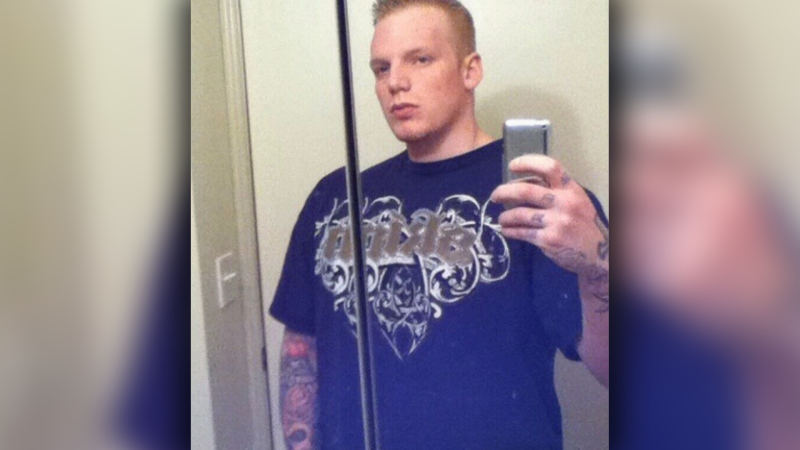

VANCOUVER -- Amir Javid didn't climb into the dangerous world of Vancouver's street gangs to escape a rough childhood. He wasn't living in poverty, wasn't raised around crime and drugs.

But a few years after his family immigrated from Iran, at age 15 or 16, Javid helped form one of the gangs that is now waging a bloody war in the Vancouver area, with nearly 40 shootings that have left more than a dozen people dead.

"We simply came together because we had a common fear," says Javid, 26, who left the gang life a few years ago and now does outreach work targeting current and potential gang members.

"Our common fear was, we were a minority and we had to band together as a minority to sort of have some sort of standing."

Raised in a Christian home in Richmond, B.C., Javid didn't have the traditional warning signs that lead some to slip into the gang lifestyle: Poverty, a broken home, addiction, mental illness.

And he says there is an increasing number of gang members coming not from the squalor of poverty, but rather well-adjusted and sometimes affluent homes.

"What you're seeing is a spike in affluent families, good solid families," says Javid.

"The gangs are giving these kids the opportunity to get excited about something. These kids have everything in their life, they have a good family, except they don't have that thing that makes them feel worthwhile and appreciated."

What Javid is describing is still the minority of cases, says author Michael Chettleburgh, but there's an increasing number of gangsters in the Vancouver area, more so than anywhere else, who seem to have no obvious reason to enter the dangerous world of crime.

"They have access to money, they have two parents at home, they live in a nice house -- they don't have some of those classic risk factors that we get with some of those other kids," says Chettleburgh, author of "Young Thugs: Inside the Dangerous World of Canadian Street Gangs."

"I think it's happening more so in your part of the country. If I was to assemble a random sample of gangsters in Toronto, we're not going to have a lot of wealthy, rich boys who are joining gangs."

Chettleburgh says there are about 2,000 gang members in the Lower Mainland, and about three-quarters of them likely have the traditional risk factors.

However, he says it's more difficult to explain why the rest end up in gangs.

"They may not be joining because of socio-economic drivers, but for them it's mostly just about creating a new identity for themselves," he says. "It's about a sense of belonging and creating a new persona, and those are powerful pulls for everybody, irrespective of your background."

While it's not limited to any particular cultural group, Chettleburgh says the phenomenon appears to be more common among first- and second-generation Canadians.

For example, a federal government committee, largely made up of members of B.C.'s South Asian community, released a report in 2006 that specifically noted that some Indo-Canadian gang members were coming from "highly affluent families."

Chettleburgh says there may be a number of reasons.

"There's a culture clash between parents, the elders wanting to embrace a traditional way and the kids embracing, full-bore, the North American lifestyle," he says.

"So you think about it, `Yes, I've got access to daddy's Lexus and I live in a million-dollar house, but man, I can make a half a million dollars cash by doing this.' So it becomes a really powerful elixir."

If they're not well-off to begin with, the money and power that comes with the gang lifestyle is a powerful lure, says the head of B.C.'s Integrated Gang Task Force.

"If they're 20 to 35 years old and they've never held a job and they can afford $300 jeans and $300 T-shirts and they live on an acreage that they're renting for $5,000 a month, they're probably not average citizens," says Supt. Dan Malo.

"If they have that much money to throw around, chances are they're in the drug trade."

Police and community groups have tried various ways to persuade young people, whatever their situation, to avoid getting involved in street gangs, from edgy TV ads to classroom presentations.

But Malo says it seems to be falling on deaf ears.

"We've got to show to teenagers that the average lifespan of a gang member is 26 years old, and that doesn't seem to stick," says Malo.

"The light's not coming on."

As a former gang member himself, Javid thinks he has part of the solution.

Through the organization he founded, Real World Truth, he visits schools and talks to students of all backgrounds about the personal costs of joining the gang life. He also approaches current gangsters and offers to help them leave their gangs and restart their lives.

"They're not going to listen to a cop in the classroom, you know?" says Javid.

"They're going to get engaged from somebody who's been there and can say, `I know where you're at, I know the reasons why you want to get involved, so let me tell you what involvement is."'