On the second floor of an immigrant settlement agency in Richmond, B.C., Gigi Lo delivered her first presentation on hepatitis C and HIV to a class of English as a Second Language students Wednesday.

The United Chinese Community Enrichment Services Society, or SUCCESS, sits in a new building near the Richmond Centre mall. That day, late spring sunshine poured into the classroom through its floor-to-ceiling windows.

Delivering communicable disease education in an ESL class is clever because it’s non-threatening. No one needs to seek out a workshop focused on hepatitis C, it’s just framed as part of the curriculum and an opportunity for students to brush up on their medical vocabulary.

One student, Jasmine Yaying Weng, had a glossary of words like “treatment” written in English and Chinese in her notebook.

Gigi Lo, manager of SUCCESS’ HIV and hepatitis C intervention project, delivers education about the viruses and helps connect new arrivals to health care.

The session went over how hepatitis C is transmitted, how to get tested and risk factors. There can be a stigma attached to the illness, likely stemming from hepatitis C’s prevalence among injecting drug users. But at the workshop, Lo explained people often contract hepatitis in Asian countries from improperly sterilized medical or dental equipment.

She also went over problems like language barriers and a lack of health insurance as reasons why newcomers sometimes don’t get tested or seek treatment.

It’s all part of a pilot program spearheaded by a Vancouver doctor to connect people in immigrant communities with hepatitis C care.

Dr. Alnoor Ramji, a liver specialist, says now that drugs to treat hepatitis C are covered publicly in B.C., the next step is to actually get patients treated.

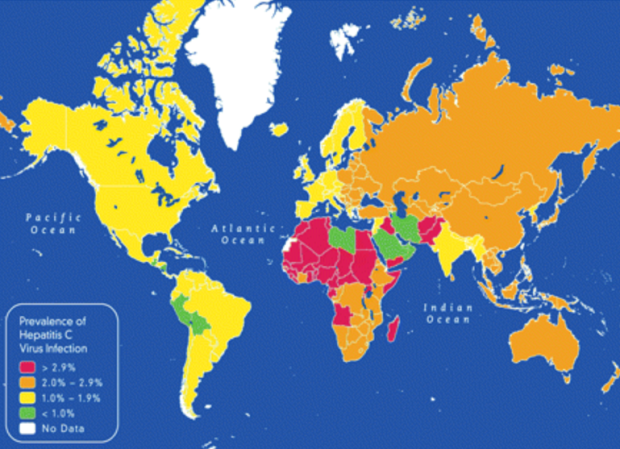

He’s paying particular attention to people coming to Canada from countries where the liver-targeting virus is endemic, because people may not even know they have it.

“When they do come to Canada they're not actually seeking care for almost a decade later. So these people will unfortunately present with more advanced liver disease and potential complications.”

Dr. Ramji’s community partners are delivering hepatitis C education in various languages in regular workshops offered for newcomers.

If left untreated, hepatitis C can cause cirrhosis (liver damage) and liver failure. Unlike hepatitis A and B, there is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

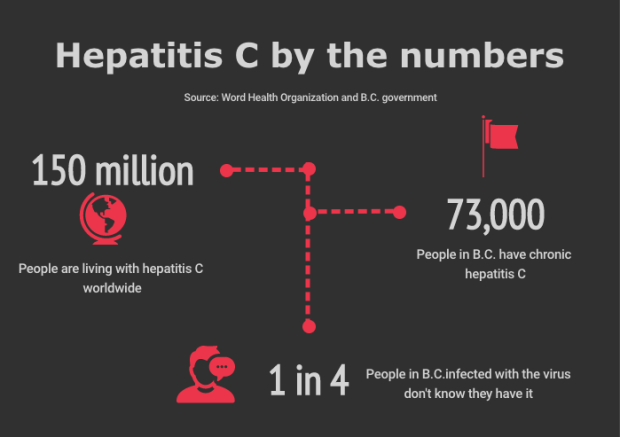

The World Health Organization estimates there are up to 150 million people living with the virus worldwide. About 73,000 of those are living in B.C. One in three of those people is foreign-born.

In the province, somewhere between 25 and 44 per cent of people who are infected don’t know they are.

Queenie Choo, CEO of SUCCESS, said she wants to make sure people are given resources in their language to make sure they understand that the potentially deadly virus is “absolutely treatable.”

Direct-acting antivirals, a highly effective cocktail of drugs, can cure hepatitis C in 95 per cent of cases. Doctors can even tailor the regimen to suit the genome of a person’s virus.

But until recently, those drugs were prohibitively expensive. One round cost $45,000-$50,000 and the government would only fund it for patients with severe liver damage. But that all changed in March 2018 when B.C. followed Ontario to extend public coverage of the pharmaceuticals to anyone diagnosed with the virus.

"So [now] there's no reason for any of us to not get treatment or not get tested because of cost,” Lo said, driving home how important it is to get tested given there’s such an effective cure.

Jasming Yaying Went, left, completes an activity in her English class identifying the ways hepatitis C can be transmitted.

At some of Lo’s workshops, nurses on-site will swab the cheeks of participants who want to see if their body is producing hepatitis C antibodies. If they test positive, a follow-up can determine whether they have an active infection and need treatment.

At the ESL class, though, participants were given a pamphlet in English and Chinese with a code they could use online to sign up for a blood test at several labs in Metro Vancouver without a referral from a doctor.

After the workshop, Weng thinks she will get tested because “it’s very important.”

Another student, Jolly Zhu, said the session cleared up some misconceptions she had about the virus that attacks the liver.

“Before this class I always thought hepatitis C can't be cured—forever,” she said. “I thought it's a terrible disease.”

As for getting tested, she said maybe.

So far, Dr. Ramji has also partnered with the Progressive Intercultural Community Centre in addition to SUCCESS. The goal is to connect immigrants who could potentially be infected to B.C.’s health care system.

It’s one of several similar projects going on around the country that all received a grant from Gilead Sciences, an antiviral manufacturer, to help link certain groups to hepatitis C care.

Two programs in Ottawa and one in Calgary look at how to connect people in prison and those recently released with hepatitis C treatment. Being incarcerated puts one at greater risk of the virus in part because of a lack of clean needle programs for injecting drug users.

More studies in Toronto and Quebec look at enhancing hepatitis C treatment for people who frequent supervised drug consumption sites.

Others look at how effective community-based screening programs are in First Nations in Saskatchewan and Quebec.

The WHO wants to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health threat by 2030 as part of its sustainable development goals. Its vision of doing that means reducing new infections by 90 per cent and mortality by 65 within the next 12 years.

Viral hepatitis is also a focus of the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, with the centre opening a new facility with facilities dedicated to hepatitis C research in 2017.

Source: Global Burden of Hepatitis C: Considerations for Healthcare Providers in the United States. Hepatitis C is considered endemic in countires with greater than two per cent prevalance.