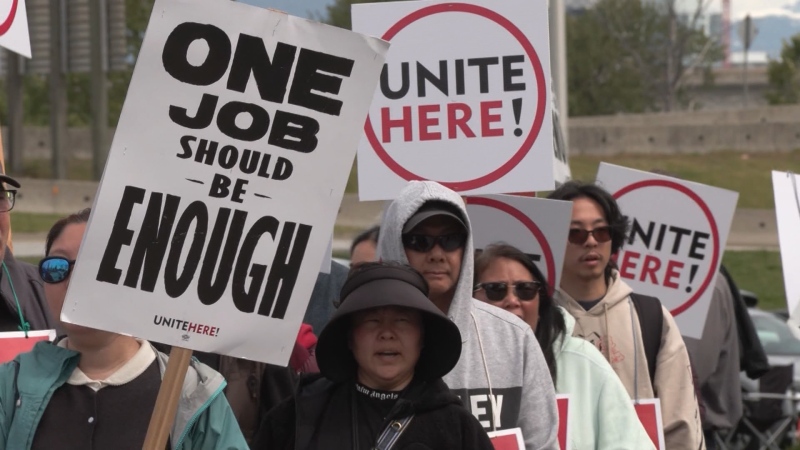

No one likes to be nickel-and-dimed.

That's why those who speak on behalf of consumers who pay for plastic bags and those who study the environment those fees are purportedly designed to protect are calling for greater transparency from retailers.

"If it is going to the environment, then let us see the figures on it," Consumers' Association of Canada president Bruce Cran told CTV News.

Plastic and paper bags used to be a standard part of customer service. Nowadays, consumers pay five cents per bag at many businesses. The move to paid bags was initially billed as an environmental initiative that would at once encourage people to purchase reusable bags and allow companies to invest in green causes with the money collected from sold bags.

But Cran has his doubts as to how well that system is working

"They don't provide any figures or profit margins or anything else on those bags," he said. "I'm led to believe that a paper bag that we pay five cents for they obtain for under one cent. If they want to argue about it, let them tell us what they pay."

Retailers wouldn't tell CTV how much each bag costs them or how many they sell, but calculations done based on the information available suggest some big bucks are at stake.

The Plastic Association of Canada suggests each bag costs 2.5 cents at most.

CTV took to the streets of Metro Vancouver, visiting different stores in different neighborhoods at different times of day to get a sense of just how many bags are being sold.

The average came out to 200 an hour.

When multiplied by the number of stores known to charge for bags across the country and the number of hours they're open, the small contribution amounted to a whopping $63 million a year Canada-wide.

While not a scientific calculation, Cran said the number isn't implausible.

"I think there's a serious profit being made here… I'm sure it's in the tens of millions probably for most of these companies," he said. "I think it's ridiculous they're charging us. What are we going to do, carry the stuff out in our mouths or something?"

In a statement, Loblaws, which owns Superstore and Shoppers Drug Mart, said in part that it "reinvests partial proceeds… to help promote environmental sustainability."

Those contributions include $1 million to the World Wildlife Fund, the company said.

Save-On-Foods, another major grocer, said it's "not charging bags to make a profit" and reinvests in Ocean Wise.

Yet retailers seem hesitant offer customers an incentive for bringing their own bags instead of charging them a penalty for not doing so.

An environmental sociologists at the University of British Columbia agrees that penalties are more likely to get people to change their behaviour than rewards, but said the practice of charging for bags puts too much of the responsibility on shoppers.

"What I don't think is fair is putting more and more of the burden on consumers to protect the environment. There's a lot of things that grocery stores could do. They could use plastics that are easier to biodegrade, they could look into different materials for helping people get their groceries from the store out to wherever they're going," Emily Huddart Kennedy told CTV.

"It feels like you're putting the onus or the burden on the least powerful actor in the system, the consumer, rather than putting the burden on this very powerful actor, the grocery store."

According to Plastic Oceans Foundation Canada, Canadians use nearly 3 billion plastic bags each year, or about 200 per capita.

The environmental impact of that plastic consumption has led cities such as Montreal and Victoria to ban plastic bags.

Business like Ikea have committed to significantly curb or eliminate their plastic usage in the coming years.

But alternatives to plastic bags are not necessarily more environmentally friendly, Huddart said.

The production of reusable cloth bags, for instance, produces fewer greenhouse gases, but consumes much more water that plastic bags. And if shoppers reuse their plastics multiple times, it can in some cases be the greener option of the two.

"Consumers are sort frozen," Huddart Kennedy said. "We don't actually have a great solution for how to transport things. Cloth bags aren't perfect. Plastic bags aren't perfect. Paper bags aren't perfect."

With files from CTV Vancouver's St. John Alexander