VANCOUVER -- Eileen Mohan knows what it’s like to lose someone to gang violence.

Her only son, Christopher Mohan, was shot and killed when he was 22-years-old, one of six people murdered, in the spree of killings dubbed the Surrey Six.

Mohan and another man, Ed Schellenberg, were both innocent victims.

“It’s been 14 years, but for me, it’s like yesterday,” Mohan said, “holding my own dead son in my arms.”

Mohan has been watching the escalation in gang-related gun violence across the Lower Mainland, including high-profile public assassinations, with horror and the sense that history is repeating itself.

She told CTV News Vancouver a new generation of gangsters appears to have emboldened itself and she is not the least bit surprised.

“If we don’t have a message from the court system to deter gang warfare, this is what is going to continue to happen,” Mohan said.

And she speaks from personal experience.

The two gangsters found guilty of her son’s 2007 murder have their convictions on hold, while they apply for a stay in proceedings based on an abuse of process.

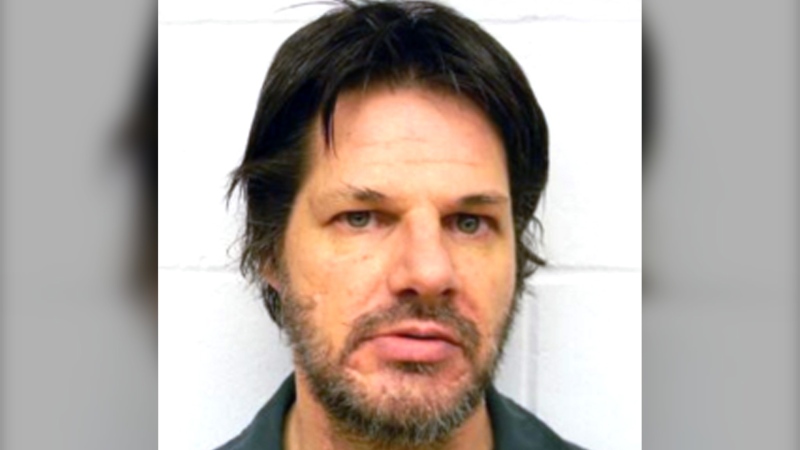

Red Scorpion gang leader Jamie Bacon, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit the murder of one of the victims. With credit for time served, Bacon will spend a total of five years and seven months behind bars.

Mohan said she gives the courts a “failing grade” when it comes to deterring gangsters and would-be killers.

“The message that comes out from the court system is very weak,” she said. “Look at where my case is at the moment. How many sweetheart deals have been cut through the courts?”

Mohan added she’s had conversations with the provincial attorney general and solicitor general, and has written to the federal justice minister, but on the subject of the courts, they’ve all been “silent.”

In a statement, Attorney General David Eby told CTV News in part: “My heart goes out to Eileen Mohan on the tragic loss of her son, and all that she’s gone through since this tragic incident occurred. Our government works hard to ensure timely access to justice so that justice is served.”

Eby went on to write the B.C Prosecution Service has been working to reduce systemic delays in the court to meet timelines established by the Supreme Court of Canada, and has committed to increase the number of sheriffs and court administrative staff.

In 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada in R v. Jordan established how quickly a trial must be heard, creating additional challenges for investigators and Crown counsel surrounding timelines when it comes to making arrests and laying charges.

“However,” Eby wrote, “the federal government also needs to fill vacancies on the BC Supreme Court, which hears the more serious cases. Victims of crime deserve and should expect nothing less.”

Eby did not directly answer questions about how Canada’s criminal code could or should be reformed to further deter takedowns by gangsters in public places that put innocent people at risk.

Mohan praised the actions of police and investigators in their efforts to combat the latest surge in gun violence.

But she added there is a need for more political will from elected leaders across Canada to work to reform the overall justice system. If they don’t, she fears a new generation of gangsters, willing to take risks and endanger the public, will continue to rise up.

“You can walk to the doorstep of my home, steal my sons innocent life,” Mohan said, “and then, the courts will protect you.”