VANCOUVER -- As Lily Speed-Namox watched news about the Minneapolis man whose death in police custody ignited a massive anti-racism movement across the United States, she says it reminded her of her father.

RCMP have said Dale Culver, 35, appeared to have trouble breathing before he died in police custody in 2017 in Prince George, B.C.

“My little brother was four and my sister was six months old when it happened. She will never get to know her father,” said Speed-Namox, now 17.

While charges were laid within days against a Minneapolis officer in George Floyd's death, no charges have been laid three years after Culver's death.

The Independent Investigations Office of B.C. announced last week that it forwarded a report to the BC Prosecution Service for consideration of charges against five Mounties involved.

Chief Civilian Director Ronald J. MacDonald found reasonable grounds to believe that two officers may have committed offences in relation to use of force in the arrest and three others may have obstructed justice, the watchdog agency says in a bulletin posted on its website.

The allegations have not been proven in court.

The RCMP said they are co-operating with investigators and will continue to support the officers in the next phase of the process.

“The impact this announcement may have on not only the family of the deceased but also on our employees, cannot be understated. Our thoughts remain with the family during this difficult time,” Cpl. Chris Manseau said in a statement.

The officers involved continue to patrol the same community of 75,000, the RCMP said.

Culver, an Indigenous man from the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en Nations, was arrested in Prince George, B.C., on July 18, 2017.

An RCMP release from the time says police received a report about a man casing vehicles and found a suspect who tried to flee on a bicycle.

There was allegedly a struggle when police tried to take the man into custody, other officers were called, and pepper spray was used. Officers noticed the man appeared to have trouble breathing and called for medical assistance. He collapsed immediately after being taken out of the police vehicle and died soon after, police say.

The BC Civil Liberties Association alleged in a 2018 complaint to the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP that the association had “learned of troubling allegations that RCMP members told witnesses to delete cellphone video that they had taken.”

“This is a key development for his family and the Wet'suwet'en Nation's pursuit of justice for Dale,” the association tweeted after news of the watchdog agency's report was posted May 29.

The association didn't name any of the witnesses who made unproven allegations in its 2019 complaint.

Speed-Namox said when her mother woke her up in the middle of the night to tell her that her father had died, she also asked Speed-Namox to avoid social media because video of the arrest was circulating.

In an interview, MacDonald acknowledged the investigation process has been slow. The IIO was responsible for some delays and there were other systemic lags, including autopsy results that took a year, he said.

Investigators learned new information when they met again with family and community members after initially announcing plans to refer the case to Crown in July 2019.

“A couple of things flowed from that. One was that some additional evidence or witness evidence was made available to us,” he said.

The number of officers facing possible charges rose to five from four as a result, MacDonald said.

He said Floyd and Culver's cases differ in “many, many different ways,” although he could not discuss specific details about Culver's case.

Rather than asking why the Canadian process takes so long, he said he wonders why the American system is so quick.

“I would suggest that a good, thorough, proper, fair, objective investigation, such as even in the George Floyd case, ought to have taken longer than just a few days.”

He noted Canada and the United States have different legal frameworks.

The Supreme Court of Canada has set a limit of 18 months between the laying of charges and the actual or anticipated end of a trial in provincial court. The “Jordan rule” gives investigators incentive to gather as much evidence as possible before charges are laid, and the clock starts ticking.

BC Prosecution Service spokesman Dan McLaughlin said that in complex cases, it may take weeks or months before a decision is reached about whether to approve charges.

Crown prosecutors must weigh if there's enough evidence to support a substantial likelihood of conviction and whether the public interest requires a prosecution, he said.

“We do not have a timeline for the completion of the assessment process in this case,” McLaughlin said in an email.

Debbie Pierre, Culver's cousin and next of kin, said she has been happy with the Independent Investigations Office, which has kept the family up to date throughout the process.

“We're trusting in the process and hoping that justice will prevail here, and changes will happen,” she said.

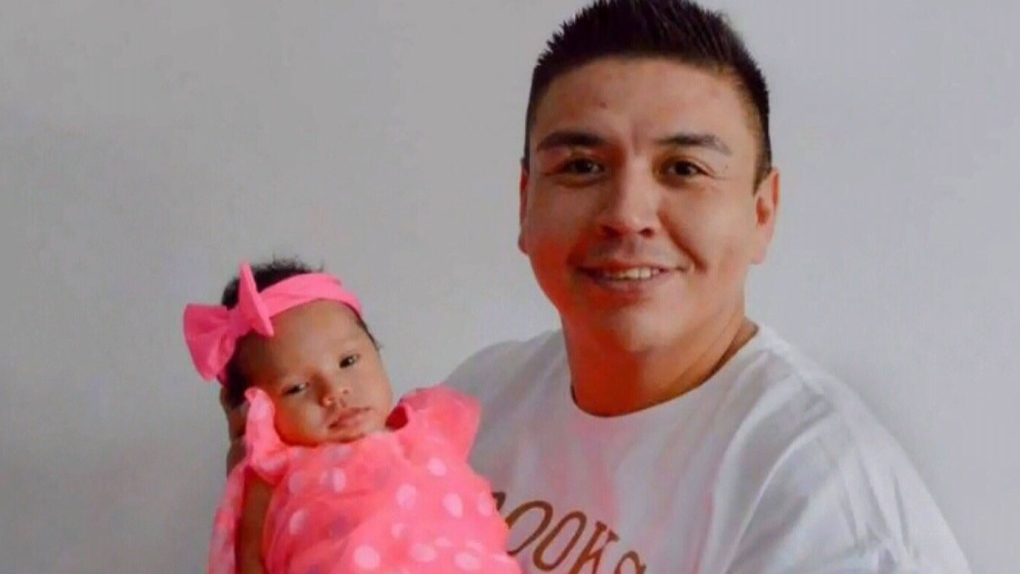

The family doesn't want Culver, whom they remember for his wide smile and for doing things to make others happy, to become a statistic, Pierre said.

A history of discrimination has created a fraught relationship between police and Indigenous people in Canada. The family wants to see significant changes to police training, and while cultural sensitivity training is a good step, it hasn't been enough, Pierre said.

Speed-Namox said she wants to see the relationship between police and racialized communities improve.

“There's been some kind of trust between the people and the RCMP that has been broken and we need to be able to find some way that we can mend that,” she said.

Tracy Speed, Speed-Namox's mother, said she's afraid knowing the same officers are patrolling the community when they could be facing charges.

“As Lily's mother, if anything ever happened, she's walking down the street with her buddies or whatever, it's just unnerving to know they could run her name, find out who she is and I don't know. There's not a lot faith in the RCMP in Prince George right now, at least from us and our family. It's very unnerving.”

A 14-year-old cousin of Culver's recently ran home in fear when he saw a police car coming toward him, she said.

“It's crazy that we have a fear of the people who are supposed to serve and protect us.”

Family members plan to attend a peaceful anti-racism protest Friday in Prince George, B.C.

With files from Rob Drinkwater in Edmonton

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 4, 2020.