their European origins, and they were more closely related to virus sequencing that we were seeing in Germany, Italy and France," Henry said.

There were also multiple introductions of the virus from people who carried it into B.C. from Washington state. Similar strains of the virus that came from other parts of the U.S. have been lumped in with those, which is why they are called "Washington state-like" in the tracking.

This kind of tracking works because COVID-19, like all viruses, changes over time. Dr. Henry said it doesn't mutate as quickly as influenza, but does mutate fast enough to make the genomic epidemiology tracing possible.

"We can tell where it's come from by how many changes there are in the genetic pattern, and then we share those around the world and we compare and we can see where somebody may have originated, or where the virus may have originated, that then came into British Columbia," Henry said.

Geographically, officials have found Washington state-like strains make up almost 75 per cent of the cases identified in the Vancouver Coastal Health region that spans from Richmond up through Whistler, while the European-like and Eastern Canadian strains make up about half of the cases identified in the Fraser Health region that spans from Burnaby to Hope.

The most serious cases of COVID-19

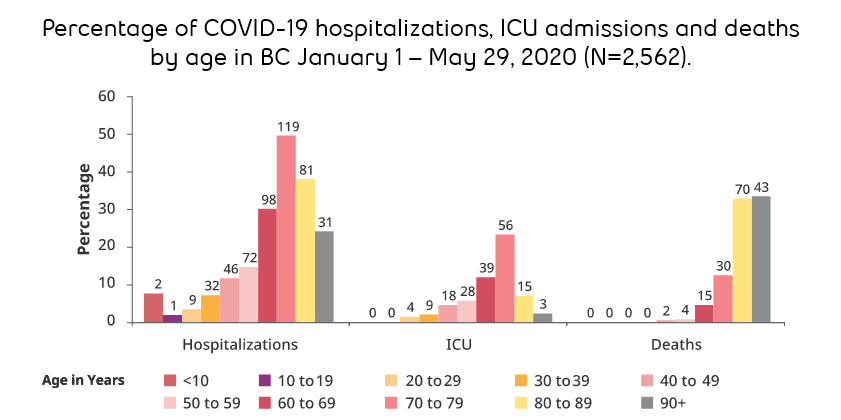

Officials also provided an update on the most serious infections detected in B.C., the ones leading to treatment in hospitals and intensive care units as well as deaths.

The numbers show that so far, no one under the age of 40 has died from COVID-19. Six people between the ages of 40 and 59 have succumbed to the virus, as have 45 people between the ages of 60 and 79.

The vast majority of fatalities – 113 of the 166 deaths recorded so far in the province – have come from people over the age of 80.

A number of young people have been hospitalized, however. Twelve people under the age of 29 have had to be treated in hospital for their infection, including two children under the age of 10.

Those young children who were hospitalized make up about seven per cent of all kids in that age group who have caught the virus, Henry said.

Four people between the ages of 20 and 29 have been sick enough to need treatment in the ICU.

But similarly to fatal cases, most of the infections serious enough to require treatment in hospital and ICUs, by far, have involved seniors.

Officials also continue to see many more men – about two-thirds of cases – hospitalized and killed by the virus.

"This is something that we've seen in many other countries," Henry said. "We've talked about the biological reason why this might be. We still don’t have all the answers to that yet."

Comparing B.C.'s pandemic to other jurisdictions

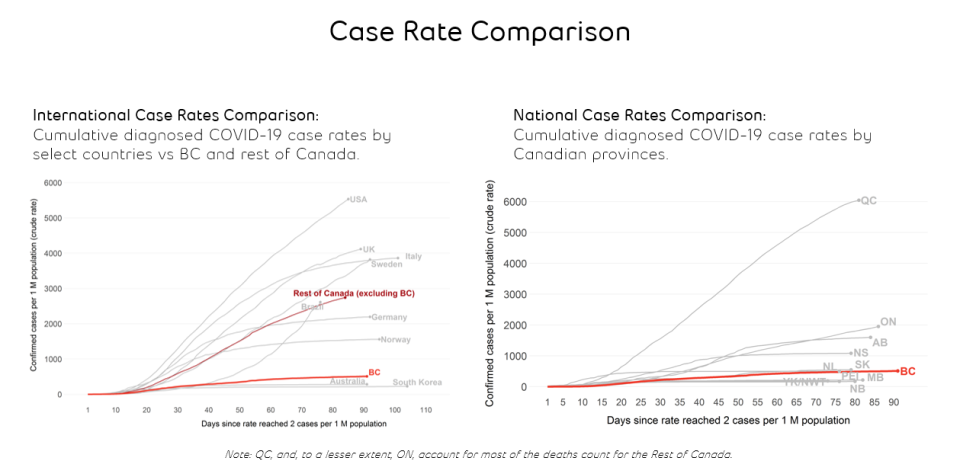

The latest modelling also compares British Columbia's case rates and death rates to other jurisdictions, and shows the province faring better than most countries and Canadian provinces.

When it comes to infection rates, which are measured in cases per million residents, the numbers show B.C.'s rate is lower than every compared country except Australia and South Korea. The province is also doing better than Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland.

The results were similar when comparing the rate of fatalities.

"We have, by the work that people have done here in B.C., maintained a very flat case rate comparable to many other countries in the world and certainly compared to many of our other provinces," Henry said.

The results indicate that physical distancing and other precautionary measures undertaken in B.C. have had a clear and beneficial impact on its caseload. Maps comparing the different areas of the province throughout the pandemic to the past 14 days shows dramatic decreases in cases.

As of Thursday, there are just 201 active cases of COVID-19 across B.C., the lowest it's been since March 17, and recoveries have steadily outpaced new infections for weeks.

Public health investigations over time

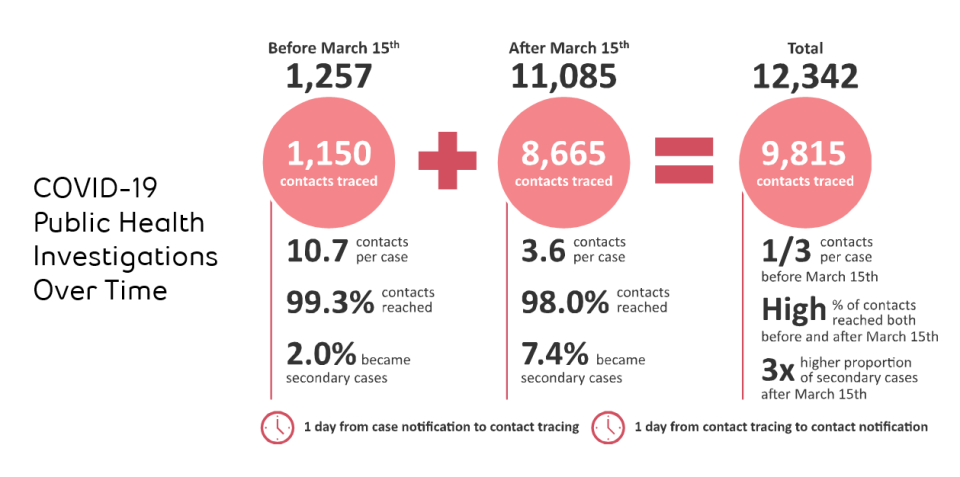

Officials also shared numbers on the ongoing contact tracing investigations done by health workers to contain community spread after new cases are confirmed.

Prior to March 15, which is around the time that the province asked people to stay home as much as possible, every time a new case emerged, investigators had to reach out to an average of 10.7 contacts. Of those, two per cent became infected.

Since March 15, investigators have only had to track down an average of 3.6 contacts per new case. Of those, 7.4 per cent became infected, a reflection of the fact that most contacts were from the same household.

A total of 1,150 contacts were traced prior to March 15, and 8,664 have been traced since. During the entire pandemic, officials said it has taken about one day to notify people that they had potentially been exposed to the virus after contact tracing efforts began.

Earlier on in the pandemic, when testing supplies were limited, only certain people were tested, including those who work in high-risk professions or were seriously ill.

People whose symptoms were mild were often just told to self-isolate, and considered "epi-linked" cases, a presumption that they likely had the virus.

Going forward, now that supplies are more readily available, Dr. Henry said officials will be reaching out to those "epi-linked" cases and doing serology testing to determine whether they were, in fact, carrying the coronavirus.

The regular virus briefings from Henry and B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix will include newly confirmed epi-linked cases from now on, officials said.

Read through the province's presentation below.