OTTAWA -- Atlantic herring is a hearty source of protein for people and marine mammals alike, but like a startling number of Canada's fish stocks the plan to rebuild the depleted herring population is currently one big question mark.

That's a conclusion reached by advocacy group Oceana Canada, which published its second annual fisheries audit Tuesday -- a report card assessing the health of Canada's fish stocks.

The report found Canada has a lot of work to do to reverse the term decline of its fish stocks, and it needs to pick up the pace.

Oceana's science director Robert Rangeley said he hopes the audit is a "wake-up call" for better fisheries management.

"My biggest fear is one of complacency," said Rangeley. "We're still hovering around one-third of our fish stocks (that) are healthy, which is very poor performance for the 194 stocks that are so important for coastal communities."

- Download the full report as a PDF

Only 34 per cent of Canada's fish stocks are considered healthy. Twenty-nine per cent are in a critical or cautious zone, and perhaps most alarmingly, 37 per cent of stocks don't have sufficient data to assign a health status.

Some, like Pacific herring in Haida Gwaii, slipped into the critical red zone this year.

The numbers are indicative of the slow policy implementation that plagues management of Canada's fisheries, Rangeley said. The Oceana team expected to see more stocks move from the uncertain zone into one of the other categories this year, but in fact, the needle barely moved.

Rangeley said government transparency has improved in recent years, giving his team access to the audit's necessary data. But scientific reporting and assessment of stocks is slow and incomplete. Scientific and planning documents are often published late, or not at all.

Slow scientific publication means some stocks haven't been assessed in years -- and with the impacts of climate change affecting the ocean at a swift pace, it means some of the health assessments are becoming too outdated to plan around how to help improve the stock.

Of the 26 stocks that are assessed as critically depleted, only three have rebuilding plans in place. And even when those plans are published, the report notes that they are often based on out-of-date scientific assessments.

Atlantic Canada's fin fish are most heavily represented among the critical stocks.

Rangeley said invertebrates like lobster and crab are more likely in good health than at-risk fin fish like cod and herring. However, rebuilding plans to bring struggling stocks back to health are notoriously slow to appear.

Perhaps the most famous example is the infamous cod moratorium in 1992 that devastated Newfoundland's fishing communities. Twenty-six years on, there's no plan in place to rebuild the Northern cod stock.

It's not just an issue for the depleted stocks, said Rangeley. He recommends that a sense of urgency is applied to stocks in the cautious zone as well as the critical zone, because the more depleted they get, the harder it is to rebuild.

"It's just a biological reality," Rangeley said. "Knock 'em down too far for too long, the effort takes so much longer and it's such a lost opportunity for a valuable seafood industry to just let such a waste occur."

Striking the balance between a healthy ocean ecosystem and an economically viable, renewable food industry for small communities is not impossible, and it's been done before, said Rangeley.

To run the fisheries right, more vigilance is required, the report said.

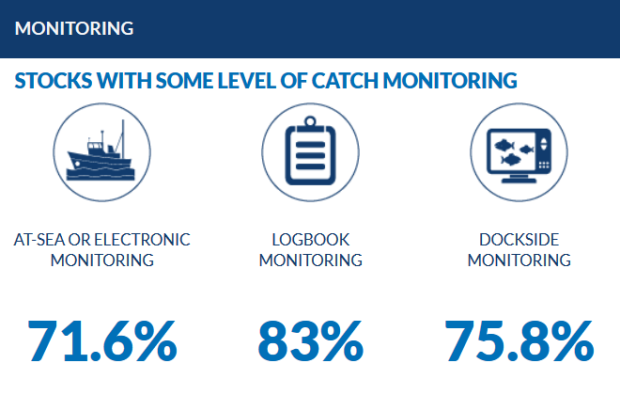

Some form of catch monitoring is in place for more than half of Canada's stocks but the methods often don't give a complete assessment of the catch, leading to big data gaps. And 159 stocks don't have fishing mortality estimates, making it nearly impossible to set sustainable limits on the industry.

The report recommends investing in science and management capacity, assessing stocks regularly and developing up-to-date, well-enforced rebuilding plans.

It also highlights the importance of timely reporting, and calls for a national 'fishery monitoring policy' that would compel all commercial fisheries to sufficiently keep track of yearly catches.

Good planning, Rangeley said, is essential to getting Canada's fisheries back to a healthy, sustainable level for oceans and for people.

"You can sustainably harvest seafood indefinitely if you get it right, and we're not," he said.

By Holly McKenzie-Sutter in St. John's, N.L.

All graphics from Oceana Canada's report.