Some B.C. police dog units bite and injure people as much as 10 times more than dog units that use a less aggressive style of training, a CTV News investigation has found.

That’s an indication that dogs following a “bite and hold” method – meaning that every time they are released, they will bite a subject – are biting subjects when they don’t deserve it, according to a former police dog handler.

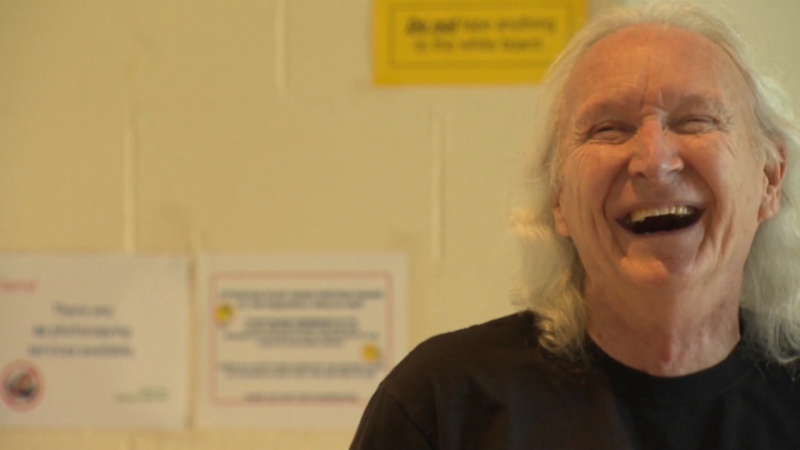

“Why should people get bit if they don’t have to get bit,” said Doug Deacon, who spent years training police dogs in B.C.

“Does a police officer have a right to go in and punch someone all the time? No. Should a dog be biting all the time? No,” he said.

CTV News looked at statistics from municipal police detachments, as well as records disclosed under Access to Information rules from the RCMP.

They showed that many police dogs are used to apprehend subjects, some with knives, guns or other weapons, or people who were threatening others.

However other times dogs were used to attack people who were hiding behind office equipment, under staircases, or using marijuana. In six cases, the dogs bit innocent people by accident.

In one accidental bite, a Maple Ridge caterer, Bill Evanow, was a Good Samaritan trying to help police catch a thief in March 2011. He was mistaken for the thief by the dog, which bit his leg, taking out a chunk of muscle and causing permanent damage.

In 56 cases in 2010 and 2011, RCMP dogs bit someone under 18, according to the records. The two youngest people bit were 13-year-old boy whom police allege was operating a dangerous motor vehicle, and a 13-year-old girl whom police say was actively resisting arrest.

RCMP Staff Sergeant Dave Willson said that the “bite and hold” training protects officers and dogs from dangerous subjects. At the end of the day, the force trusts the decisions of the dog handlers to engage the dogs in tough situations, he said.

“The deploying of the dog to apprehend someone is the decision of the handler. It’s not the dog deciding to bite someone,” he said.

In comparison, the training method used by police in Saanich, New Westminster, and Delta police is known as “bark and hold.” In that method, the dog approaches a subject and barks, unless it detects motion or is ordered to bite by the handler.

Those three detachments had between zero and three bites each year, the records show.

In comparison, Vancouver, which polices a higher population, and the RCMP, which polices a still higher population in BC, injured 88 people and 222 people in 2011 respectively.

When the differences in population are taken into account, RCMP dogs bit about 5 times more often per capita, and VPD dogs bit almost 10 times more per capita, the records show.

Pivot Legal Society’s Doug King said that his research showed that police dogs accounted for half of all reported injuries by police in B.C.

“We know that someone is hospitalized every two days by a police dog,” he said, adding that he believes the provincial government should demand changes.

Neither Vancouver Police nor the RCMP could point to any studies on police dog bites in Canada. The Vancouver Police recommended the work of Florida-based criminologist Charles Mesloh, who found that “bark and hold” dogs bit more often for each time they were deployed in Florida.

Mesloh told CTV News there were many differences in the way that police dogs were used in the two countries that made comparing the data difficult.

However, he said that in Florida he would recommend the “bite and hold” system because it afforded more protection for police and appeared to result in fewer injuries.

Deacon said the difference between countries could be explained by weaknesses in control by police dog handlers in local police forces. Some handlers are excellent, he said, but others do not control their dogs well.

“I think that if you use the basic foundations from good, sound dog training such as they use in sport, that would really help and enhance police dog control and it would reduce the number of bites and lawsuits,” he said.