VANCOUVER - Fishing activity is choking the delicate glass sea sponges along British Columbia's northern coast and an expert says the sediment risks killing "a kaleidoscope" of wildlife if they die off.

A study published recently in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series says activities such as bottom trawling, where a weighted net is dragged across the sea floor, can smother the sponges by clogging their internal filtration system.

The authors include biologists at the University of Alberta who studied three species of glass sponges found at depths from 30 to 200 metres in the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound.

"A range of other species of animals also live on the reef so it's like a kaleidoscope, a forest, a jungle in there," co-author Sally Leys said in an interview on Monday.

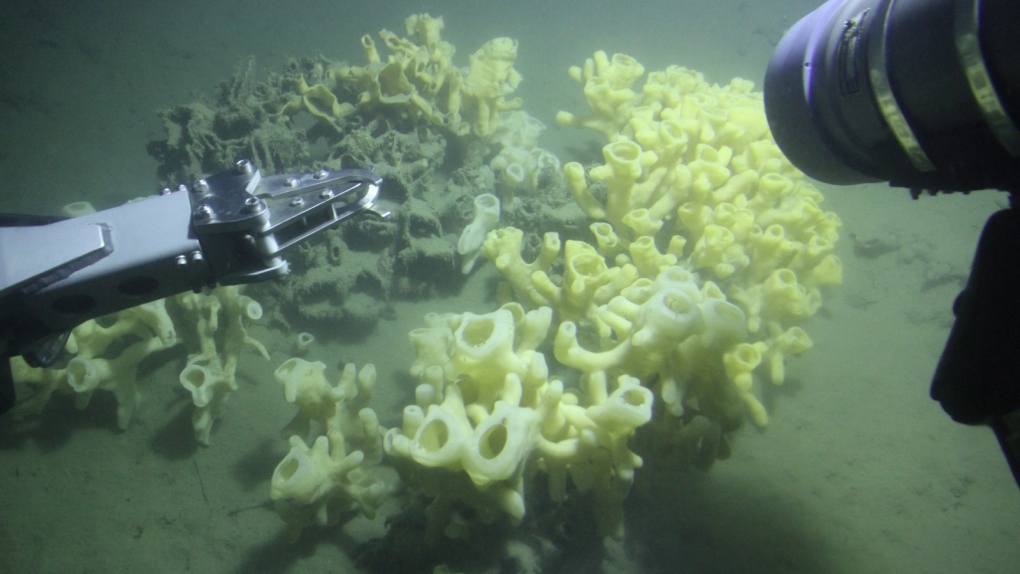

"They are an unusual flower-like animal that feeds on tiny particles in the water, so they clean the water."

The sponges have a delicate skeleton of glass, which is covered by a thin layer of creamy white skin, she said, adding that they come in a variety of shapes that look like goblets or vases.

The study says the sponge reefs also provide extensive habitat for many commercially important fish and invertebrates, such as Pacific halibut, rockfish and spot prawn.

In February 2017, Fisheries and Oceans Canada established a 2,410 kilometre protected area around four glass sponge reef complexes in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound.

Leys said the aim of the study was to determine whether activities outside the boundaries of the marine protected areas affect the animals inside.

The study suggests the boundaries of the marine protected areas be expanded up to six kilometres to further protect the sponges, she said.

"Trawling has been going on for a very long time, probably a hundred years, but with our increased technology the ships can use larger nets and can reach deeper," Leys said.

The sponges have an electrical conduction system that sends a signal essentially shutting down their breathing when a fish or a tide kicks up sediment, she said.

"That is the best protection they've got - to hold their breath," she said, adding that the protective mechanism is what might kill them.

The paper said the sponges also face other problems, such as warming temperatures, food availability and ocean acidification.

The reefs are about 6,000 years old and the sponges are hundreds of years old, Leys said.

"It takes hundreds and hundreds of years, and thousands for these to form, so they will die off and with it, habitat that will no longer support everything that goes with it," she said.

"They won't come back in our lifetime."