The recent sale of two cedar masks considered culturally sacred to a Vancouver Island First Nations family has prompted a university instructor to ask the provincial government to change the law affecting cultural property.

Members of Port Alberni, B.C.'s Hamilton and Sayers families say they plan to strip the family member who sold the "hinkeets" of her royal title and cultural responsibilities at an upcoming ceremony, shedding light on the internal disciplinary proceedings practised by First Nations for generations.

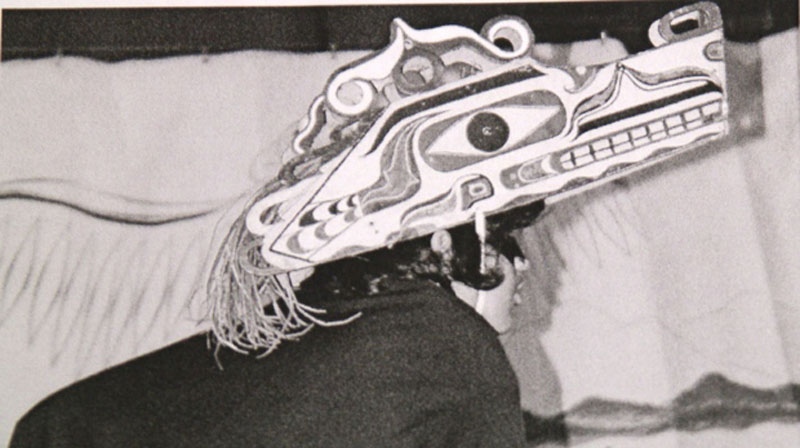

The masks were more than 100 years old, depicted male and female serpents and had been passed down along the maternal lines of the family for safe keeping. But they were auctioned off in November to an unknown buyer for $4,000 and $22,500.

"We just have to take care of business," said Judith Sayers, a former elected chief for the Hupacasath First Nation who lectures in law and business at the University of Victoria.

The family member responsible for the masks was out of the country and could not be reached for comment.

Sayers said she recently told a working group of First Nations leaders and provincial government representatives that B.C.'s Heritage Conservation Act doesn't address the sale of similar items.

Sayers has said the masks were "cultural property" owned by the family. The individual who sold them inherited them in a will governed by provincial law that recognized individual ownership.

As a result, said Sayers, a legal and cultural clash has developed over collective and individual rights.

The Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, which oversees such cultural issues, confirmed a working group exists to deal with "all aspects of First Nations heritage conservation," and the government is willing to talk.

"If the First Nations Leadership Council is supportive of continued work through the working group, we are prepared to identify further potential changes to portions of the act, subject to public consultation and legislative approval," the ministry stated in an email to The Canadian Press.

Karen Duffek, a curator at the University of British Columbia's Museum of Anthropology, agrees there's a problem.

"The legal ownership that the owners of those particular Nuu-Chah-nulth pieces had is recognized by our legal system, but it's not the same definition of ownership that is the Nuu-chah-nulth one."

While demand has existed for First Nations masks and other cultural symbols since Europeans arrived on the West Coast, the market grew in the 20th century, especially when museums and art galleries began to collect and exhibit the work, said Duffek.

"I think that masks, there's a certain appeal to them internationally, no matter where they're from," she said. "There's a strong interest in masks and a huge range in characters being represented and artistic styles."

But the masks aren't just art because "intangibles," such as rights, privileges and responsibilities, are attached to them, she said.

Wawmeesh Hamilton, a member of the Hupacasath First Nation and a cousin of Sayers, said he learned about the auction when he was tipped by a relative.

The masks, he said, were accompanied by shawls and even a specific dance and were handed down to his mother, Jessie Hamilton, who died in 2008, before they were again passed on.

He said the masks were only brought out during potlatches.

"This can't go unanswered in so far as consequences are concerned," he said, noting the family holds a cultural responsibility to correct the sale.

"There has to be a series of consequences that are meted out."

Since the auction was public, the consequences and discipline must be public, he added.

The family member who sold the hinkeets will be stripped of title, name and cultural responsibility, actions Hamilton said were much like a "shunning" in western culture.

"That's like being dead while alive," he added.

The discipline could take place during a potlatch planned for November or December, although Sayers said it could be handed out much sooner.

Regardless of when or where it happens, Sayers said discipline could come during a gathering or meal, attended by local chiefs, and could be as simple as an individual rising to discuss "business."

Hamilton said the family is still trying to locate the masks. If they are successful and can regain ownership, they will show them during the potlatch in the fall.

If not, the family will unveil new replacement masks, explain what happened and transfer the related song, dance and ceremony to the new hinkeets.

"We're not the only members of the family, we're not the only generation that potlatches," he said.

"Our kids are going to have kids and they're going to require names. There will be marriages where this is brought out. So their use will go on unbroken."