Hornby Island, B.C. - Visitor brochures for Hornby Island boast of its creative residents, serenity, and security.

It is considered a "jewel" of the Gulf Islands.

But this paradise was shattered on a cold, drizzly morning last November when the body of Tempest Grace Gale -- a popular artist, poet and musician -- was found floating in the marina where she lived with her parents and boyfriend.

Two and a half months later, the homicide -- Hornby's first -- remains unsolved, and the island's 1,000 residents are still reeling.

Speaking publicly for the first time, parents Mike and Jazzmyre Gale and boyfriend Steph Desjardins -- their faces still pale with anguish -- told ctvbc.ca they have not been able to return to the marina.

They have opted instead for the comfort and security of friends' homes on the island.

The memories are too fresh, they say. And the killer is still out there.

At the same time, they insist they are not fearful. To admit fear, they said, would only empower the killer.

"To live in fear is not living," Desjardins said.

Meanwhile, Hornby's residents -- who turned out by the hundreds for Gale's funeral -- wrestle with this question: How does a community whose nearest police detachment is two ferry rides away and whose officers are on the island full-time only during the summer ensure the safety of its residents?

The debate has been simmering at community gathering spots and in Hornby's local newsletter, The First Edition.

One anonymous letter writer wrote that Hornby had become too welcoming of strangers with undesirable traits.

"We have learnt long ago that Hornby will not interfere with, nor limit, any behavior: they would rather shoot the messenger," the person wrote.

"I lay part of the blame squarely at the feet of the community on this one."

Many residents took offense.

"Since you think this community is composed of dwellers in cloud-cuckoo land, who do not have responsibility or accountability, I suggest you unlock your doors and your mind and get involved in the huge network of volunteers who make those qualities live here -- everyday," 35-year resident Carole Chambers wrote in a response.

Some residents are advocating the creation of a network of local citizens who can be called upon to respond if someone needs help.

But that raises other questions, namely: How do you ensure that it doesn't turn into a vigilante group?

Family settles

Hornby Island's main road starts at the ferry terminal and ends at picturesque Ford's Cove.

It's at this marina that the Gale family settled more than 10 years ago after living in northern California and Oregon.

It wasn't just the physical beauty of the place that attracted them, it was the kindness of the people, Jazzmyre Gale said.

Mike and Jazzmyre Gale became fixtures of the island, working as gardeners and groundskeepers.

Their daughter, Tempest, went through a phase during her teens when she dressed all in black and insulated herself.

Then, family and friends say, she blossomed into a confident, outgoing young adult, whose interests showed no boundaries: native spirituality, the environment, guitar and banjo playing, poetry, soap-making, doll-making, stilt-walking, unicycle riding.

Music bonded the Gale clan. Even after she got her own boat, Tempest Gale frequently joined her parents on theirs for breakfast and then they would jam on the deck.

She also found love.

Steph Desjardins, an Ontario native, moved to the area six years ago after living in Lake Louise, Alta.

Gale taught him about spirituality and nature.

"She lived the way we should all live. She felt everyone had something to teach her and she had something to teach them," he said.

She also taught him to appreciate the simple things in life.

One of his favourite memories is sitting on the deck of his girlfriend's boat under the moonlight last summer. She strummed the banjo. There was just a hint of a breeze.

It was the perfect night.

The drifter

Hornby residents acknowledge that in addition to attracting retirees and ex-urbanites, their island draws its fair share of folks who don't fit into mainstream society -- "the crazies."

For many, Hornby is a destination. For others, it's the "end of the road," residents say.

Usually, everyone co-exists peacefully.

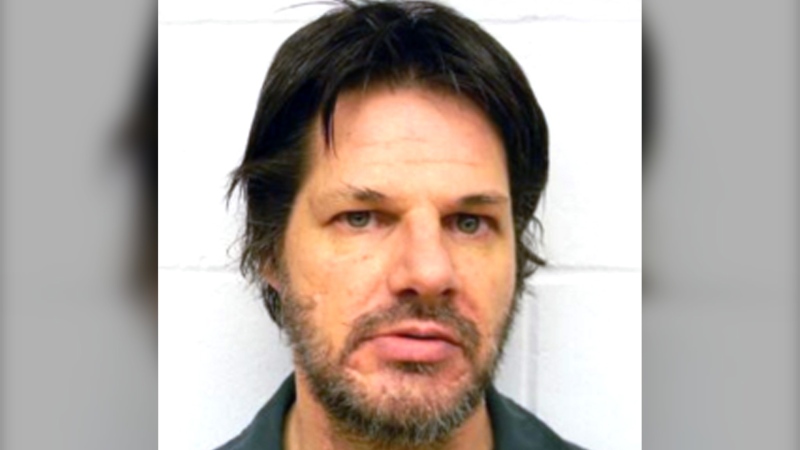

But one middle-aged man who took up residence at Ford's Cove last summer next to Mike and Jazzmyre Gale's boat began causing problems.

For reasons the Gales say are unknown to them, the man, who had been raised on the island by foster parents, began taunting them, even tearing by them in his truck as they walked or rode their bikes on the road.

On Nov. 17, Jazzmyre Gale had had enough and approached the harbour manager to complain.

She said she was creeped out by the guy, harbour manager Una Keziere recalled.

Mike and Jazzmyre Gale spent that night at a friend's house.

Keziere now says that she, too, had a bad vibe about the man since her first conversation with him that summer.

But she said her hands were tied. She couldn't just cut him loose.

Then at about 7 p.m. that night, the man called her.

She said he told her that he was fed up with the place and would be on the first ferry off the island the next day.

He said he would sell the boat, give it to his foster parents or return it to the owner.

Problem solved, Keziere thought.

"No! No! No!"

Tempest Gale had spent much of that day with a friend. They were working on a project to preserve the hide of a deer that had been hit by a car.

Desjardins, meanwhile, had dinner with Gale's parents at the house where they were spending the night. After dinner, he returned to his boat.

It was about 8 p.m.

Gale wasn't there, which wasn't out of the ordinary since she had a habit of getting caught up in the things she was working on.

Desjardins went to bed.

About 5 a.m. the next morning, Desjardins woke up to find that Gale had still not returned.

Using a flashlight, he went searching for her. That's when he spotted some toast and a cup of tea lying on the dock.

Concerned, he called Colleen Work, with whom Gale's parents had been staying that night.

Then he called 911.

A friend came down to the dock to help Desjardins look for Gale.

About a half-hour to 45 minutes later, they spotted her in the water.

Gale was dressed in heavy clothes.

Her laptop was also recovered from the water.

Gale's family later surmised that she had probably been heading up to the local store the night before because it had Wi-Fi access.

"Everything was surreal to me. I was begging to wake up," Desjardins recalled.

He said he called his mother.

"That's when it became real."

Desjardins' friend made the second call to 911.

Gale's parents arrived a short time later.

Marina owner Matthew Fredbeck was inside his house at about 7:45 a.m. when he said he heard a man screaming at the top of his lungs.

"No! No! No!" he recalled the man yell. "My daughter!"

A ‘person of interest'

Some residents complain that the police can be slow to respond.

RCMP Insp. Tom Gray of the Comox Valley detachment acknowledges that unless there is an imminent threat to life and limb, officers can't respond immediately to every call.

That morning, they wasted no time.

A police helicopter landed on a narrow road at the marina. A bevy of police cars crossed by ferry.

Word of Tempest Gale's death spread fast.

On Hornby, everyone knows each other's business, residents say. Thirty-five year resident Carole Chambers calls it the "bush telegraph."

Residents quickly fingered the man who had been harassing the Gale family.

In a press release later that day, police said they had brought in a "person of interest" for questioning but did not identify that person.

That person was released the following morning.

Two days later, police officially declared the case a homicide.

Since then, police have said very little.

In an interview, Insp. Gray admitted that the case will be a difficult one to solve.

But he said it is far from being a cold case.

In a letter to the community published last month in the Island Grapevine newsletter, Gray asked for patience.

"This is a difficult investigation and considerable patience is necessary to complete the task that is before us," he wrote. "Investigational activities continue and I am unable to provide an estimate at this time when more positive information can be shared with the community."

The Gale family says they feel strong they know who the killer is. While they are frustrated no arrests have been made, they say they understand that investigations take time.

The man who had allegedly been harassing the Gale family has since left the island.

But a composite sketch of him remains tacked on a board outside the Ford's Cove store.

"Ford's Cove Person of Interest," it says.

Gripped by grief and fear

On a rain-soaked day in late November, hundreds turned out to attend Tempest Gale's funeral.

Her parents' faces were painted like death masks. They also wore native masks on the backs of their heads for protection.

Desjardins and a friend had spent hours carving Gale's coffin out of maple wood. Friends painted a sailboat on the cover and made handles out of bones. Gale's grandfather added intricate knotwork.

To the beat of a drum, six people carried the coffin on cedar poles from the local park to the nearby cemetery.

A stretch of Hornby's main road shut down to allow the procession to make the journey.

The service was imbued with First Nations, Buddhist, pagan and other influences.

Each resident took turns shoveling dirt on the grave site.

Carole Chambers, who attended the burial, described the experience as deeply profound – almost "primal."

The grave site was decorated with Gale's black boots, feathers, shells, bones, flowers and other items special to her.

At the same time the community grieved, some residents were gripped by fear. Half the population is over 65.

A sign went up on the bulletin board outside the local co-op store: "If you are in need in the face of the recent events, don't remain afraid or alone … a network of helpful people are here to help."

Preventing future violence

Some residents admit to feeling a sense of guilt in the weeks that followed.

Had they known that someone had been harassing the family, perhaps they could have intervened, they say.

The community will definitely be more vigilant and watchful, they add.

Eamon O'Brien, a friend of the Gale family and Hornby resident for 20 years, says he is in the midst of developing a network of residents who can jump in at a moment's notice to respond to domestic violence calls or other emergencies when police might not be able to respond.

It's not unheard of, he said, for groups of people to confront someone who might be hostile or creating a disturbance and have that person escorted off the island.

The tricky part is how do you ensure that it doesn't turn from a group of citizens helping citizens into a vigilante group?

You have to ensure there aren't "hot heads," Carole Chambers said.

Most residents seem to agree that beefing up police presence on the island is not the answer.

Outside of the summer, it's usually very quiet, residents say.

Besides, many residents come to the island to escape the trappings of urban life.

"We're glad when they're here, we're glad when they're not here," said 20-year resident Roy Slack of the police.

The future

The Gale family is slowly trying to get back into a routine.

Mike and Jazzmyre Gale have been doing a bit of gardening. They'll have the occasional jam session.

They're working on developing a zero-violence initiative for Hornby Island.

They also plan to publish their daughter's poetry and get her music out.

Steph Desjardins says he spends most of his days indoors, preferring to stay close to the Gales.

He says he can't get over the feeling that he failed his girlfriend.

"As a man who just lost my partner, I wish I could've been there," he says.

The family says they aren't certain when they'll be ready to move back to their boats in Ford's Cove.

They say they are planning to move to another friend's house soon.