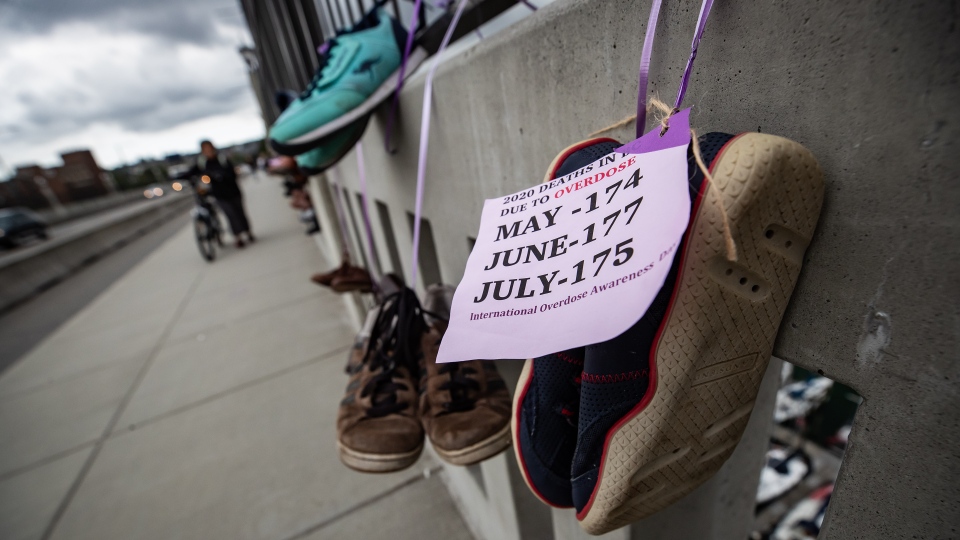

VANCOUVER -- Last year was British Columbia's deadliest on record when it comes to illicit drug overdoses, the province's chief coroner says.

In an update Thursday, Lisa Lapointe announced 1,716 people died in 2020 due to toxic illicit drugs.

It's a 74 per cent increase over the 2019 death toll of 984, making 2020 what the coroner's service calls the "worst year yet" in terms of overdoses.

Lapointe said it equates to 4.7 deaths per day, which is two deaths a day higher than in the previous year.

"This represents the most deaths ever in a single year in this province due to an unnatural cause, and an alarming death rate of 33.4 per 100,000 people," she said.

Deaths due to drug toxicity "far surpass" the number of deaths due to suicides, car crashes, homicides and prescription drugs.

In fact, illicit drug overdoses surpass the deaths from all of those other causes combined, Lapointe said.

B.C. declared a public health emergency nearly five years ago, following a spike in deaths.

Lapointe called it a "terrible burden of death" due to a toxic supply.

She said when B.C. reaches the anniversary of the emergency in April, nearly 7,000 people will have died.

"These are sons, brothers, fathers, daughters, sisters, friends and colleagues. Thousands of years of life and potential are gone," she said.

"We must turn this terrible trajectory around."

A photo collage created by the group Moms Stop the Harm and shared by the B.C. Coroners Service shows some of the British Columbians who have died of illicit drug overdose.

Last year's deaths followed what she described as a pattern throughout the emergency: the majority are dying inside private residences.

Most are men, and between the ages of 30 and 59.

The communities that saw the highest toll in 2020 were Vancouver, Surrey and Victoria.

But Lapointe said the deaths aren't confined to certain areas or populations.

"People are dying in communities across B.C., from all walks of life, and leaving behind broken-hearted families, friends and colleagues," she said.

Mapping data shows virtually no areas of B.C. are untouched, she said. The majority of B.C. is seeing death rates of more than 30 per 100,000 people.

Fentanyl and its analogues were found in more than 80 per cent of fatal cases. Looking at a five-year period, it's been in more than 86 per cent of deaths, the chief coroner said.

Cocaine and methamphetamine are the next most common substances found in people who have fatally overdosed in B.C., she said.

Lapointe said the data show the impact of COVID-19 on those facing substance use challenges in B.C.

Throughout 2020, doctors and first responders spoke out about the challenges created by the pandemic.

With borders closed, some local dealers were making their own supply, meaning users were getting inconsistent doses.

Additionally, many were using alone due to physical distancing guidelines, or were less likely to go to hospital for fear of contracting the novel coronavirus.

Lapointe said harm reduction measures including supervised injection sites and drug-testing sites are reducing overdoses in 2019, but access has been limited during the pandemic.

"The harms associated with the illicit drug market returned with a vengeance."

"Decades of criminalization, an increasingly toxic illicit drug market and the lack of timely access to evidence-based treatment and recovery services have resulted in the loss of thousands of lives in B.C." Lapointe said.

"It's clear that urgent change is needed to prevent future deaths and the resulting grief and loss so many families and communities have experienced across our province."

Speaking after Lapointe, B.C.'s minister of mental health and addictions acknowledged the toll the crisis has taken on others as well.

"Front-line workers, families and peers responding to overdoses and caring for loved ones during the pandemic are heroes, and our province is grateful for their compassion under immense strain," Sheila Malcolmson said.

She said the ministry stepped up its response in the past, but the supply has become "dramatically more toxic" in the last year.

Malcolmson said the ministry is committed to building "culturally safe, evidence-based systems," but acknowledged there is more that can be done.

She said the ministry will add more treatment beds and recovery options, and will work with its federal counterparts toward decriminalization to save lives.

The minister called decriminalization a vital step toward saving lives due it its impact on stigma.

"Whether it's Canada-wide or in B.C., it is in the federal government's power to act," she said.

Decriminalization was also part of the message from Vancouver Mayor Kennedy Stewart, who spoke to media the same day.

His city saw 408 deaths last year, and more than 2,100 in the last decade.

Stewart called the coroner's report "shocking," and urged the public to see beyond the numbers to the people impacted by the deaths.

"Think about all the people those lives touched. All the parents, siblings, children and friends," he listed.

"We mourn the loss of these loved ones who are victims of a long-standing mental health and substance use crisis and a consistently poisoned drug supply."

Like Malcolmson, the mayor reiterated his calls for the federal government to grant an exemption for decriminalization in the city.